In Their Own Words

Nicole Cooley on “Marriage, the Franklin Mineral Museum”

Marriage, the Franklin Mineral Museum

You and I start in the underworld, in the zinc mine,

perfect replica, with a linoleum floor and a mannequin holding

a carbide lamp. We start at the mineral dump at the bottom of the hill.

We start with the rocks. Teaspoon by teaspoon, we dig

in the quarry to find the magic rocks--rocks the color of a pink washcloth

to scrub a baby's leg, her back. Rocks the size of a fist.

The gravel pit is splintered light, all ash and bone, and our daughter wants

to talk about "Patriot Day" in school. Now, the kids are allowed

for the first time to tell their stories. Some weren't born. Most were babies.

B's mother would have died that morning but she was home with him because

he was a baby. The place where she works burned down. Rock a dilated eye.

Rocks glowing green as iceberg lettuce. Fever bright.

Rock a split heart, rock all ventricle, rock hard arterial under

the earth where the E train rushes, the day I waited

at the escalator at the top of the PATH terminal to tell you

about the baby. Teaspoon by teaspoon. Our daughter wants

me to repeat the story of how I held her on my lap,

how we watched TV while the tunnels shut down,

how we sealed the windows with towels and cloth diapers

to keep the smoke out. Now, at the shack on the hill,

we wash rocks in a bucket of mud water.

We bathe them in mineral light so they light up, too fluorescent.

Flinkite for fidelity. Otavite for hold me close. Albite for

just get up off the mattress.

Rocks spilled and spilling. Too bright—

Take me to the local room. The Fluorescent Room. The Fossil Room.

The safe room. The room without history.

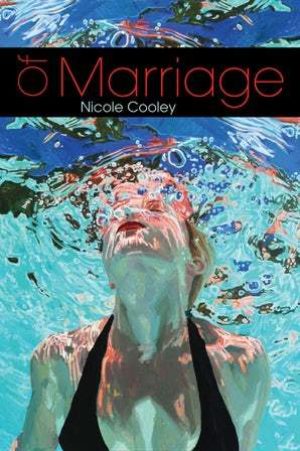

From Of Marriage (Alice James Books, 2018) All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Marriage, the Franklin Mineral Museum"

This poem was first sparked by a lunch in Atlanta with a beloved poet friend years ago, when my first book came out. After we finished our burritos, she took out a clean napkin and a pen and wrote down ten words. Then she handed me the napkin.

"Here you go," she told me, "These are the ten words you are never allowed to use in your poems again."

I was shocked and—honestly—a little bit mad. I bargained. I begged for some of my favorites back—"ribs," "dress," "girl." No, my friend insisted. "Your lexicon is too narrow. You used up those words," she said. "You need a new vocabulary."

And this moment, this list on a napkin, which I still have, forever changed the way I think about my poems.

Years later, I am still trying to do what my friend asked me to do—to shake up my usual language. One of my favorite ways to do it is to go to places with new languages. I love international travel, but that is not what I mean.

Now I go to museums to find a new language.

Not art museums, not museums that exhibit fine art at all. Instead, I have visited a crime museum, a lock museum, a bottle museum, a cotton museum, a papermaking museum, a shoe museum, a Pez museum, a purse museum, and a cocktail museum, among others. Traveling all over the country, particularly in the South where I grew up, with my husband and daughters, I've spent hours in museum after museum full of strange objects. I've taken notes. I've interviewed museum owners and visitors. And so I've found a new vocabulary. I've refreshed and rethought my language in ways I never could have imagined.

"Marriage, the Franklin Mineral Museum" appears in my new book Of Marriage, a collection that investigates marriage as a construct and institution as well as my own experience. But the poem did not start out as an exploration of marriage or relationships.

It began with a fake zinc mine and a field of rocks at a mineral museum in Northern New Jersey on a field trip with my older daughter's class. It began when I was captivated by the names of rocks, by the department store mannequins meant to be miners holding axes and lamps in the artificial mine, by the mineral light in a shed that transformed a muddy, ordinary looking rock into a sparkling pink jewel.

As I sat on the ground at the edge of the quarry, I wrote everything down. After a few pages of copying rock names, I found myself beginning to write about 9/11, and the months afterward when my husband I lived in New York City with our infant daughter, the smell of burning seeping into our apartment windows, the news playing non-stop. I remembered how I held my new baby and stared at the images, trying not to breathe too deeply, and wondering how we could raise a child in this world gripped by fear.

And then I thought of later, after we had a second child and moved to New Jersey, to a town where people had lost family members in the Towers, and the public school tried to explain/not explain what had happened once a year to the children. My older daughter had lived through this moment in history, as had her classmates, but none of them remember it unless they are told about it.

Bianchite. Microcline. Nasonite. I wrote down rock names. I remembered my daughter as a baby on my lap. I studied my daughter and her friends on the field trip.

In the end, this poem was a lesson in how to refresh my language. How to begin in one place and end up in another entirely. From words on a napkin in Georgia to a rock quarry in New Jersey to a New York apartment to a future none of us can yet imagine. Writing this poem reminds me of what I love most about writing poetry, the way it can take us on a journey we never imagined or expected.