In Their Own Words

Hadara Bar-Nadav's “Blur”

Blur

After the bombs

and the buildings blow

I call Clover, Clover

and you appear—

a dream limned in smoke.

Clover, my hermaphroditic dear,

I kiss your singed

leaflet ears and fawn

in a café in Eilat.

Clover sips from a demitasse.

Only a few sesame seeds left

and the porcelain carried away.

Morning crawls toward

afternoon and the sun

says it's time for wine

to drown this red day.

I hear there's a crater

where our bed last lay

at the Hotel de Ruin.

A portrait of dancing

lights and fire balloons,

a painterly gasoline blur.

Let's find a sailboat,

bread, za'atar, and figs

and watch the distance burn.

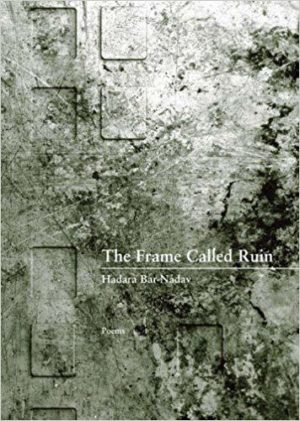

Poem reprinted from The Frame Called Ruin (New Issues, 2012). Reprinted with the permission of the author. All Rights Reserved.

On the Writing of "Blur": Suicide Bombings and Poetry

Many poems in my book The Frame Called Ruin (New Issues, 2012) investigate the intersection of beauty and destruction, of creation and devastation. "Blur" was inspired by the four people who died on January 29, 2007 when a suicide bomber blew up a bakery in Eilat, Israel. Among the dead were the bakery's two owners, an employee, and the suicide bomber.

Eilat is a breathtaking coastal city on the Red Sea and a popular tourist destination, a place where people go on honeymoons and vacations, and spend easy days snorkeling and relaxing on the beach. In "Blur" I imagined a honeymooning couple in Eilat who had bought pastries in the morning and then had coffee on the beach overlooking the purple haze of the majestic Egyptian mountain range.

Years ago, I spent a few days in Eilat after visiting my father and other family in Tel Aviv. I remember floating on the Red Sea's heavy salt water, barely moving, yet staying afloat as if the water were carrying me. The sky seemed endlessly blue and kind, and I wanted to remember that feeling of weightlessness, warmth, and peace.

Why would a suicide bomber blow up a bakery, one in a tourist area? Undoubtedly, the aim was to kill civilians and likely to negatively impact the tourist industry (apparently, the 2007 attack was the first "successful" suicide bombing in Eilat). The irony of such an act of destruction cast against the beauty of the city itself haunted me.

When I was writing "Blur," I happened to be reading Joshua Clover's The Totality for Kids (University of California Press, 2006). I borrowed the name Clover, mentioned in my poem, from Joshua Clover (a belated thanks to him) and also had learned that the clover plant was hermaphroditic. I cast the potentially self-generating clover against the self-destructive act of the bombing, and envisioned this honeymooning couple, in all of their pieces, still in love in the aftermath, or in the afterlife.

In his poem "Their Ambiguity," Clover writes: "Absurdity // is the new beauty. Ugly is the new black." This suicide bombing in Eilat was the manifestation of absurdity in waking life or, rather, the absurdity in the taking of life. If you live in Israel, as my father did prior to his death in 2007, you live with an element of absurdity, a dramatic and sometimes random reordering of experience: a child's backpack becomes a supermarket bomb, young soldiers with machine guns strapped to their backs eat ice cream cones on the street, camels are parked next to cars, fertile fields rise from the desert, modern architecture is nestled against ancient ruins, and daily life collides with violence.

When Mike's Café down the street from where my father lived in Tel Aviv was blown up, the café where he had stopped every day for coffee on his way to work, I pleaded with him to move to the United States. His response was simply to find another café to get his morning coffee. When there were repeat bombings of commuter busses, I pleaded with him again to move to the States. My father replied that he would simply start walking to work, which he claimed would be better for his health. Destruction had become part of his everyday life, but so had resilience.

My father suffered from advanced Lyme disease for more than twenty-five years and died from complications related to the disease several months after the suicide bombing in Eilat. When I began working on "Blur" I wasn't yet ready to write about my father (though my newest book, Lullaby [with Exit Sign], forthcoming from Saturnalia Books in 2013, explores his illness and death).

I nevertheless wanted to capture this idea of creativity born of destruction, of resilience in the face of devastation, that drove much of my writing in The Frame Called Ruin. If, as Akira Kurosawa famously said, "Art means never to avert your eyes," what would this imagined honeymooning couple in "Blur"—the couple who a moment before had been eating pastries and sipping coffee—have experienced after the bombing? Would beauty and love somehow still be there for them and for others? I'd like to think so, just as I'd like to think that my father experienced love and happiness in his life until the very end, amidst the beauty and devastation that was his home.