In Their Own Words

Adrian Matejka's “The Shadow Knows”

The Shadow Knows

From day one, we aspire

to be more than the average

Negro. None of that yassah

boss & watermelon rind

smile for us. We want quail

cooked in butter. We want

gold where that gap tooth

should be. Clarity for Negro

caricature. We want high-

styling clothing, gold rings

on our fingers like Greek

architecture & gold pocket

watches in our vest coats. More

women than coats. White women

all up in our architecture.

We want peculiar & instinctual

satisfactions. We want to be

prizefighting's main attraction:

the Heavyweight Champion

of the world. When we rise up

the whole Negro race rises up

with us. When we get to the top,

it's just us. No use for Negroes

then, not even ourselves.

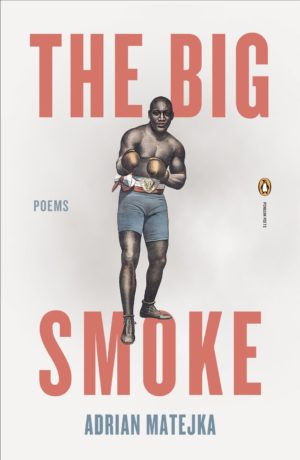

From The Big Smoke (Penguin, 2013). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "The Shadow Knows"

Jack Johnson, the first African American heavyweight champion, was one of the greatest mythmakers of the early 20th century. His skill in the ring and personality out of it were so outsized that almost anything he claimed seemed possible. When he said he hoboed from Galveston to New York City alone at age 12, everyone believed him. When he said he fought a 25-foot shark with nothing but his fists, no one questioned it.

Johnson was bigger than a billboard because he had to be. His parents were emancipated slaves and he constantly had to prove he was the physical and intellectual equal of white fighters. Johnson's mythos was two parts necessity and one part zeitgeist. He had to (appear to) be more astonishing than everyone else just to get into the conversation. His embellishments reified his humanity while simultaneously engaging in that turn of the century folkloric tradition of Americans doing big things while claiming to do have done even bigger things.

One of the problems with the colossal persona Johnson cooked up for himself is it didn't leave room for failure. The public version of Johnson could not afford to be weak and, even if he somehow came up short, he still needed to win. This predicament was on display when Johnson finally lost his title in 1915 to a less skilled fighter, Jess Willard. Johnson claimed he lost the fight on purpose as part of a deal with the U.S. government and he stuck to that explanation until his death in 1946.

The first draft of The Big Smoke was comprised exclusively of poems in Johnson's voice and it was a struggle to balance the real and imagined versions of the boxer. Reading the draft was like listening to an album on which the swag-filled lyrics change from song to song, but the melody, harmonic structure, and rhythm stays exactly the same. The narrative challenges of the project were amplified by the fact that a monologue is a monologue. Not only was there only one mode of rhetoric from the speaker, there was only one speaker.

Michael Ondaatje's Coming Through Slaughter gave me the idea of making the book a polyphonic narrative, so I developed voices for Johnson's first wife, Etta Duryea, and two of his mistresses, Hattie McClay and Belle Schreiber. I hoped that the three people closest to Johnson would help create a more nuanced view of events. But even with the addition of more objective voices, there was still an absence of emotional awareness—or maybe better, emotional honesty—from the voice of Johnson himself in the book.

That's where the "The Shadow Knows" sequence comes in. Marilyn Nelson gave me the idea—literally, she said: "You can have this idea"—of a writing poem in which a character talks to his or her shadow and it seemed an appropriate foil for an athlete who utilized shadow boxing as part of his training regimen. In the book, Shadow is the only figure who speaks directly to Johnson. He is modeled after Richard Pryor's Mudbone, and like Mudbone, Shadow calls Johnson out on his missteps in a way only a friend—real or imagined—is able. Thanks to Shadow, we get a more sophisticated understanding of Johnson's motives, ego, and most importantly, his awareness of race and culture. It is through this awareness that Shadow becomes more than just a truth teller for Johnson. Shadow speaks directly to the racial fractures of early 20th century America in a way Johnson and the other figures in the book cannot.