In Their Own Words

Khaty Xiong's “Pork Rinds, Watered Rice“

Pork Rinds, Watered Rice

It seemed a powerful thing my mother being a chili picker

withstanding the burn of broken chilies hotly licking her fingers,

stomaching the only meal for the day: pork rinds and watered rice,

a warm can of Pepsi, a bite of a Thai chili plucked along the way,

the summer heat to melt the rest of her being, the day ending with

440 lbs, her pocket stuffed with $66 in cash.

In late evenings, she'd remove from underneath

the carpet flap of the bedroom floor, a thick white envelope

(not so mysterious), my little self waiting for her

to count, to look over, eyes instructing. I had never thought

her lonely for the act—perhaps when it seemed her body was

her only friend, the way she spoke to those hands unlike with me.

I'd watch her undress, think only of her torso, how tired

she looked, how much I loved her, the nightly ritual

in the bathroom—talking to her hands, the sound of

running water to mute the conversation.

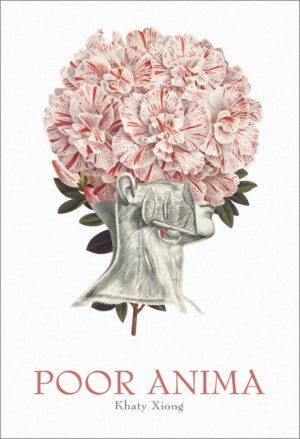

Originally appeared in The Poet's Billow as a runner-up for the 2013 Pangaea Prize, and later in debut collection Poor Anima published by Apogee Press (Berkeley, CA) in 2015. All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Pork Rinds, Watered Rice"

Born and raised in the Central Valley of California, I spent many sweltering summers picking vegetables with my parents; for years it had been one of the main sources of income for our family. We'd go to other people's farms (mostly relatives) and pick green beans or Thai chilies, hauling buckets and boxes from dawn to dusk. Despite the hard labor, it was one of my favorite summer activities. Whatever cash I had earned I'd contribute some, if not all, to my parents' earnings because I believed in the work we did, and in some ways, I felt I was helping "make ends meet." Quite simply, my parents put my siblings and me to work at an early age, and we did usually without fussing; it was one of our first lessons at learning what it meant to "earn" in this world.

My early work experience left a very big impression on me. Going to the farm was not only a place of work; it was also community, a place for socializing and connecting with other Hmong refugees who were also trying to earn their new life and presence in this strange, new world. My family, along with many Hmong refugees, came to the United States in the early 1980s as a result of the Vietnam War that left both Laos and Vietnam marred. The Hmong are a humble, nomadic group of farmers who have long resided in the jungle-covered mountains of Laos. When the Hmong arrived in the U.S., (like my family) it wasn't uncommon for them to partake in the farming business since it had not only been a form of survival for them and their ancestors centuries before, it was also closest to what their old life was like.

When I first drafted "Pork Rinds, Watered Rice," I was surprised I hadn't realized how much those experiences (and the stories I inherited) had affected my person, or what I had truly taken from them. Ultimately, the poem came from my loneliness witnessing my mother's loneliness. It wasn't easy getting her undivided attention because she was always dwelling on her struggles. It was frustrating, actually, because while I had a lot to say, I hadn't quite found my voice then either; so I did a lot of observing and reflecting in my childhood. It was apparent that I never got over this particular "act" of hers. The poem itself is vulnerability at its finest—in every way that vulnerability slays and haunts.