On Poetry

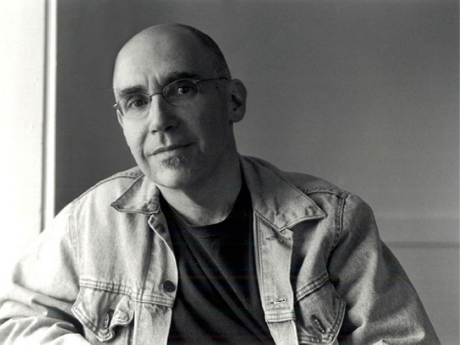

On Complexity: David Rivard

Invisible Guests

A day begins, more or less, with your five year old daughter telling you, "I scratched my momma's bed like a mole." It ends, more or less, with you stepping into your Mazda on a night of sub-freezing temperatures and noticing the smell of your freshly shined boots—the tannic sweetness of that dye-tinted alcohol and petroleum distillate waxing the very air of the car. In between are many moments likewise, each with its characteristic mood or flavor. Every one moving through you on its way, changing you.

Which is why Czeslaw Milosz says this, towards the end of "Ars Poetica?":

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at will.

There is good reason for that question mark at the end of the poem's title. It implies that the moment-by-moment flux of perception and identity will never be embodied by language, by the artifacts of consciousness. No poem will ever capture the changefulness of being, in spite of our wishing one would. Still, Milosz does begin his poem with this deceptively casual bit of rhetorical framing: "I have always aspired to a more spacious form." So the desire—enlivening and tormenting—never disappears. If it did, no one would write poems past adolescence.

Is this situation—of being alive and of writing poems—a complex or a simple matter? Both no doubt, or neither. There is something faintly laughable about the whole question of complexity in poetry, as if one could choose to be complex, or as if an objective measure existed for recording the strangeness of being awake. On both counts, the range of poetic greatness tells us otherwise. Wyatt is not Ginsberg is not Dickinson is not Wright is not Jonson is not Rich—though we say each is complex, we can hardly mean the same thing in each instance. We mean simply that they are alive, and aware of it.

Nonetheless, some people need to feel reassured about the existence of complexity. As with many other needs, this one can lead to confusion. Some of what passes as complex in poetry these days seems to confuse complexity with monumentality, as if the ambition to render some sense of being alive were a matter of largeness of scale—massed length and breadth, amplification, lots of exploded views. This version of ambition reminds me of being forced to watch a filmed recording of a crash test, one of those educational consumer reports in which a Saab or Volvo is raced into a cement wall in slow-motion. The main event is the excruciatingly drawn-out deployment of an air bag, and the depositing of a dummy's forehead thereon. The technical achievement is considerable, and one is glad even that so much of a benefit is being lavished upon humankind, but it is often deadly dull. A longer piece than this one would deal with the related social implications of a such a notion of mastery and achievement (i.e., as a marker of class identity and an illusory privilege).

So, in lieu of complexity, strangeness. In lieu of willed thought and feeling, the accident that makes an activity in the soul as it strolls or runs through this world. In lieu of the convoluted ironies of identity as a performance, the improvisations of surprised clarity. In lieu of toneless narration meant to be heard as omniscient seriousness, the dramatic intimacy of a single voice speaking. In lieu of achievement, pleasure. In lieu of wisdom, uncertainty. In lieu of earnestness, a sincerity compounded of humor and vulnerability.

As here, in this brief piece by Tomaz Salamun:

One must cook well for one's husband and pigs.

I comb my daughter's hair.

Where are you going, stars?

Some folks might think this nothing but a hiccup or pimple. But its wakefulness is considerable. Its virtues are the virtues, on the one hand, of the haiku of Basho or Issa—a quick (you could say portable) defining of a constellated moment, a flash, built playfully out of juxtaposed or collaged pieces of spare expression. Its surface seems simple, and is. Its resonance is anything but. It has that quality of haiku sometimes referred to as sabi, an undertone of aloneness that is bound up with the transience of all beings, and which fuels the poem's expansive tenderness.

On the other hand, the poem also possesses virtues one might just as easily associate with the English and Scottish ballads—a way of narrating experience that depends on elision and compression, on a wit with the subtlety and grace to leave things out. Its drama, like the drama of "Lord Randal," is charged by suggestion. Many pockets of invisible action and feeling exist inside it. It seems much larger than the sum of its pieces.

And, as my father used to say, that's about the size of it.

Originally published in Crossroads, Spring 2000.