In Their Own Words

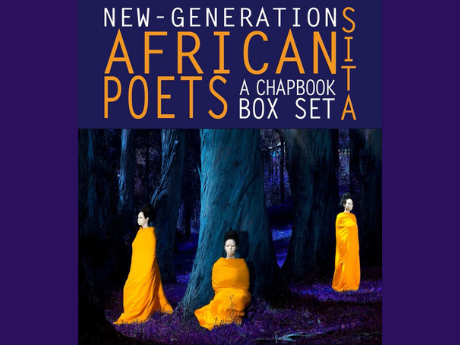

NEW-GENERATION AFRICAN POETS: A CHAPBOOK BOX SET (SITA)

NEW-GENERATION AFRICAN POETS (SITA)

An excerpt from Kwame Dawes' Introduction to the sixth set of the New-Generation African Poets Chapbook published by Akashic Books, edited by Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani.

I am interested in the ways that the traditions of the past are being challenged and ignored and the ways that they are engaged by a sense that someone may have dropped the ball in the business of passing on a legacy of the poetic arts from one generation to the next. If, indeed, the contemporary society is wrestling between traditional culture and a new modernity, then what we desire are poets with the sensitivity, intelligence, boldness, and capacity for vulnerability to write within that moment. If, indeed, something is being lost, the poetry should enact that loss. If, as is clear, the work of the emerging poets is critiquing the past and the present as well, is engaging in hip-hop but is also fascinated by the outsider discourses of marginality that characterize much of the poetry emerging in America and the UK, especially among poets of color, then it is a good thing to see that manifest in the work. I do think that the alarm over a loss of authenticity is not unfounded, but it is misplaced. The presumption is that the authentic looks a certain way and does a certain thing.

The older poets' desire for the younger poets is fundamentally that they will be proud of their culture, that they will know that their culture has a well-developed tradition of artistry and cultural power and clarity that can rival anything, and that they should not walk around the world like orphans in search of other cultures to embrace them. But what these older poets can't be consistent about is what this confidence will look like. It would be harder for some to accept that this confidence could involve acts that are tantamount to sacrilege or acts that feel compelled to critique these traditions through the prism of contemporary society. At the same time, there is a degree of justification in being concerned that some of the younger writers, in their ambition to "break into" the literary market around the world, have decided to assume the mask of those cultures in terms of their themes, their poetics, and their discourses, and that they have sought to virtually caricature their own cultures (to affirm the view that Western societies have of the African) in an effort to secure the interest and praise of Western culture.

If the Western poetics seem fascinated by the discourse of bodies, the poets will give that world bodies. If the Western perception of Africa is that the men are patriarchal and oppressive to women and that fathers are absent, they will give them men characterized in that way. And if the view is that Africa is a place of conflict characterized by the ubiquity of child soldiers and terrorists, they will generate poems that offer this idea in spades. We are, though, not alarmed at these developments and patterns, just as we are not alarmed because so many African women are writing manuscripts with the ambition to publish, and are, consequently, being published at a rate never seen before in Africa. We are not alarmed because opportunity and exposure offer correctives that are necessary in any literary movement.

Were one to identify an echo that is remarkably consistent across the work that appears in this box set, it would summarize this discussion above in some useful ways, and it would be fraught with difficulties of discourse and ideology, because these poets are consistently positioning their parents—their fathers, even—as synecdoche of some movement toward agency and, more critically, toward an emerging poetics that is refreshingly unassured.

***

Sepia

by Ama Asantewa Diaka

My parents love in sepia

a thing brewed from the slow decay of a new sprout,

seasoned and mature enough to have a feeling named after it;

teaching me that decay is not always synonymous to rot—

only a point on the growth curve.

Because this brown has seen tender and folded,

this brown has been foolish and free,

this brown has feigned sufficiency to make way for enough;

this brown with its share of pain and scars,

knows how to love the glow out of any sun.

An African Roadmap

by Charity Hutete

Everywhere,

the black tar wide and long

reaching even the land's horn

is divided by very thinly spread

white stains which run along its core

determining who goes in which

direction and who stops where.

The tar enraged,

chews itself from the edges.

It may consume itself completely

before it's free of the stain.

Naming

by Daisy Odey

I call the water over my head roof.

