In Their Own Words

Emma Ramadan on Ahmed Bouanani's “The Shutters”

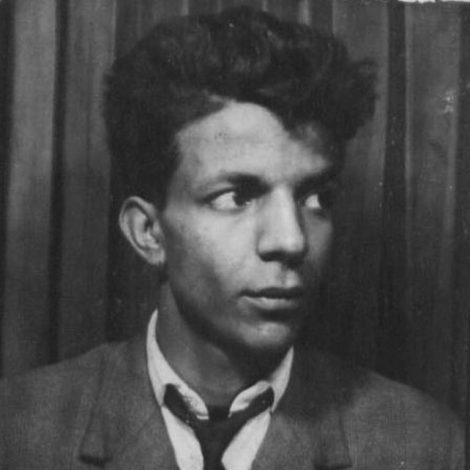

The Shutters is a book made out of memories. It insists on remembering, on telling stories of Morocco's history so that the past isn't pushed into obscurity. Its author, Ahmed Bouanani, was born in Casablanca in 1938. Through a mix of prose, prose poems, free and rhymed verse, Bouanani claws and scrapes through his country's collective memory, reconstructing vivid pictures of Morocco's past by intertwining legend and tradition with the familiar surroundings of his present. At the heart of the book stands the house with the shutters—the house where the narrator lives with his grandmother, and where his ancestors, along with a number of legendary figures, from Scheherazade to the horse-woman Al-Buraq, pass through.

While The Shutters contains references to the Second World War, the Rif War, and the Spanish and French protectorates, what is perhaps most palpable of all is the violence inflicted on Morocco by its own government during the period known as les années de plomb—the years of lead. Following Moroccan independence from the French in 1956, it became obvious to many artists and intellectuals that the battle for a liberated Morocco had only just begun. The generation that had seen its national culture wiped out by the French protectorate then saw it denied, or condemned to the realm of folklore, by the post-independence government as a way to keep the Moroccan people from uniting with anything resembling national pride. The palace took back all power; no democratic principles were instated; leftist parties were outlawed and harassed. The government assumed more control over its people through the Arabization of the education system, effectively cutting off the younger generation from any Western thought. King Hassan II persecuted democratic and progressive thinking with torture and imprisonment. In Bouanani's pages, dead soldiers, prisoners, and poets scream in their tombs with their mouths full of dirt.

As the violence and turmoil continued, living traditions were slowly erased. And if the past disappears, how can one construct a future? Bouanani believed that tradition held the keys to a country's identity. He dedicated his life to digging through his country's buried past, upholding myth over official history, and plunging into the void to bring back a vibrant heritage that was forgotten but not annihilated. He did not want to imitate what came before colonization, but instead wanted to rediscover Morocco's national heritage and critically reinvent it, something at once anchored in the ancient, in popular and oral traditions, and also infused with the new.

Many intellectuals in the 1960s and '70s decided to fight back through the written word. Early on, Ahmed Bouanani was part of the group of writers involved with the literary journal Souffles, founded by Abdellatif Laâbi and Mostafa Nissabouri. Through their journal they stressed the importance of culture in bringing about political change, the idea that through the celebration of Moroccan traditions, people could forge a stronger sense of communal identity. Bouanani published an extremely nuanced essay on oral poetry and wrote a history of Moroccan cinema. He played an active role in the Marrakech Popular Arts Festival, and made detailed drawings of Berber jewelry. In 1971, after a seven-year run, Souffles was forced to shut down; many of its principal members were arrested and tortured, while others fled the country. These individuals are the poet-prisoners of the collection Les Persiennes (The Shutters).

Create, build, rebuild on the disappearing ruins of former days. Bouanani's poetry collection Photogrammes (Photograms), also included in this volume, embodies this idea as well. He plays with classical verse forms, making unusual turns of phrase and inserting rhymes in unexpected places, or sometimes abruptly abandoning the rhyme scheme altogether. Gruesome scenes, graphic descriptions, swear words, denouncements, rage all feed into the playful lines, further heightening the contrast with the sad scenes of poverty and oppression. The poet rebels against classical forms by using them to express taboo themes. Unruly punctuation, surreal imagery, sudden tense shifts, and an always-morphing format also play into the experience of reading Bouanani's poems on his own terms.

The great Moroccan author Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine said that Bouanani's poems "invigorate a dying Maghrebi literature, which is taking refuge more and more in the fantasies of the West." His poetry bears the imprint of colonization's violence, and is written in an imposed language with a "strange alphabet." Bouanani evokes his hometown Casablanca, the odors of mats and mosques, the fear of famine, the minarets "planted in our flesh," as a way to keep his "memory intact... / the places—the names––the actions—our voices." In "The Illiterate Man," the narrator's father goes insane after reading the books left behind by his ancestors. His sanity returns only after he has used an ax to smash into pieces the chest in which the books were stored.

Ahmed Bouanani, though a prolific writer, was hesitant to publish any of his work, and was known primarily as a filmmaker during his lifetime. He directed four short films: Les quatre sources, Tarfaya ou La marche d'un poète, Six et douze (shot in Casablanca from 6:00 a.m. to noon), and Mémoire 14, which was censored from a full-length film to twenty-four minutes due to its use of archival images and footage from the Rif War. Bouanani also directed a feature-length film Le Mirage about a poor man in the 1940s who finds a stack of money in a sack of flour, which then leads him on a search for traces of collective memory in a place without any frames of reference, images of the Moroccan people's history montaged with a French-imposed modernity. Whether through films or through books, Bouanani's goal was always the same: to dive into his country's suppressed past through the lens of the present moment.

