Q & A: American Poetry

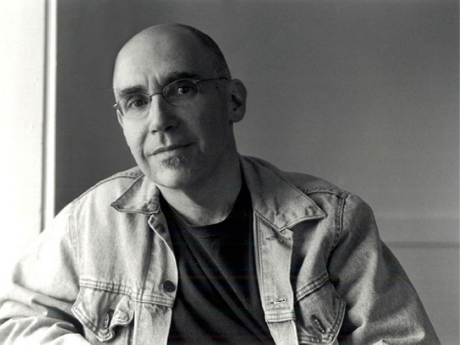

Q & A American Poetry: David Rivard

If you want to over-generalize and take the grim view, many American poets now seem caught beteen two antithetical positions—"sincerism" on the one hand, "terminal irony" and aestheticism on the other.

"Sincerism" is summed up by the kind of poetry starlet shamanism that Bill Moyers and PBS seem happy to pass off as representative of the American scene—a middlebrow expression of "feeling" and "truth" and "wisdom" that leaps to transcendent moments of self-realization not unlike those achieved in 12-step programs and at New Age spas. It's ugly. The parallel in our national politics is the distance we have traveled, in thirty years, from Robert kennedy to Bill Clinton, from heroic responsibility to the "sincerity" of I-feel-your-pain. Ugly. Much of this seems to be coming from writers above the age of 40. It's ugly most of all because it entangles in lies and false passion the project of Whitman and Williams: the possibility of a democratic poetry.

On the other hand, in writers under 40, there's the kind of poetry that prompts one critic Greg Glazner, in Countermeasures, to worry "that a full-blown anti-romanticism is choking all reach and generosity of spirit out of the contemporary scene." Having just read about 400 manuscripts by younger writers, in several award competitions, I think he's probably right to worry. A great deal of this is simply the reigning spirit of popular culture—"terminal irony." It depresses the hell out of me, though clearly my generation made the initial turn to this attitude (as if, when the passions of the 60s failed, we needed to be inoculated against ourselves.) More ugly. The problem is that, while I too long for a return to largeness of spirit, the traditional gestures employed by the Romantic sensibility have been worn out through a willed inflation, the result of over-use. That's my complaint against the sincere—sentimentality of spirit is not passion.

Interestingly, these antithetical tendencies overlap in what now passes for the avant-garde in American poetry. In both the poetry slam/performance phenomenon and the pseudo-meditative style influenced by deconstructionism and critical theory, you can often hear the earnestness of sincere speech and irony posing for itself, as well as a connection to pop culture values or knowledge. Both construe passion as a by-product of will (perhaps because they both view identity as a performance.)

So, we're doomed. Or else we're not. I think it was Robert Creeley who once said that a poetry of quality takes care of itself, always.

The central contradiction facing us is the one American and English poets have faced for the past two hundred years. It's this: how to meet head-on the self'' need and desire for transcendent motion embodied in language, while at the same time recognizing the inherent limits of language and consciousness and history. Czeslaw Milosz likes to quote Simone Weil on contradiction: "Whoever tries to escape an inevitable contradiction by patching it up is a coward." The project facing us isn't the dissolving or patching-up of our contradiction but the amplifying of it, so that we can respond authentically to the times in which we find ourselves, and to our lives.

Certain poets I look to in my generation—Dean Young, Mary Ruefle, Tom Sleigh, August Kleinzahler, Stuart Dischell, C.D. Wright, Yusef Konumyakaa, Lynn Emanuel, Forest Gander, Tony Hoagland, Lawrence Joseph, to name just a few—are doing that. These are poets of wildly different concerns and voices, but (generalizing broadly) all of them have taken up elements of the Romantic project, bringing to it an intensified sense of paradox and a vivid strangeness of approach to subject matter that owes much to one version of Modernism or another. Their precision is in service to strangeness of spirit, which is a form of passion.

The lessons Modernism holds for us have yet to be exhausted. For me, this has meant returning to Williams again and again, the Williams of the 20s and early 30s—Al Que Quiere!, Sour Grapes, Spring and All, etc. What can be found there is a clue to achieving "authenticity," as opposed to "sincerity". Williams is most often championed for his powers of seeing, and his ear for American idiom; but what I love is his faith in the inward gestures of imagination in responding to everyday life. This is what Pound means when he praises Williams' "opacity." In the waywardness of his imagination, Williams is most authentically himself (and most in touch with the possibility of freedom, a transcendent value his poems consistently enact.) Williams is interested in finding truth in what he doesn't know, in what is surprising, strange. "Sincerity," by necessity, must express what it already feels to be true, familiar—that with which it is already intimate. Williams wants us to become intimate with everything he is not. This desire is what makes his voice utterly American, individual and anonymous at once, generous, and always precise.

For Americans, strangeness and doubt and humor (not ironic giggling) have been the sources of any passionate waywardness capable of bringing closer our ideal of individual freedom. At the moment we seem lost in the pageant of consumer culture, identity politics, celebrity capitalism, multiculturalism, and self-help revivalism—all of which parade themselves as versions of realized individuality, though they are actually about conformity. In the face of these forces the wish for a national identity seems curiously innocent, even backward, primitive, or suspect, potentially dangerous, wicked. A national identity based on individual strangeness and doubt and humor is one lonely little flag these days, not many citizens are getting up in the morning to salute it. But there it is, for those who want it. I hear it in the poets I mentioned earlier, and in others both older and younger.

In his book Invisible Republic, Greil Marcus describes a metaphorical place, a town that offers that quintessential American experience, the ultimate, permanent test of the unfinished American, Puritan or pioneer, loose in a land of pitfalls and surprises." It is a place created by the spirit of those songs that are one subject of his book: the ballads of southern Appalachia, Delta blues, cowboy laments, church and dance music, all of it recorded before the mid-30's. Music made by people whose name suggest the oddness of American invention: Blind Lemon Jefferson, Prince Albert Hunt's Texas Ramblers, Bascom Lamar Lunsford, Buell Kazee, Dick Boggs, Furry Lewis, Ernest Phipps and His Holiness Singers, Eck Robertson and Family…

I've been listening to this music a lot lately, on the re-issued Anthology of American Music, originally put together in the 1950's by Harry Smith. Marcus locates the metaphorical town built by Smith somewhere in "the old weird America." In a time where many poets have adopted either the comforting earnestness of a telemarketer at an AA meeting or the know-it-all, pop irony of a Tarantino-wanna-be, it's a relief to listen to this music. Its citizens would have been familiar with the anarchic, vulnerably restless, funny spirit of someone like William Carlos Williams (and for that matter with Dickinson, Whitman, Frost, O'Hara, Creeley, Dugan, Duncan, Crane, Wright, Stern, Berryman, Ginsberg, and many others, in diverse ways). Its metaphysical subject matter is our "unfinishedness." It is all rough edges, and utter reflexes. The music has a freshness and "go to hell" heedlessness that just won't be killed. And it embodies a tradition, a tradition that exists for American poets as well.

For me, personally, that tradition has been inflected by an ironic sensibility that is not American. The irony I'm talking about is the kind used by those central European poets—Milosz, Herbert, Salamun, Zagajewski, Szymborska, Holub, etc.—who I count among my teachers. It is historical irony—a wounded sense of the mission of poetry given facts of history lived through. The hallmark of this irony is doubt registered against the backdrop of a persistent need to locate some sort of faith in either a social or spiritual realm. This doubt does not dissolve the need for faith. In these poets, irony and skepticism amplify that need through the struggle they precipitate.

Published 1999.