Q & A: American Poetry

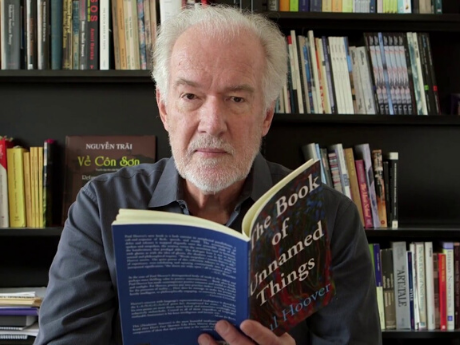

Q & A American Poetry: Paul Hoover

An ancestor on my father's side was an aide-de-camp to General Washington during the Revolutionary War. My father's uncle Will was a four-hundred-pound Virginia state senator who had to drive his Model A Ford backwards up the steeper hills of the Shenandoah Valley to prevent injury if his brakes failed. My grandfather, Paul Emmanuel Hoover, was a farmer with a B.A. who read Latin and Greek. When he died in his 40s of heartstroke while gathering hay, my father put his body on the wagon, drove the team of horses back to the house, and placed the body on the front lawn to await the doctor's arrival. This being the time of the Great Depression, the family lost the farm.

On my mother's side, an ancestor named Poage was the first settler in a picturesque area of West Virginia called "Poage's Lane." He had fled Virginia because he mistakenly thought he had killed a man in a fistfight. Known as the "Indian Killer" because he plowed his stony fields with a rifle on his back, he was killed by Cherokee warriors. My mother proudly announced that the high cheekbones in our family—my grandmother's were profound—were due to intermarriage with Cherokee people. My great-grandfather, Jacob Poage, got so drunk one night that he fell into the fireplace and burned off one of his legs. He had a peg leg after that. When I was five years old, my grandmother removed a picture from the wall to reveal a poorly patched hole made by Jacob Poage's shotgun. I was suitably impressed.

As a high-school student, my mother boarded in the Marlinton, West Virginia, home of Andrew Seidenstricker, editor of the local paper and the brother of Pearl Seidenstricker Buck, who won the Nobel Prize for literature. We visited him at the newspaper office one afternoon in the early 1950's. The clatter of the old linotype machine dropping hot type into the "chase" seemed completely to envelop us. Pearl S. Buck and my mother, who wrote a juvenile novel, The Roads to Everywhere, were among the few authors born in Pocahontas Country. This slimmest of connections to the Nobel Prize, the sound of linotype, and my mother's collection of the magazine, The Writer, which I would read sitting on the floor of the guest room where they were stored, are undoubtedly the source of my interest in writing.

Americanness, however, has little to do with the length of one's American visit, and almost nothing to do with one's identity group. Nor does his or her employment of the "American idiom" or place qualify one poet to be more American than another. This is a country of enormous social diversity. One would expect, therefore, a variety of American idioms.

A poet is the sum of his or her experiences; the most important of these experiences is reading. I'm an American poet, therefore, by way of George Herbert, Coleridge's "Frost at Midnight," Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, Emily Dickinson, Cesar Vallejo, and the French Surrealists. Vallejo's Trilce is as close to perfection of desire-in-language as one is likely to get. Stevens, Dickinson, and Vallejo especially have the ability to restore my faith in poetry. They are American, but how American are they? Is Victor Hernandez Cruz more American than Nathaniel Mackey or Sylvia Plath?

Americans are thought to smile a lot. They are "informal," "open," "innovative," and "fair-minded." They like to address others as equals. An American is Mark Twain, Sojourner Truth, and Fanny Brice pressed into one functional, playful, thoughtful, acerbic, smiling creature. Was Hart Crane more American than Orson Welles?

I am married to Maxine Chernoff, whose ancestry is Jewish, primarily Russian and Austrian. Her ancestral names include Bleistift (pencil), and mine include Schoenberg (pretty mountain). Behind her fallen Jewishness lies Orthodox Judaism; behind my fallen Protestantism lie the Amish and the Mennonites. There's something appealing about the sobriety of our ancestral garb.

In its diversity, America more or less is the world. But great poetry doesn't rise from any specific cultural tradition. It's a way of thinking and a language. A farmer from South Carolina can have as much poetry in him as a Sufi mystic or an Oxford don. But it is also true that one's social position affects the reception of the work produced.

We are inescapably part of the geography and speech we inhabit. But there are complications. When James Laughlin asked me to audition for the voice of Hart Crane for the Voices & Visions film, my speech was judged to be insufficiently Midwestern despite my having lived in the Midwest most of my life. I consider my poetry to be American because it is a "mixtery," in the words of an old blues musician, of lyricism and irony, imagery and abstraction.

America is itself a language and a metaphor. If you are American, all you have to do is open your mouth and be known for who you are. I once spoke with a black man who ran a laundromat in Glasgow, Scotland. He spoke in a thick Scottish brogue. Visitors to the United States must be just as startled by the words that come out of us: the Cambodian with a Jersey accent, the Guatemalan with the voice of Chicago's South Side.

Major American poetry began with Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman. Their poetic idioms were heavily influenced by metaphysical and romantic styles. But those styles were applied to the American situation: the expanse of a window in Amherst and the streets of Brooklyn.

The real languages of poetry are gravitas and levitas; formality and informality; concentration and dispersion; obviousness and disguise. But you speak these languages as an American.

It is the genius of our system that everyone's grandmother was once a peasant. But leaving the peasantry, as William Carlos acknowledged in his poem "To Elsie," also means leaving behind your peasant traditions or so transforming them that they resemble everyone else's. This process began under modernism and now takes the name of postmodernism. Identity affects poetry powerfully, but no poetry is great on identity alone. The Greeks called poets "makers" for a good reason. A poem is an intellectual construct in language, the "mixtery" of one's given materials. When a Mexican-American Marine wants to read the poetry of Wallace Stevens for Robert Pinsky's Library of Congress recordings, it is not out of the narcissistic needs of identity but rather a love of language. I feel the same when I read Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart, Kobo Abe's Woman of the Dunes, or Li Po's "The River Merchant's Wife: A Letter" as translated by Ezra Pound. The power of these may be enhanced by their cultural specificity, but finally it is human desire that speaks most powerfully.

There are American expressions like "barrio" and "limo" and shared cultural understandings. For example, if you're American you probably know the meaning of the words "Jerry Springer," "Kim Basinger," and "Jackie Chan." Given the kinds of media expertise Americans have, American poetry might have been characteristically satirical and parodic. It is not. Poetry has a way of considering even more puzzling things, like a rock sinking in water or the human shape of a pair of scissors.

If you watch the Jerry Springer Show, you may come to believe that Americans have begun to lose their dignity. We may indeed be "entertaining ourselves to death," as one journalist put it. But poetry sees clearly and proceeds with a "stark dignity," as William Carlos Williams wrote of spring. As you read a Charles Simic poem, something solid as sculpture rises in the mind. The poem is about a glove, its fingers curled toward a fist, which someone has left on a mailbox. Being American, you see a blue mailbox. The rest is eternity.

Published 1999.