In Their Own Words

Rowan Ricardo Phillips on “Mappa Mundi”

Mappa Mundi

These factories, their pipes' smoke, plume like skunks,

Rise as one and few and many and all

And forty fireflies bound for JFK.

Forty more circle where here be dragons.

Nature is a lapse in city life.

Whether red birds sit and sing from rooftops

Or rappers cypher deep into the night,

The gun-in-your-mouth talk of a ransomed

God, nature is a lapse in city life.

The soft green ground that ends an avenue.

The red rust-spew stifling a drain.

Pigeon-dropped icicles. Nature is a lapse in city life.

Those kids on a New Deal rooftop

Staring at the wonders of Moses,

Who with a wave split the Bronx asunder

And dropped the Cross Bronx

Down in his wake,

May they know this map of the world

As only a map of the world.

One of many that will lead them

To and from their doors.

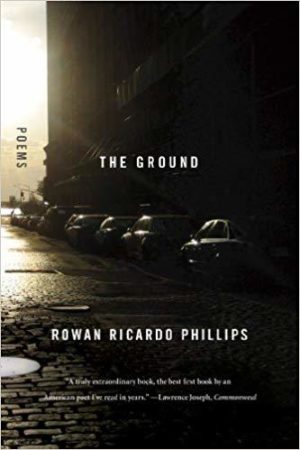

"Mapp Mundi" from The Ground (FSG 2012). Copyright © 2012 by Rowan Ricardo Phillips, Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Mappa Mundi"

"Mappa Mundi" was once another poem, completed and discarded, called "The Natural World". I am not going to include it here—unpublished work is, after all, unpublished work.

This earlier version of the poem had the same basic stanzaic shape, action, and deployment of images as "Mappa Mundi" does now but its tempo and temperament were much different: the imagination was less musical and there was far less torque between what was being seen, felt and spoken. And then there was the ending…concluding with the lines "And dropped the Cross Bronx / down in his wake", the ending entirely lacked chutzpah; it was too enchanted by its own conceit and consequently—poems, after all, are agents of consequence—made Robert Moses, and the vision of Robert Moses, controlling protagonists of the poem instead of controlled parts of the poem. Besides, that many of the neighborhoods of the Bronx are cross-stitched by highways is not the end of social life or of the imagination of the place, both of which are unassailable. And yet, ending "The Natural World" with "And dropped the Cross Bronx / down in his wake" is the type of assured poetry that abnegates the stakes involved in the very of writing poetry. Poetry is about enlivening those stakes that the mind might otherwise overlook as mere parts of the world. And that earlier version of the poem, with its conclusion as such, was too pleased with itself, with what it had accomplished; it didn't hear itself well. It was more verse than poetry.

What then was there about "The Natural World" that led me to revise it in the first place? That at its heart was sacred, trespassed territory. The pulse under this poem is many of the vistas of my youth in New York. What I came to realize as I began to travel more of the country was that these vistas were being seen by multitudes, endless millions of people, as they make their way through the country's northeast corridor. These areas were simply neighborhoods to me—

savoring an Italian ice after a baseball game as the world went by endlessly by car. Any trip north takes me, as well as all of you, up along the main arteries of the Bronx: the Cross Bronx and the Bruckner down to Florida, up to Maine and everywhere in between. But then there are the footbridges, the footbridges stapling the expressway-split Bronx together so that people can cross to do their daily business; they live in those varicolored apartment buildings in the near distance that are glimpsed from the expressways at an expressway's speed. These are lives that live perpendicularly to Robert Moses' vision of New York. The verdant Bronx slowed down life for me, so that I learned of it as a verdant place and not a misfortunate concrete corollary for going elsewhere. Its vistas taught me and summoned, in the supplest sense of the phrase, the urban sublime.

My ear brought me back to "The Natural World"…I wasn't in search of old poems to rescue, I wasn't looking to revise. Instead, when I was doing other things I found myself reciting the poem in new, feisty versions again and again. This is by and large how I compose—the ear editing and sorting out in improvised moments what stays and what goes. And so, although I only used the line "Nature is a lapse in city life" once in "The Natural World", it was that line which brought me back to the poem; it was the line that wanted to stretch its legs. It announced itself to me as the key to this particular poem's temperament, and, suddenly, out of nowhere really, I must have been walking somewhere, my ear took to playing with that line over a long period of time. You would be surprised how many poems I have revised without paper before committing them to paper. "Here be dragons" was also absent from the early version and I'm glad it found me. I grew up in homes where you couldn't turn your head without finding a map on the wall, an atlas on the coffee table. Like that the temperament was set.

And then, finally, what always comes naturally: the echo of Coleridge's "whether redbirds sit and sing" from the great "Frost at Midnight", a foundational poem in my life; and Wu Tang Clan's Raekwon starting off his verse in "Triumph" with "Aiyyo, that's amazing gun-in-your-mouth talk"—I tend to believe that speaking of influences is a lack of influence but suffice it to say Coleridge and the Wu long ago sparked something in me in a profound and sustained way. Believe it or not, this is how I speak (if you happen to know me you already know this). I tend to shrug when I see poets embrace this as a type of announced poetics, a raison d'écrire supposedly deserving of some slavish applause for simply having happened. To each their own. I heed stakes instead of stances. The pilgrimage of "The Natural World" to "Mappa Mundi" was far more of a private uncovering for me, an apocalypse of the first imagination as the second imagination is slowly revealed. This is poetry. The rest is verse.