Q & A: American Poetry

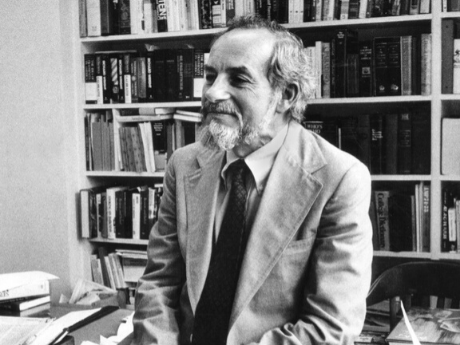

Q & A American Poetry: Harvey Shapiro

In the process of writing, I do not think of myself as an American poet. But that's because my starting point is so far back, before God separated the water and the earth, in the original chaos. So nationality hardly comes into it as I fumble for sounds that might begin to build for me a created world. On the other hand, when I'm reading I know I respond to "I had gone broke and got set to come back" (J.V. Cunningham) in a way that I don't respond to "When in the sessions of sweet silent thought" or even "They fuck you up, your dad and mum." The first is American, completely, the other two are beautiful but English—always a little exotic, and even when contemporary and slangy, as in the Larkin, museum-like, not from the conversational air I move through daily.

But this is only about langauge. Is there a substratum of concern beneath this? Probably. The major American poets, from Whitman to Oppen, are not writing in the service of the State, hardly—or to glorify America. But they are part of the national enterprise; they are part of what all of us in our thinking lives are working on: the quest for national identity. It's hard to say this without sounding chauvinistic or lapsing into clichés, but if this country is still in the process of creating something new, if it is still an escape from the history of the old world into the new (with continual reminders of how difficult that escape is, how fundamentally impossible it is), then the poets in what they are trying to create are part of that search. That is why the Alexandrian and courtly poetry of our day, as pleasurable as it is, may finally drop away or take second place to what is closer to an enterprise that Hawthorne, Melville and Whitman set in motion.

Published 1999.