New American Poets

New American Poets: Anthony Madrid

THE MASCULINE GOD OF PASSIVE LONGING IS RIDING THE HEAD OF A FLOWER

THE masculine god of passive longing is riding the head of a flower. He fits

An arrow into the corner of his bow and draws back his right fist to his ear.

27 August 2009, last days of forty. With the Fifth Decad of THE CANTOS about to begin,

I must find a way to trick my grief.

I must find a way to trick my grief, to outstrip it—or dodge it as one dodges a cop.

For is this done by wreathing myself seven times round with elegant quickness.

The WHITE ELEPHANT is my witness. I have set up a table out front

Of the INFORMATION KIOSK that can be found at the top of his spine.

Spieglein, Spieglein an der Wand, wer ist die schönste im ganzen Land? I'll run

An extension cord up to the sun. Robe and tassel, cap and gun.

Not saying I'm a good person. I deserve what punishments I get. And yet

When it comes to men and women I have my head screwed on straight.

I know how to draw a BEADED CORD through a justbarelybigenough aperture

And then make the sound of thát into | a new kind of prosody.

Where the Monongahela River meets the mighty Allegheny

Is a jewelrybox metropolis that dare not speak its name.

And it's obvious the Founding Fathers found | the very thing they were looking for.

The busywork and distraction that come from living in a hostile environment.

And the NOSTRIL is a great conduit of the Temporality-Boggling Dharma.

But, Bhagavan, I am quits with the Temporality-Boggling Dharma.

Halloween last, I got trashed, wound up at the wrong party, fingerfucked a Sleestak.

Captain Lou Albano shook his finger in my face, but I flicked my skirt and ran around

and jammed a fork in an avocado.

Well, cock-a-doodle-doo, Sacajawea! Fuss factor fifty, and you coulda got us all killed.

You know many and many an astonishing thing. But now the CHILD wants to lecture you for a while.

All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

Introduction to the work of Anthony Madrid

Timothy Donnelly

I remember my first encounter with the poetry of Anthony Madrid. It was four years ago. He had sent a handful of poems to Boston Review, where I've worked as a poetry editor for some time, and I didn't know what to make of them. They were loud, odd, and overdressed. They were ridiculous! They snapped their fingers and walked on stilts and waxed their weird mustachios with zest. They endeavored to beguile and did. They pulled out mad allusions, aphorisms, anachronisms, factoids and all the stops. They professed, sometimes, to be sad. They wore their psychosexual complexes on their sleeve. As ghazals, they made reference to the poet himself in their last couplet, which only added to the self-conscious affect-laden razzle-dazzle of it all. Each poem was like a carnival of great big anxious ego. In the beginning, I was put off. Probably any gentle reader would be. But then, and by degrees, I was turned on. I tracked down other poems by Madrid on the internet and they were all in the same vein. This was what he did. He was focused, committed, bold. The handful of poems that had been difficult to take seriously turned out to be impossible to dismiss. By any standards, even mine, they were way too much—and yet I couldn't get enough.

This sort of thing has happened in the past. Like anyone, when I resist a new poem, food, song, show, or pretty much anything that pushes the limits of what I tend to find agreeable, prolonged or repeated exposure can teach me how to value what I at first resist. Or if it only serves to confirm my resistance, then it can possibly teach me something about what and when and why I resist. In the case of Madrid's poetry, what gave me pause was how it constantly risked violations of taste—stiltedness, floridity, bathos, camp, amorality, slapstick, decadence, etc.—and yet it managed to do so with palpable surefootedness and impeccable construction. That there's careful engineering behind the gaudiness was pretty much immediately apparent. But what I needed to see was that there was commitment to the shtick, or that the shtick wasn't shtick but a style—that this mode of Madrid's, represented by the handful of poems he had sent us, a mode measurably unlike anyone else's, wasn't just a passing fancy or a prank, but a full-blown vision with legs.

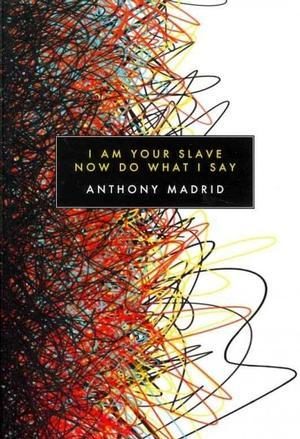

Poem after poem on the internet rewarded me with what I was looking for. If it took a little while for me to figure out where I stood with this poetry, then I'm glad for it. To have had to be won over a bit lends a sense of dimension and dynamism to my appreciation. And an excitement, too; as if when reading I Am Your Slave Now Do What I Say, his amazing, game-changing debut, I have it in mind that failure isn't only an option, it's a goddamn probability. But Madrid keeps on surpassing himself. And if he can make me laugh out loud and come dangerously close to rolling my eyes at the same time, all the better. Or it might be truer to say that he keeps on surpassing me, actually, in my capacity to predict what can be predicted of him. Just when I think I have a sense of his circumference, he up and widens it—expanding, renewing, and refreshing my sense of the possible, as only art this bold is able to, reminding me what a mind is for, what it can do.

Statement

Anthony Madrid

I believe people should write the kind of poetry they themselves want to read. That sounds simple, but it's not. Problem is everybody takes it on faith that whatever a person writes must more or less be what that person wants to look at. That's wrong. We all have to step back and consider the distinction between {wanting to write a poem} and {wanting to write a poem you yourself would want to read}.

APHORISM: Poets all write what they want, but they don't all write what they want to read.

Now, what would happen if we started teaching people to write what they actually want to read? That's easy. We'd all be ankle-deep in a bog of inert and unoriginal gunk—which is to say: things would be mainly like they are now, the key difference being that the level of pretense would be lower. And would that really be any better?

Yes. Because, the way we do things now, most poets please nobody, not even themselves—whereas, if everyone were taught to write what they themselves wanted to read, then quite a few people, hidden away and operating in harmless isolation, would be getting off on poetry, every day.

In a few exceptional cases—ones similar to my own—a poet would generate masses of immature and irresponsible lyrics, honestly seeking to please nobody but herself, and every last one of those lyrics would be truly delightful to its maker and useless to everyone else except for a few perverts, and the lyrics would find their way to those perverts, and some measure of inoffensive success might be achieved.

At any rate, this is what I intend to teach my students, next time I have any. Do the legwork, find out what you like to read. If what you really like to read is a bunch of descriptions of wieners and kwungamungas, write that. Be as deep as you are—or as shallow. Write about bees. Think hard about Dickinson, her integrity.