Tributes

“Of Looking, and Looking”: On Mary Oliver

Introduction by Alice Quinn

I—and we at the Poetry Society of America—had the greatest respect and fondness for Mary Oliver, our 1970 Shelley Memorial Award winner, both for her poetry and her way of being in the world.

I had the honor of introducing Mary twice at the 92nd Street Y, the second time only a short while after the death in 2005 of her partner Molly Malone Cook who had one of the most memorable and adorable chuckles I have ever heard. She was utterly devoted to Mary as Mary was to her, ever since they met sometime in the late 1950s at Steepletop, Edna St. Vincent Millay's home in Austerlitz, New York. As a point of information, St.Vincent was the name of the hospital where Millay was born, and the AIDS Memorial designed by Jenny Holzer and located across from the former hospital's site (at Twelfth Street and Greenwich Avenue in New York) features much of the text of "Song of Myself" by Walt Whitman, one of Mary Oliver's touchstone poets.

Mary recently sent me a present twice as the first time it was mysteriously returned to her. ("Surely the tea strainer wasn't arguing about living with you!" she wrote.) It is Elizabeth Bishop's tea strainer from Brazil, the land of cafezinho. It's clear that Bishop dictated the construction of it, and this marvel is one of the most treasured of all the things I feel steward of while on this earth. It's even more marvelous to me because Mary couldn't recall how she came into possession of it. Passing it on was the paramount obligation.

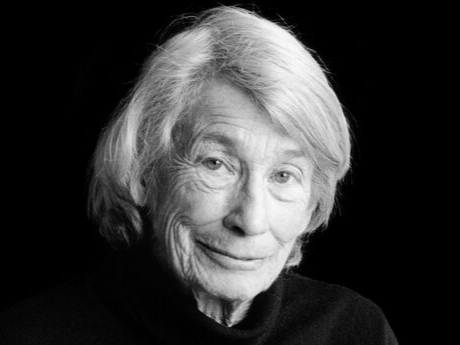

By way of homage, we are presenting a beautiful tribute to Mary written by Jason Myers, a former (and devoted) student of hers at Bennington who is pictured here with the baby he alludes to in his piece.

"Of Looking, and Looking": On Mary Oliver

All morning the rain has been delivering its packages to the grass, the wildflowers that in a month or two will turn the fields and roadsides of central Texas into a carnival of color. Yesterday the sun rinsed everything in a wash of wonder. When I learned that Mary had died I was sitting in a pediatrician's office, holding my week-old son in my arms. Tears stung my eyes, but I held back from weeping, embarrassed of strangers. Weeks before, when we still did not know if his mother would follow through with her adoption plan, my wife and I attended the baptism of several children at our church. Just as the congregation launched into the stately melody of "Take Me to the Water," my work phone rang. Hospice chaplain, I was summoned to the bedside of a dying man. Doors open, doors close. A little light gets in.

In her poem "White Owl Flies Into and Out of the Field" Oliver proposes, from her observations of the predatory bird, 'that we are instantly weary' at the moment of death, 'of looking, and looking, and shut our eyes,/not without astonishment,/and let ourselves be carried.' As in many of her poems, Revelation is closely related to time spent marveling the ravishing particulars of 'each mortal thing' and trying to capture, with the perception of language, what shines or sighs out of every shell, flower, feather, stranger and friend. "They're all just description," Elizabeth Bishop remarked of her verse with characteristic sly modesty. Oliver's line about looking is an obvious lift from Bishop's poem "Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance," the last lines of which read:

Why couldn't we have seen

this old Nativity while we were at it?

–the dark ajar, the rocks breaking with light,

an undisturbed, unbreathing flame,

colorless, sparkless, freely fed on straw,

and, lulled within, a family with pets,

–and looked and looked our infant sight away.

