In Their Own Words

Carolina Ebeid on “Punctum / Sawing a Woman in Half”

Punctum / Sawing a Woman in Half

I ride a glorious bus. It is a metaphorical bus, or perhaps, after all, it's a machine for metaphor-making. Yes, a gospel tallyho. It stays put. It doesn't take to the highway, but it carries me places. I rev it up & it purrs out a line about Juliet. She's a bright golden ball of nuclear fire. A way of apprehending the world. My sun. My only son, now seven, teaches me a new measure: drop everything, sit on the floor & play. See it turn & turn, the red veronicas, sometimes something sharp & wounding behind his cape. When I see a blouse on a clothesline, or man's shirt next to a blouse drying outside on a stretch of cord in between the buildings, & there is wind enough so that they swing up together, & the cuff of the man's shirt grazes the cuff of the blouse, that's when I believe in the soul. My beautiful friend, Khalil, warns me it's a problem to appropriate a spirit animal, though you have to identify, he says, where your spirit belongs: water, air, or land? I think instead I have a spirit fruit. My spirit pricks like a pineapple. How it keeps growing fat in the dark. Gold & rank. A song playing in the next apartment can dismantle me. I care less & less about being beautiful. I care everyday about being less & less beautiful. When I look at an MRI of my brain, I do not believe in the soul. I love mornings because of the coffee & the possibilities. I continue to believe that poetry contains revolutionary power. Small talk is an art & best performed in the small hours with another naked in bed. I believe the most beautiful thought is that of a holy transfiguration.

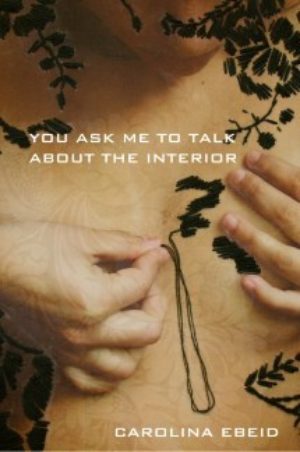

From You Ask Me To Talk About The Interior (Noemi Press, 2016). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Punctum / Sawing a Woman in Half"

I found a muteness at the center of You Ask Me to Talk About the Interior. That muteness is not only silent, but turbulent and noisy and ineloquent. The word mute can refer to a loud pack of hounds, or a hawk's defecations, or a person that doesn't speak. "Punctum / Sawing a Woman in Half" belongs to a series of interlinked "punctum" poems that are written in prose. They speak obliquely about a NYT photograph of a Palestinian man throwing a rock. Out of context, the man in the picture looks like a black-figure athlete on an ancient jug behind museum glass.

But that's a conflict where contexts are everything. I'm interested in the implied distance the rock will travel—which is a roundabout way of saying I am interested in metaphor. Through I.A. Richards we have come to understand the parts of a metaphor as having the "vehicle" and the "tenor." Observe Shakespeare's "Juliet is the sun." The woman is the tenor; "sun" is the vehicle. The measure of a fingerprint separates these nouns on the page, and approximately 93,000,000 miles separate any Juliet on Earth from the location of the sun. That's where the muteness resides, in the metaphorical distance, with all its silences and its muttering and barking. I would never place an equal sign there because that's not what is happening in between them. The poem above is a kind of bus ride through that in-between space from vehicle to tenor. It happens to be my chattiest poem.

Maybe the concepts of distance and in-betweenness have been part of my imagination ever since I was little. As a child when I listened to my father speaking Arabic—a language I never learned—I sensed a peculiar, psychic distance between my listening and his speaking, one that I could cross or not cross, wherein I'd receive his phrases, how they'd come out from that glottal place in the throat. Sounds, not words to my ear. And the sounds often meant love, or they meant I'm happy here, or more often still they meant my anger rises in me because of this stupid stupid world.

I wish I could say that I have a real-life, beautiful friend named Khalil, but I don't, unless we can count the Lebanese poet Khalil Gibran (1883––1931) who doesn't know he's my friend. I think he'd be pleased to see that I used beautiful four times in this poem. I would introduce him to my father, and we'd all ride a bus to get pistachio ice-cream.