On Poetry

On Chapbooks: Greta Goetz’s “Dendrochronology”

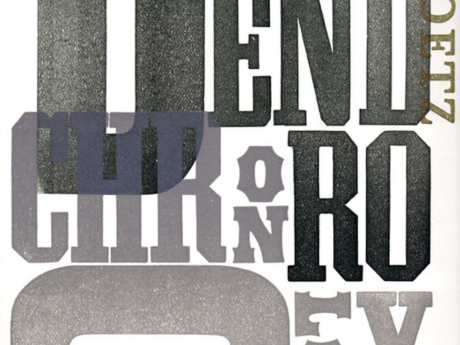

Dendrochronology by Greta Goetz

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009 / $10

* * *

I mean, wow. Greta Goetz sure can drive a poem:

What I call mother, the stormy beach of childhood

afrenzied typing on that electric machine, letters

she knew so well they got erased from the language

I had yet to learn; pacified on mantras like tinker tailor,

stop asking questions and cry baby; to grow up in that land

of indeterminacies between maids, if they could speak English at all

and adult conversations about books, I would commit to belong,

to demonstrate grace in everyone else's language, where

they all lived except me, the stranger or accent ague,

a sign more than a well-peopled phrase, the accent not concrete

enough to be riveting, just there at the edge of everyone

else's interests, homeless, alone, a mark, a reminder

of the primordial need to speak yet unable to promise

in the recognised code, there, where the horses gallop

from cave walls into eternity, or the geometric shapes

on rocks, my first words, recorded in the tomes of history

written in a language not my own, by a hand not my own,

resonating

That's the entirety of "3" from Goetz's chapbook Dendrochronology (twenty-six of the poems are numbered, and two have titles). I felt like I needed to write out the whole thing because Goetz's poems—at least her best poems in this book—are start-to-end propulsive. The poems build through fast turns ("stop asking questions and cry baby"), well-placed parallel structures ("I would commit to belong, / to demonstrate grace"; "in a language not my own, by a hand not my own"), an economy of full stops in favor of quick pauses (and even grammatically necessary pauses are barely acknowledged), and an emotional intensity with its jaw set to Here and Now.

Is that last bit misleading? Might be. These are poems of immediacy, that's what I meant, but they're also poems concerned with a human self and its history, which in this case seems to be a cuisinart of languages and places. Now, confusion and immediacy have a chicken-and-egg quality, and the particular way that Goetz's poems stretch a line from past experience to present consciousness is very much part of their force: "the reluctance to participate / in the shared experience of different views / where the self is forgotten, where words / are mere convoys in getting somewhere / but no." (from "4")

Dendrochronology is the study of tree rings, which can tell us not only the age of the tree but also what kind of conditions the tree has lived through. Goetz's poems in this chapbook are very much written to get across the conditions that prevailed as the poet rounded various corners on the path to self, but the most interesting poems here resist being "about" those conditions. Another way to put it is that Goetz's best poems don't directly report personally significant events, but instead express the sensations of living through them.

But some poems in Dendrochronology carry the logic of Goetz's project a step too far. Do you ever think that some poets' most interesting work is not the stuff where they fully indulge this or that impulse, but where they maintain a tension, some kind of resistance, to what lies at the core of their writing? I, for instance, am not a fan of Sylvia Plath's "Daddy," though I know for many people it's the quintessential Plath poem. Similarly, John Ashbery's "Europe" is not something I find myself going back to again and again, though as with Plath's "Daddy," many readers insist on the centrality of "Europe" to Ashbery's work. I think it's fair to say that each of these poems, in its own way, presents one of the poet's main concerns in stark relief, which may be why some folks like them so much. I tend to think, though, that it's usually more interesting when poets resist succumbing completely to the Big Ideas at the heart of their work, when they keep themselves from giving it all away.

There are a couple of poems in Dendrochronology that, well, give it all away, and that's actually the way it feels, as if the tension drops and the poems lose their high-wire quality. The language slackens into sentiment ("that butterfly soul") and unwieldy abstraction ("the privilege that is history and upbringing, which despite / compassion creates a blindness that cannot be broken without humility"). Given how powerful nearly every poem in Dendrochronology is, it's unfortunate that it ever lets up.