The written work Bouanani decided to publish in his lifetime comprises three volumes of poetry—The Shutters, Photograms, and the yet-to-be translated Territoire de l'instant (Land of the Moment)— as well as one novel, L'hôpital (The Hospital), a hallucinatory tale in which the hospital patients turn into prisoners. Almost as soon as the novel was published in 1990 it disappeared. Over two decades later, it was reissued in both Morocco and France to international acclaim. When Bouanani passed away in Demnate, Morocco, in 2011, he left behind a daughter, Touda Bouanani, and boxes full of unpublished manuscripts stacked in his old apartment in Rabat. In the years since her father's death, Touda has rescued these works from a devastating fire and has been making great efforts to bring his unpublished and out-of-print texts into the public light. There are notebooks, journals, essays, translations, poems, short stories, a trilogy of novels, screenplays, and many drawings still awaiting publication. Even with Touda's progress, the vast majority of his oeuvre still awaits discovery.

I received a Fulbright fellowship to Morocco in 2014 to study and translate Bouanani's work, and to help organize the incredible treasure trove of his archives. I worked alongside Touda and Omar Berrada at the Dar al-Ma'mûn artist residency, adding to the years of work they had already done to promote Bouanani's films and books, while trying to bring some of his unpublished writing into the public light. At the Dar al-Ma'mûn library, I had access to books about Moroccan history and culture, as well as books written by Bouanani's contemporaries about the political climate of their day, all of which served as necessary references in translating his poetry.

For Ahmed Bouanani, to write was to witness, to save tradition from oblivion, to wrest a people from submission. As he once wrote, "These memories retrace the seasons of a country that was quickly forgetful of its past, indifferent to its present, constantly turning its back on its future." Now, I am excited to finally share these powerful poems with the English-speaking world—poems that boldly remember in order to face the future. Thank you to Touda Bouanani, Omar Berrada, Juan Asís Palao Gómez, and the countless others working on Ahmed Bouanani's archives, for their time and help on this project during my stay in Morocco, and for their continued support.

***

What to Say

I think of the sordid streets of Casablanca

of the silent mornings

odors of Brazilian coffee

odors of rancid god

odors of bleeding dreams

I think of the too-recent day of death

and of madness

I think of those who go

far away to live out the end of a glacial tale

I think of those who stay

or who cannot go far away

or who are shut in, cut off from the sundial.

Soon I'll know what to say.

***

Before I arrived in Morocco to study and translate the work of Ahmed Bouanani, I was sent his book Les Persiennes, in English The Shutters. It completely overwhelmed me. It was a flurry of cultural, historical, and mythical references, of switching time periods and tenses, of a past I knew so little about. It was full of a pain and a love that I hadn't experienced, stacked with memories that weren't my own. Translators are expected to know every inch of a text, the meaning behind every word; that level of understanding is often necessary to translate a book. It's not enough to know the literal translation of each word in a line. To ensure that I'm not mistranslating a reference to a specific figure or moment, I need to know what is being referenced. In order to render a scene in English, I need to be able to picture that scene while reading the original language. When I first read The Shutters sitting in the sun in California, I couldn't conjure anything. I could read the book. I could perceive its beauty, its urgency, its emotion and its intellect. But I couldn't translate it. I put it aside and turned to his other works.

I spent nine months in Marrakech working alongside Ahmed Bouanani's daughter, Touda Bouanani, and the Dar al-Ma'mûn artist residency, to bring the out of print, unpublished, or forgotten texts of Ahmed Bouanani back into the public eye. I attended numerous screenings of his films, I sorted through every page of his archives, I stayed in his former apartment in Rabat, ran my fingers along the books in his library, visited the house where he lived later in life in Demnate, spent time with his granddaughter, presented on his work, read his notes to himself in the margins of his books, stared at photos of him, watched interviews with him, traced his handwriting, pieced together my own poetry from his fragments. I read everything I could about him and read the poetry and literature of his contemporaries at the Dar al-Ma'mûn library. Some days it felt like I wasn't doing enough; other days I woke up from dreams in which I had walked through the world of his work and it was clear that he had seeped into my consciousness, that I had accessed a certain level of his writing.

After nearly a year there, forming an image of Bouanani through reading, watching, observing the work he left behind, translating his fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, looking out the same window he had looked out of, eating on the same couch he had eaten on, an understanding of his work was starting to form.

When I got back to the US, I read The Shutters again and the haze had dissipated. I knew about Bouanani's early years in Casablanca, I understood many of the religious and cultural references, I could picture the streets, I understood the history of the country during the 60s and 70s, the period now referred to as the years of lead because of the repressive government's crack down on independent thinking and poetic protest. I knew what had provoked his pain and who had filled his life with love. I could glimpse the odors of rancid god, the bleeding dreams, the death, the madness, the tales. I knew where he was writing from; I had lived there. Though there were still some mysteries to unravel in the lines of The Shutters, I understood his style, his intentions, the blustering current of his poetry, his desire to communicate a specific feeling from a specific time and a specific place: his Morocco. In short, I was finally able to translate the book.