Q & A: American Poetry

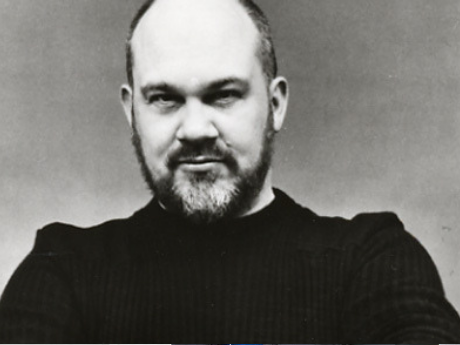

Q & A American Poetry: Tom Disch

Are there essential ways in which you consider yourself an American poet?

Yes, for it's a fact: I am American and a poet. My Americanness doesn't set an agenda for my poetry, but it determines my character in ways that are significant, surely, but not worth my own pondering. I am also bilaterally symmetrical—but I don't think much about it, though surely that fact dictates my sense of orderliness and beauty. Further, I am deeply affected by the history and multiplicity of cultures which make up America, past and present.

Do you believe there is anything specifically American about past and contemporary American poetry? Is there American poetry in the sense that there is said to be American painting or American film? Do you wish to distinguish American poetry from British or other English language poetry?

The specifically American element in American poetry (or painting or film) is not something liable to be imposed by the poet, except when he takes American history or topography as his theme. Even then a good poem about (for instance) the Mississippi River is more liable to connect with the universals of riverishness than with the flag that may fly over the river that flows by that name.

What import does regional poetry occupy in your sense of American poetry?

Any poetry of the first rank is not "regional" poetry, though some first-rank poets are more concerned with evoking a particular landscape and local culture than others.

What about the American poets who lived primarily in Europe (Eliot, Pound, Stein)? What about the European poets who have recently lived or worked in America (Heaney, Walcott, Milosz)?

Every exotic transplant, in whichever direction, is "American" in proportion as he has been shaped by a specifically American culture. Some expatriates remain very American because they don't assimilate. Eliot certainly assimilated to England much more than Stein did to France. Brodsky did his level best to achieve a dual citizenship. The barrier is probably always the language, so that other English-speaking countries are always the easiest to enter.

Are you more likely to read a contemporary non-American poet who writes in English or a contemporary non-American poet translated into English?

Few who are not native to English ever achieve complete fluency as English-language poets, so translation is always the likeliest bridge.

Do other aspects of your life (for instance, gender, sexual preference, ethnicity) figure more prominently than nationality in your self-identity as a poet?

My self-identity (what an awful coinage! are there other, non-self identities) as a poet has almost nothing to do with my nationality, gender, or food preferences. Did I like french fries more, would I be less of a poet, less of an American poet? Every poet necessarily brings his own perspective to bear on the poems he writes, and readers will favor those poets speak to their own condition, as the Quakers say. Perhaps all this fuss over "American" poetry simply derives from the size of the umbrella, for the more "American" the poet the larger the audience.

Do you believe you could readily distinguish a poem by an American poet from a poem by other poets writing in English?

Usually one can distinguish American poets from other poets by those cultural markers by which one can distinguish Americans from other peoples. But it's surely possible for any writer to write English "as if" one were English. When I lived a long while in London many of my poems took on a London tone, and to this day some readers and critics assume I am English on the basis of a few poems and mistaken assumptions as to what constitutes Americanness in poetry. Usually, lack of formal constraints and minimalist syntax.

What do you see as the consequences of "political correctness" for American poetry?

Political correctness is about as important as theological correctness was in the 18th and 19th centuries. That is to say, a very important consideration for many writers and readers and none at all for posterity, which will have its own altered sense of political correctness and find our controversies boring or beside the point. Some of the PC crowd may happen to be capable poets as well and produce viable poetry. Good poetry always transcends ideology. On the other hand, ideology can, and often does, squash poetry flat. But that is the lookout of the squashee.

What are your predictions for American poetry in the next century?

I think the effort to ballyhoo poetry into a "popular" art will continue its long, deathless fizzle. Bad poetry will flourish, unread, on the Internet, and good poetry will be circulated among good poets and some few discerning readers. The poetry of the workshops will continue as long as the economy booms. Universities can absorb vast amounts of discretionary income, and teachers for such workshops should always be as easy (and cheap) to recruit as grape pickers. Anyone can do the job. Undoubtedly I'm missing some major catalyst for change stirring even now in the womb of time, for prophets tend to predict a victory for that element of the status quo in which they perceive some personal advantage.

Published 1999.