In Their Own Words

Mike Lala on “Lydia”

Lydia

[No photography.]

Still life with compote and fruit beside

still life with compote, apples, and oranges.

[No photography.]

Still life with Purro I beside II. Young sailor

condense the meaning of his body by seeking its essential lines.

[No photography.]

Seated nude now not without her white scarf

but the scarf no longer hides her pubis.

[No photography.]

Goldfish and palette. Interior with goldfish.

Pont Saint-Michel and Police HQ

(the view outside through the window).

[No photography.]

Goldfish in bowl atop indistinct surface.

Vase of ivy on chest of drawers.

[No photography.]

Laurette as meditation, seated in pink armchair.

Seated in green robe, black background, looking down.

[No sketching.] In the light

across the street, three officers

are waiting for her figure to appear.

[No photography.]

Notre Dame, night.

Detail, wall. South façade and Seine in daylight

view through window, opposite lamplight

bridge and riverbank overlaid the floorboards, outlined, black.

[No photography. No drinking.] [I'm taking medication.]

Woman on divan. Woman in an armchair.

Paisley carpet, shuttered windows

variations on the drapes.

[Stand back, please.]

Cliff with fish. Cliff with stingrays. Cliff with single eel and white sail.

[No photography. No sketching. It holds up the crowd.]

The Large Blue Dress February 26, March 3, March 12

13, 22, 23, 24, 25, April 2 and 3, Dear

Lydia,

Every day, a photograph (I remember—).

Every day, that dress (…being stunned).

Every day, blinding in the corner and missing its other half.

[No photography.]

Lydia Delectorskaya, the author—

Lydia, the author regrets—

[No photography.]

Lydia, the author requests you simply

take your blue dress off.

[No photography.]

Point to something. It is not here.

Point because you will die

Lydia,

point as if to say the bodice

snares your roving eye.

[No photography.] Here

in the last room eight photos one painting

an empty white pedestal in the corner beside me come over here Lydia

and sit on it.

[Sir—]

Large red interior. My face in a black fern.

Your hair over me. Interior, twelve people

Egyptian cotton, eight pears, my face, just pictures

the fern outside through the window. Black now.

Light—on a white wall. [Sir…] Behind us. That year. That war.

[Sir, stand back please.] Lydia. You wouldn't believe it, Lydia. All we have

are photographs.

[Back, please.]

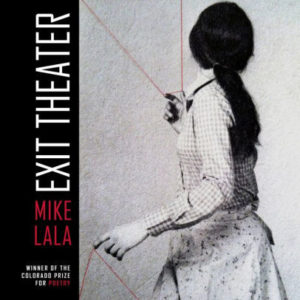

From Exit Theater (Center for Literary Publishing at Colorado State University, 2016). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Lydia"

In early 2013, I was taking a class with Rachel Zucker at NYU in which one of the assignments was to visit the exhibition Matisse: In Search of True Painting at the Metropolitan Museum—a show that included studies and drafts for what we've come to know as some of the artist's definitive paintings alongside those definitive works, often revealing changes in color, pose, small figurative elements, and even macro pictorial-compositional qualities. According to the curators, Matisse "used his completed canvases as tools, repeating compositions in order to compare effects, gauge his progress, and, as he put it, 'push further and deeper into true painting.'"

The product of these visits was to be a responsive piece of writing from each of the students that would then be read by their authors at a special event organized by Zucker and Katherine Nemeth in May of 2013. I obviously was not going to pass up on a chance to read at the Met, and as a poet who writes very slowly, often completing and then comparing three or four versions of a poem or part of a poem in order to arrive at a "final" version, the conceit of the show seemed relevant and interesting to me personally. Phrase "true painting" aside, it was a good idea for a show.

But of course, concept and execution are two different things, and my experience of Matisse: In Search of True Painting was anything but. I found it, amusingly, almost unbearably repetitive, drab, and most of all overstuffed—there were simply too many works on the walls and they were hung too close together to enable focus on any of them.

That—and, as with many well-publicized, popular shows in New York—the attendance was out of control. Not even Matisse, it seems, can compete for attention with hordes of screaming babes, mansplaining daters, flash-friendly tourists, and the cries of the gallery attendants: "No photography!"—over and over and over, gallery after gallery.

You might imagine entering that fray, proceeding along a route of slight variation with each painting, many dull, half-finished or reworked studies and sketches, finding a piece or two you liked (not always, by the way, the "final" version), only to be awoken from your gaze by that cry: "No photography!"—and move on. That was my experience, in search of any painting, as it were.

That is, until I turned the corner into a new gallery—it was a later one, in which stood a sparkling, satin-blue dress (missing the bodice; skirt only), lit so brightly it was almost blinding, an article that belonged to Lydia Delectorskaya, a Siberian refugee-turned-cleaner-turned-studio-assistant who eventually became Matisse's principal model and muse, who figures in the "Blue Dress" paintings (1937) and, from everything I can read, is likely a, if not the reason, Matisse became the giant of 20th century painting he's known as (something here of the labor of men standing on the labor of women, etc.).

In any case, my experience of the lower-case blue dress (the dress itself, not the painting) became the central aesthetic memory of that show, Matisse: In Search of True Painting, bracketed by the calls of the gallery attendants in vain to preserve the paintings' colors against the onslaught of flash photography and step-toing. And Delectoskaya's life—one of interwar, interrevolution displacement, gendered labor, and a certain historical crossroads, became the backdrop against which my poem, "Lydia," could enter.