Interviews

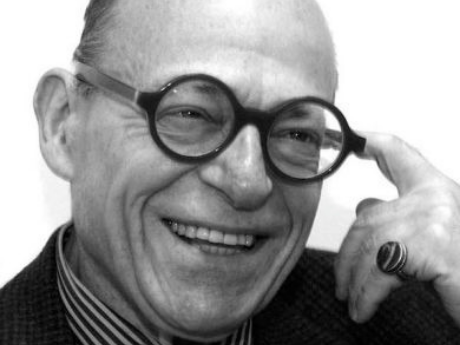

A Conversation: Richard Howard & Priscilla Becker

Priscilla Becker: I think of you as an actor, in part, or a conductor, having so many voices and personae, as you do— the voices you assume, the people you become in your poems, the translations. You seem willing, eager, to be the conduit for another's expression. So often writers, artists, seem concerned with the expression of the self. What draws you to this slant kind of expression?

Richard Howard: Well, I'm interested in self-expression too, but I don't like direct self-expression. And all the work that I do is some kind of invocation of or transaction with others, whether it's criticism, translation, or poetry. There are poems that are direct self-expression, but certainly, with some sense of preference, there is an enterprise which involves speaking through a mask, a persona. That's what the word means: sounding through—sonans per—and I like the idea of the mask or the masks, because I'm more interested in the dialogue of others than in merely the dialogue with another— the dialogue of the others who are out there, who are not me. I have written poems in which I conduct the dialogue with the other, but now my main feeling for the sort of ambitious poems that I write or want to write are other people talking and I'm not there. I'm working on a piece now about George Eliot and Cosima Wagner who did actually meet and had a week together in London while Richard (Wagner) was conducting. George Eliot was taking Mrs. Wagner around to art galleries and introducing her to intellectuals and things like that. I just had a wonderful time writing it. It's not finished but it's on its way, and I'm not there at all.

But one more thing about self-expression: I'm against self expression in poetry. I want the poet to express the poem. If the poem is satisfactory, it will be of course, inevitably, the expression of the self because this self wrote it, but it is not going to be something that is determined to be that primarily. It's going to be first of all wanting to be a poem, or the poem.

PB: You seem to like to champion underdog or obscure writers—you introduced me to Glenway Wescott, Louise Bogan, Elinor Wylie, Charlotte Mew—and also lesser known books by well-known authors, such as Rilke's The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge... Read "The Wasteland" too many times?

RH: No, I love to teach those things, but partly I like to widen or intensify the possibilities of interest in work the students have not encountered. What you call obscure is sometimes merely neglected, like Louise Bogan, for example, who was never anything but a much admired figure, or Elinor Wylie. These people fade from the contemporary consciousness which is mostly focused in our moment on the trendy and the lively. I don't think "The Wasteland" is a problem, but sometimes the idea that we can only talk about Jorie Graham or Anne Carson is irritating to me and I would like to talk about Charlotte Mew. Because there was a moment when Charlotte Mew was trendy. When you talk about being an actor or a director I wince, only because I really like to write for the page and I like the poem to be there. And when somebody says, "Oh, it's when you read it aloud that it came alive," I wince, because I really feel that it's there on the page. I hope I have a certain talent for performance, but there is a problem for me in the notion that somehow my performance has eaten up the poem to the extent that it doesn't get to people when it's read by them.

PB: What I meant was that you're not just a reader of your work.

RH: There were directors and actors twenty-five years ago who were remarkable and astonishing. We think now that Mike Nichols is the director who can bring things to life and we forget about someone like Jed Harris, who was a famous director in the twenties. There is a sense in me that I think you've located that I want to bring to the surface of consciousness, or recognition, identification, because I know about them, these other efforts. It sometimes seems to me, especially for young or new poets who are interested in obtaining a hold on their talent, that there are possibilities that have not been explored or have not been unearthed, uncovered, the stones haven't been picked up. Whatever life is crawling under there can be immensely rewarding, and I like doing that. But I wonder about the acting part of it. Yes, I mean...

PB: For instance, you do voices.

RH: Yes, that's right. I like to do it now. I really wasn't so good at it in the beginning, but now I have some sense of how to pitch the voices, and I like to do that. But I don't think that everyone should, or anything like that; it's fine not to, and as I say I have a certain reluctance about the voices taking over from the page. I'm distressed sometimes to hear people say that poetry comes alive when it's read aloud. I am still very interested in a human being in a room—alone— reading something out of a book. That is to me what I really think poetry is.

