Old School

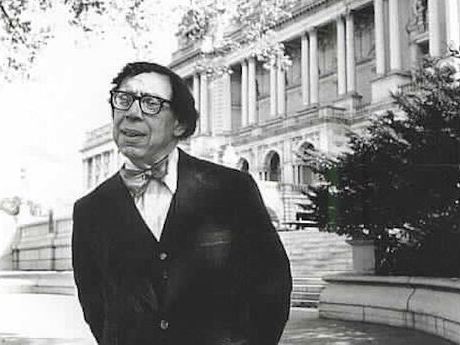

On Robert Hayden

Night, Death, Mississippi

I

A quavering cry. Screech-owl?

Or one of them?

The old man in his reek

and gauntness laughs—

One of them, I bet—

and turns out the kitchen lamp,

limping to the porch to listen

in the windowless night.

Be there with Boy and the rest

if I was well again.

Time was. Time was.

White robes like moonlight

In the sweetgum dark.

Unbucked that one then

and him squealing bloody Jesus

as we cut it off.

Time was. A cry?

A cry all right.

He hawks and spits,

fevered as by groinfire.

Have us a bottle,

Boy and me—

he's earned him a bottle—

when he gets home.

II

Then we beat them, he said,

beat them till our arms was tired

and the big old chains

messy and red.

O Jesus burning on the lily cross

Christ, it was better

than hunting bear

which don't know why

you want him dead.

O night, rawhead and bloodybones night

You kids fetch Paw

some water now so's he

can wash that blood

off him, she said.

O night betrayed by darkness not its own

"Night, Death, Mississippi" by Robert Hayden from The Collected Poems of Robert Hayden, edited by Frederick Glaysher. Copyright ©1962, 1966 by Robert Hayden. Reprinted with the permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation.

Although its topic is difficult, Hayden's "Night, Death, Mississippi" provides a model of spareness, restraint, and writing that trusts readers.

It's night, when creatures whose vision depends on light are the most vulnerable. It's Mississippi, where screech-owls are the ominous harbingers of death.

Pulled into the poem by its opening questions, readers overhear an old man wondering about a sound in the night. They hear his bet that the "cry"comes from an eerily unseen "them." Readers aware of Mississippi's history of racial conflict already suspect the cry's source. The old man, wanting certainty, "turns out the kitchen lamp" and steps into the night. He requires and chooses darkness. In the first section of the poem, Hayden uses an exterior narrator to sketch the old man's character, past, and empty Christianity. Hayden shows us a man left behind, who uses drink to celebrate male camaraderie, racial violence, and the agony of hatred's victims. The old man is also disappointed and grieves for his lost youth and his inability to take part in the blood-sport. Hayden describes a gaunt elderly man who is dying or at least represents the living death of racial violence. Yet Hayden suggests that more horrifying than the old man or than what is happening in Mississippi is the romanticization of racial violence: "White robes like moonlight / In the sweetgum dark." The old man's dreamlike memories of the Klan and the lynching tree seem disconcertingly out of place.

In the poem's second section, the old man's storytelling grows expansive. He is ill and lame but not passive. Instead, through storytelling, he joins in the off-stage drama of a black man's death. He testifies, makes theatre, and waits to greet the returning "Boy" with fitting gifts: a father's approval and hard liquor.

The old man has passed on racial hatred and violence to his son. Perhaps he himself was trained in much the same way. Referring to his son, the old man says "he's earned him a bottle," seeing violence as labor and its wages as alcohol, shared history, communal acceptance, "manhood," and the bonding of fathers and sons. But Hayden shows that the wages of violence are also the old man's broken body and sickness. Violence is both their cause and their result.

The horror is not only what the old man has done, or what his son is doing, but also that neither acts alone. For the old man's family, racial violence is the family's industry. They listen to the stories. They wash the blood. They call the perpetrator "Paw." The woman is not hysterical or disgusted at the sight of another man's blood on her husband's body. What could be more banal to her than killing or death or the murder of a black man? Fetch water, she says. Wash off the blood. Hayden writes wash, not clean. They can never remove murder's stain.

In the second section, as well, Hayden interjects his voice or the voice of an African-American chorus not only to sing, but also to pass judgment. The lyrical passion of the voices makes their argument against racial violence. The word lily rescues the cross from the burning white cross of the klan. Racial violence is old. From folklore, the voices raise the specter of "rawhead and bloody bones," which for African Americans includes the night rider, the grave robber, and the night's fearsome boogeyman. The voices also argue that racial violence is not a natural product. The Mississippi night is dark and black, but not evil. The night is betrayed and all things black are betrayed by a darkness in the minds of the hateful. The racial violence erupts in an old man's mind, his memory, and his body. We listen to an old man's words, a woman's words, a chorus of voices, and finally we listen to that terrible human cry, which may in some way match our own.