In Their Own Words

Kaveh Akbar on “Heritage”

Heritage

Reyhaneh Jabbari, a 26-year-old Iranian woman, was hanged on October 25th, 2014, for killing a man who was attempting to rape her.

the body is a mosque borrowed from Heaven centuries of time

stain the glazed brick our skin rubs away like a chip

in the middle of an hourglass sometimes I am so ashamed

of my sentience how little it matters angels don't care about humility

you shaved your head spent eleven days half-starved in solitary

and not a single divine trumpet wept into song now it's lonely all over

I'm becoming more a vessel of memories than a person it's a myth

that love lives in the heart it lives in the throat we push it out

when we speak when we gasp we take a little for ourselves

in books love can be war-ending a soldier drops his swordto lie forking oysters

into his enemy's mouth in life we hold love up to the light

to marvel at its impotence you said in a letter to Sholeh

you weren't even killing the roaches in your cell that you would take them up

by their antennae and flick them through the bars into a courtyard

where you could see men hammering long planks of cypress into gallows

the same men who years before threw their rings in the mud who watered them

five times daily who shot blackbirds off almond branches

and kissed the soil at the sight of sprouts then cursed each other when the stalks

which should have licked their lips withered dryly at their knees may God beat

us awake scourge our brains to life may we measure every victory

by the momentary absence of pain there is no solace in history this is a gift

we are given at birth a pocket we fold into at death goodbye now you mountain

you armada of flowers you entire miserable decade in a lump in my throat

despite all our endlessly rehearsed rituals of mercy it was you we sent on

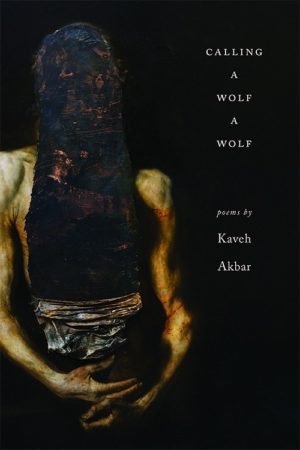

From Calling a Wolf a Wolf (Alice James, 2017). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Heritage"

When I first read about Reyhaneh Jabbari, her story completely broke me. The article that introduced me to her also included the text of her final message to her mother—to this day, that text remains among the most devastating documents I've ever encountered. There is something in the way Reyhaneh seeks to calm her mother, to relay gratitude, of all things, for her mother's love. The letter closes: "Dear soft-hearted Sholeh, in the other world it is you and me who are the accusers and others who are the accused. Let's see what God wants. I wanted to embrace you until I die. I love you."

I wanted to write about it, right then and there. But of course, there was no remove between me and the throes of my grief, my horror. Wordsworth called for poets to write from "emotion recalled in tranquility," but for me there was no recall, no tranquility. I began working with the text of Reyhaneh's final message to her mother, pulling language out, forming a kind of erasure poem of Reyhaneh's own words. My logic was: why not let her speak for herself, as she's done so eloquently? I spent the day assembling an erasure piece called "Long Polished Nails." It satisfied me formally, did all the things an erasure poem was supposed to do, but for some reason I couldn't bear to look at it. It seemed off, fundamentally wrong, and I couldn't figure out why. I put the poem away and moved on into my grieving.

About a year later I was in my regular morning writing routine, sitting in my office before sunrise surrounded by books and coffee, and as I began working on a new draft, I started noticing language that seemed eerily familiar. I was worried I was accidentally remembering lines from something I'd been reading, but I couldn't find them anywhere. Google was no help. I kept working and soon realized I was writing a new poem to Reyhaneh, through Reyhaneh. I dug up my old erasure and sure enough, the bits of language I was recognizing were recalled fragments from that early erasure poem. I kept going with the new poem and in a few hours, no time at all, I had a nearly completed draft of "Heritage," more or less in the form you see it here.

A year after consciously and unconsciously processing my grief and horror about Reyhaneh's story, my brain and soul were finally ready to write about her. I realize now my clumsy initial attempt at an erasure poem struck me as being so off not for any formal or technical reason, but because I was erasing her final words—why would I ever do that? What would compel me to take away from this already perfect, devastating final text she herself had created? What good could my meddling do? I was layering a violence over another violence—I sensed this intuitively, it's why I put that original poem away and ignored it for a year, but I didn't understand consciously until I'd written "Heritage" why my erasure had made me so queasy.

I still think about Reyhaneh all the time. No poem in my first book distresses me as much as "Heritage," and I doubt I'll ever be able to read it publicly. Still, it was important to me to include the poem, to include Reyhaneh, in Calling a Wolf a Wolf. One of the great gifts granted to the poet is the ability to amplify the voices of those who have had theirs taken away. I'm so grateful for that gift, but I'm also still trying to learn how and when to use it responsibly and with compassion.