In Their Own Words

Wendy Chen on “They Call Me Madame Butterfly”

They Call Me Madame Butterfly

My skin is as thin

as rice paper

stretched across a frame.

My lips as red

as a temple door.

I am not like other women.

I won't walk,

won't talk

without you.

I'll wait

in a field of snow,

listening for the click

of your heels on ice,

for your black leather shoes.

When your hands

touch my cheeks—

I'll blossom

like a cherry tree.

Mouthless

flower

in the snow,

I'll raise my head.

I'll fix my eyes on you.

Won't you recognize me?

You know you do.

You were the one

wearing my voice,

making incisions

inside me.

How blank the interior!

How perfectly smooth.

Pale as the lining of a clam.

But you grow tired

of inhabiting me: retreat,

retreat from my blank

lacquered shell.

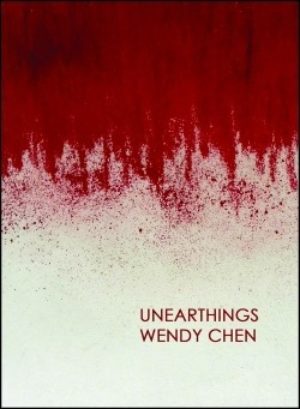

From Unearthings (Tavern Books, 2018). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "They Call Me Madame Butterfly"

In the final scene of Puccini's opera Madama Butterfly, Butterfly takes her dagger and goes behind the screen. When she emerges again, she is mortally wounded, having cut her own throat. The audience breathes a sigh of relief. At last, the expected conclusion has arrived. Butterfly is dead.

On the stage, Butterfly's pale skin is paler against the sensual red of her blood. Her silk robe is artfully arranged around her body. A stray tendril of hair curls around her cheek. She is seductive as a painted screen—ornamental, unable to speak or act. In death, she is the most submissive, and thus, the most beautiful.

"They Call Me Madame Butterfly" is part of a series of poems examining the voice and character of Madame Butterfly. The image of Madame Butterfly had continuously intrigued and frustrated me for its cultural persistence, significance, and influence on the way that Asian women and our bodies were perceived.

Growing up in America meant I had always been surrounded by images and narratives of Asian women created by and made for white men. Indeed, I was, and still am, constantly being told by men, in various iterations, that I am not American, but Chinese, Japanese, Korean, perpetual foreigner, Eastern.

This Eastern fantasy is beautiful, yes, and desired—a glimpse of her pale neck on the cover of books, a flash of her eyes behind a fan on the movie screen. But always, she is silent. One word from her might break the illusion.

Indeed, what might Madame Butterfly say if she could speak outside the boundaries drawn for her? How could I express her, my, frustrations with the ways our bodies are painted, encountered, and viewed? How could I subvert the imagery and clichés used to describe her? By writing these Madame Butterfly poems, I respond to those who would define me and turn my gaze back onto them.