Now the river is home,

And drowning is an art of living.

A girl opens her mouth . . .

I walk tongue first into myself.

I call her love, and pretend she will stay.

I call my mother life, now she will live forever.

I call my father water.

I call myself wind.

Even as he leaves,

he remains the fluid part of me.

The Khartoum School: The Making of the Modern Art Movement in Sudan (1945–Present)

by Dalia Elhassan

after Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq

a complex matrix of the social

primitive imagery

averted gazes of the viewer

the abstract dimension of faith

& spirituality

achieve sacredness

indicate sainthood

achieve

untitled composition

the Khartoum School:

a chronological journey

to elucidate the necessity

for cataloguing a history

disbanded in self-exile

& imprisonment

shape the course

of Sudan transparent

their vision of the universe

is subject position

in the world

is subject to change

accordingly

Nails

by Dina El Dessouky

Noble is she

who remains anchored

to plaster and asbestos

year after year

who is overshadowed

by forced smiles and

fragile beauty

who bears the weight of

the world on her head

like a clay jug

who turned

this house

into a home

who bends

when carelessly hammered

but never crucifies

who eases into

coffins

but never dies.

A Funeral Hymn in Falsetto

February 1, 2006

by 'Gbenga Adeoba

On the night my grandfather rejected tea

and offered his last breath instead,

the earth shifted an inch.

And I listened out for a rustle of leaves

or a flash of thunder

amidst the wailers' phonation.

At the funeral,

when the chorister sang

the paradise hymn in falsetto,

I imagined a brood of angels

heralding the arrival of my grandfather

who was migrating in a boat of glass.

It is a decade now,

and sighs have replaced hymns

in the order of memories.

The elegies, too, return to me

the way an empty alley

returns our gift of words in multiples.

Getting Dressed

by Hiwot Adilow

in ruffles and taffeta, dressed in matching sweats,

in bright fuschia socks, rocking a baldie in church

pants cut into shorts, in dress shirts tied into knots,

singing the next verse chuckling under the moon.

Jupiter and Venus cloaked beneath the peachfuzz

buds on my upper lip, the few sprouts of thick hair

grown into carpets all over my killer legs, bared

like I forgot I thought shame was a virtue. I saw

rigid postures of gossip disguised as delight split

rooms in bilateral pews, the choir swayed palm up

in pomegranate gowns, babies clapped in 2/2

time entranced by praise to dance and laugh

while mothers clocked the proverbs 31 t-shirt

my mom got to announce I'd make a good bride

someday, a rib to be equally yoked, but I shirked

glory, rent my garments, ran barking toward the erotic

slobbering like Eve in the garden starved by want;

a taste of true knowledge in what I hypothesized.

The unattainable

by Musawenkosi Khanyile

I stand staring at your lips in your small room,

thirsty for the wetness of your mouth.

You've said No about four times,

even when I asked for your forehead.

We've been doing this for some time whenever I'm in Cape Town-going out for drinks, enjoying each other's company,

me wanting more, you drawing lines not to be crossed.

You ask me why I keep staring at you. I have no words.

I feel filthy. Unwanted.

In the car, I want to snatch my heart out

and only put it back when it has stopped aching.

But I will see you again.

Regardless.

Unsolvable body equation

by Nour Kamel

If a train leaves from cairo where does it go. rhodes would have made it cairo to capetown but we all know what happened to him. Nothing. the niqabi on the train wears gloves with a hole in one finger, the index, and your eyes are peeping through that slit, waiting for her to point you in the direction of history. If a train leaves from belen, new mexico it will never go anywhere again. pops tells you about every girl who called him ugly in between every euphemism he has for gay men, dated circa 1942. If a train leaves home with all your parents on it they stare as if they are all knowing. know the things you think and lie about and will never fully feel. If a train is coming and your body is on the tracks what does that body even look like anymore when everyone is looking at it. no one wants to tell you the train is coming.

Goodbye to Lampedusa

Salawu Olajide

It is what they say

because the sea does not have footprints

to see where others have ended their journeys,

and today—this incandescent afternoon—

they tell you to follow

the path of the wind,

follow it to where the water leads you

as a new merchandise arrives

with a parcel of goodbye.

Goodbye is what they tell you

as your final parting gift, so close

your heart to unholy thoughts

about the waves.