Q & A: American Poetry

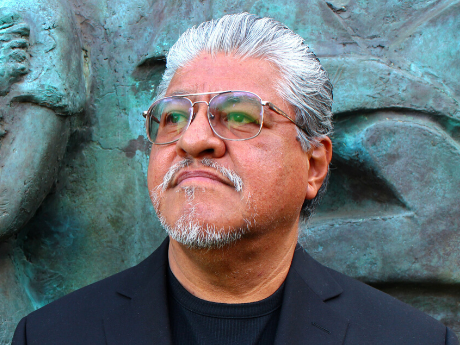

Q & A American Poetry: Luis J. Rodriguez

Thank you for inviting me to respond to your questions for the fall three-day festival of discussion and readings on "What is American about American Poetry?" My response is in the form of a free-flowing thought piece, incorporating more than a few of your questions. I hope this helps. If there is anything else I can do, please contact me. I believe in what you are doing to help make poetry an everyday, an everywhere, and an every occasion thing.

What is American about American Poetry?

I'm a poet because Walt Whitman said I should be one. "Future poets, you have to justify me," the Old Man admonished. But mostly I'm a poet because if not I will truly fail to live. I'm an American poet because this American life has impelled me toward words. America, as you know, is a stretch of land from pole to pole, what the Mexica/Aztec people called Cem-Anahuac, the complete circle, place between two waters. Besides English, we speak Spanish, Portuguese, French, as well as indigenous tongues such as Nahautl.

I dwell in the wounds of the land, within its fractured history, along the scales of our bloody song—of race, class, and gender violence. My songs are the beauty emanating from the ruins and slaughters. Poetry redeems us, even as it demands we own up to the rape of our geographical and social terrain. How can you make up for this? You can't. No one can. There are no political solutions deep enough for this! We need poetry!

Traditions: I was born on the U.S./ Mexico border; I have a foot in the empire and one in the rest of the world. We know they are two distinct realities. My traditions draw from both. In U.S. poetry circles today, there is a debate over strict and formal lines vs. open and loose ones. It appears that formal poetics are conservative and the various "experimental" forms are not. This is simplistic. But the battle lines have been drawn. Yet beneath the seemingly intense polemics over forms is the gnawing issue of where poetry connects with the people and their future. Presently, poetry is outside the center of the culture—and for good reason. It is on the edges where the heart of the culture still thrives. What is at the center is increasingly hollow. I follow the traditions that bring out our most intimate yet socially-informed intentions to the table.

American poetry:American poetry is exuberant and abundant, like the land. Neruda is the hemisphere's greatest poet in this century. In the United States, however, while the poetry is free it is also narrowly directed. Compared to verse in other countries, it is innovative, daring, and iconoclast. But it is not wise. It is not rooted. It is not as embracing. What informs U.S. poetry is the now, the unhistoricized, the drawn-out details of mundane life. The big issues are rarely tackled. Poetry is more widely accepted in our most developed countries—and many poor ones than in the United States.

Still, there are levels of poetic expression in thi country— from the native, rhymed verses of lyrics, journals, churches, and most folks (published in subsidized presses and expounded in open mike readings) to the more layered and challenged works from literary workshops, literary magazines, and academic institutes. And there are poets who are like bridges—in various ways—between the two. Besides the numerous schools of verse in this country and our regional differences, there are distinctions between African-American, Chicano, Asian, Native American, and so-called beats and slam poets. There are wholly distinguishable from British poetics. Whitman and Dickinson made sure of that more than 100 years ago.

Identity as a poet. I am indigenous. My roots are as deep as anyone else's in this soil. I am also a product of a gold-and-land lusted European invader. The Spanish destroyed as much of the native cultures as they could. Still, in Mexico, there are some 30 million traditional peoples. And the rest of the Mexicans, despite having been largely removed from tribal groups, are still predominantly of Amerindian heritage (it's a lie that we are equal parts Spanish and Indian—we are much more Indian than Spanish, and we also have significant traces of Africans and Asians than is usually acknowledged.)

I am not an immigrant—I do not recognize the border. There have been migration routes between northern and southern tribes for centuries before the European invasion. The Mexican people migrated from the northern plains to the central valley of Mexico. So when my family crossed the "border" from Mexico to the United States in the mid-1950s, we were following route patterns that were older than when the national lines were first drawn. I belong to this land; my mother's family has Tarahumara ties from the Sierras of Chihuahua. This informs my poetry as much as living in the urban malaise of present-day America. I grew up in South Central L.A. and East L.A. I presently live in "inner city" Chicago. I have worked among the abandoned, the homeless, the imprisoned, the maligned and demonized (gangs, welfare recipients, and others). Who I am, where I am, and where I've been—these concerns swirl in and out of my poetry. It tries to be a convergence between the intimate and the social—what poetry should always be.

Language. Language moves ideas. It needs to be enriched, celebrated, and kept alive. "Political correctness" makes static what are essentially concepts in motion. It's good, I believe, to have certain words mean precise things to communicate clearly. But poets are swimming in the seas of language. Science needs words to correspond to real things or processes. Poetry needs an ocean of words lapping at various shores. Language, therefore, is also a battleground. This is why "political correctness" is an issue of great contention. We know when language fails: when it no longer engages the imagination. Poetry works with truths and works with words. Sometime, in a seemingly-long gone past, they used to mean the same thing. In today's complex world, we have to fight just to get the right words to link into any compelling and significant truths.

The future of poetry. Poetry can help point the way out of our present cultural crisis. I believe that poetry as the well as all the arts are critical to this. We are living in a time characterized by "the end of work." The advanced technology, combined with a growing global economy, is changing the way we relate, trade, interact, and identify ourselves. With the birth of the transnational corporation, even the nation-state is losing its vitality. We are getting closer as people, yet we are not always sure what these transitions mean. The rise of fundamentalism, of nationalism, of segmented villages, is a direct result of the uncertainties of this period. I believe it is a time of rebalancing, of reconciling, of reaching an alignment between nature, technology, and human relationships. The chaos is prelude. We are moving from a politics of scarcity to a politics of abundance. The arts are vital now. Yet like all conscious thresholds that human beings must cross, the danger of not making it is always there. But we can't escape the direction of our path. Now, courage, clarity, and compassion have to take us through the door. Poetry, the arts, the engaged heart are necessary for all three. It is time for poetry to become a life and death issue again. I cannot go there.

Published 1999.