The poet lodges between infancy and ecstasy, seeking after knowledge yet wanting a reprieve from the burdens of history. Bishop was an obvious forerunner to Oliver, a woman of expert craft and immense linguistic dexterity in a literary tradition dominated by men, a lesbian who was unashamed of her love life while also reticent, guarding her privacy. They both shied away from the poem-as-confessional, Bishop adopting the tone of an ever-resourceful travel guide, as comfortable "At the Fishhouses" as in museums, while Oliver wrote as a mystic in the woods, taking her cues as much from Rumi and Basho as any European-American model. Each has been criticized for failing to engage political matters in their poems, though Bishop's "Roosters" is as fierce as any anti-war poem I know in American letters, and Oliver in "Of Empire," charts the deleterious effects of capitalism and consumerism.

And they will say that this structure

was held together politically, which it was, and

they will say also that our politics was no more

than an apparatus to accommodate the feelings of

the heart, and that the heart, in those days,

was small, and hard, and full of meanness.

Oliver bore witness to the feelings of the heart, titling poems simply "Rage" and "A Bitterness." If she often portrayed the gladness, the luxuriant joys of keeping company with woods and bears and ponds and swans, roses and poppies and lilies and berries, she also anatomized fear, desire, shame, and disgust. Particularly in poems like "Singapore" and "Indonesia" she examines the perils and abominations of class and racial differences. Both of these poems inhabit the queasy feelings that attend recognition of privilege.

In the former, the speaker encounters a woman cleaning an airport bathroom and confides, 'a darkness was ripped from my eyes.' The labor that often goes unnoticed or is dismissed with condescension receives the same rich attention Oliver paid to owls and pine trees. Still, she captures the difficulty people have in noticing and naming difference.

Pain, and the desire to turn away from pain, are the cornerstones of all wisdom literature, and like the greatest of her recent peers, among whom I would name Li-Young Lee, Lucille Clifton, and Galway Kinnell, Oliver was at her best when she could hold joy and the thieves of joy in the same hour, the same meditation. The cleaning woman of "Singapore" and the tea pickers of "Indonesia" elicit the same holy and vivid regard as blackberries and wild geese. If Oliver's poetry was all bouquets and tame deer, as some have misinterpreted it to be, it would not carry the authority, the ability to astonish as these lines from "Indonesia":

Don't ask if it was the fire of honey

or the fire of death, don't ask

if we were determined to live, at last,

with merciful hearts.

Or these from "Goldenrods":

Are not the difficult labors of our lives

full of dark hours?

And what has consciousness come to anyway, so far,

that is better than these light-filled bodies?

Elizabeth Bishop posed "Questions of Travel" and Oliver returns again and again to the question as a model for humility, reverie, reverence. In "Some Questions You Might Ask" she remarks that 'The face of the moose is as sad/as the face of Jesus.' Her moose is different from Bishop's renowned she-moose, yet also a source of wonder, a portal from the routines of the rational into a space that, if not sublime, allows for a quality of consciousness open to the varieties of religious experience. As the title of her final volume, Devotions, indicates, Oliver was essentially a religious poet, pondering the nature of the soul, speculating on the divinity immanent and transcendent in the fecund, devouring, daffodil-dancing earth, "Making the House Ready for the Lord," a poem which ends:

you will, when I speak to the fox,

the sparrow, the lost dog, the shivering sea-goose, know

that really I am speaking to you whenever I say,

as I do all morning and afternoon: Come in, Come in.

Days have passed since I started to write this. Time evaporates when you live with a baby, just as it does when you step into the temple of nature. It has been almost twenty years since I knew Mary as my teacher at Bennington College. Yet that time with her is as accessible to me now as what happened yesterday. I remember a conversation we had once in her office, where we often discussed meter and imagery, Hopkins and Dickinson, Bob Dylan and Edgar Allan Poe. She was describing the qualities of conservation and the complex role of the witness given our various ecological crises. Just as we question the complicity of photojournalists in war (and those of us who want to see their photographs), Mary mused that sometimes we have to stay out of the woods to preserve them.

I recalled this conversation as I reread her poem "October," which ends:

One morning

the fox came down the hill, glittering, and confident,

and didn't see me - and I thought:

so this is the world.

I'm not in it.

It is beautiful.

Here I must take issue with Oliver's poem. The world is much more beautiful because she was in it.