PB: One thing that has haunted me since its occurrence: I came to your apartment one early afternoon and a pile of Oscar Wilde biographies was sitting on your coffee table. You said you had to review them all. I asked what one does in such a case. "Do you skim?" I think I gauchely inquired. You replied, "Oh, no, I've already read them. This morning." I have been perplexed by this since. Care to explain?

RH: Well, by that morning I may have finished them. I remember the books involved. Some of them were very brief, very slender, others were large, but I really read them all, that I'm sure of. I remember the piece that I wrote, which I enjoyed doing. One woman wrote about the "Irish Oscar Wilde," the persistence of the Irish within him... Actually, one of the other books kept referring to him as "the great English poet, the English writer." He would have writhed at that.

PB: My question, really, is one of schedule.

RH: It's a mystery to me, but I do know that I like to do things with great intensity, project-by-project, and somehow the idea that I have these different kinds of projects—to have to do reviews, to have to make translations, to have to make poems, to judge contests, I like the variety of demands and the crowded schedule, and it seems to me that's the best way for me to get things done, to feel that I have to call upon all my resources to respond to the varying calls on my attention. It is a very blocked and complicated schedule, and indeed I suspect sometimes a chaotic one, but it's the way I have learned, in seventy years, to put things together. And I'm not sure anyone else would like it or find it appropriate. I really can get to a lot of different things in the course of a day if I attend to them. When you repeat my remark—"Yes, I read them all this morning"—it's perfectly possible that I did.

I like the pressure, I think it calls forth my best efforts. I'm very suspicious of the notion of taking off and going to write somewhere at one of those places, at Bellagio, or Ragdale. I've never been to Yaddo, and I don't think I could do it. I think the idea of going somewhere where I had nothing to do but write my own things, as opposed to having a day that was madly checkered with these other demands, would be hopeless. Or so I suspect. I've never done it.

The one time that I did take off, I had just discovered this notion of poems in dialogue and I had published a little book of them, Two-Part Inventions, and I had the insane idea that I should write a play. I went to Florence and I stayed in a villa outside it, and every day for a month I tried to write this play about Cavafy. I still have the first act, it's in verse, God help us, but it was very difficult for me. I had ten characters, I couldn't handle them, I had to put most of them to sleep, or on drugs, and I would just have two people, or just one talking. I have some dramatic impulses, but I realized that I am not a dramatist. I'm not a playwright. I know some playwrights and their capacity to keep it all alive with many people on the stage at once, ten people—Chekov, or even playwrights that I know like Edward Albee—it just astonishes me that they can do that. I'm distressed sometimes to hear people say that poetry comes alive when it's read aloud. I am still very interested in a human being in a room—alone—reading something out of a book.

PB: You conduct "workshop" in an unconventional manner, having each student individually over to your apartment, working one-on-one, and lecturing during class time. Why?

RH: Well, I feel that the attention and interest that I have for the work of a new poet is best expressed by my working with that poet. That's what I'm there for them to get, and I don't think that the policing of the workshop, which is merely keeping the various lines clear so that everybody gets a chance to talk is at all what I'm interested in. The goddamn word is a verb now, to "workshop" poems, I mean that seems just preposterous. I think it means that they are no longer being considered as poems, but as something that is a joint task, and I'm not interested in that. I like to take the group time to propose the work of our moment that is of interest to me and, I believe, to the new poets. I have always done that. There are plenty of workshops at the School of the Arts at Columbia and in other places where students can get whatever virtues and values of that discipline of the group in considering and discussing the poems as presented, I assume that's what happens. I think if I were the only person conducting some sort of critical response, it would be perhaps too bad, but since the students have four such sessions in the course of the two years, it's okay. One of them is an intimate or direct encounter with the mentor.

PB: Besides form, what can be taught to a writer?

RH: You can teach reading, the reading of poetry in general, and I think that's perhaps the most important thing. That's why I read aloud so much in class and I urge people to read aloud to themselves when they're dealing with poetry. I think learning how to read involves reading aloud at some point. I don't read aloud when I'm reading—either new poems or Milton—but I think I did, and whatever skill I have as a reader involves being able to read aloud.

I do think there are many, many things that can be taught. Besides structure, besides formal or technical devices, conventions and traditions, there is just the general sense of how to approach any text that purports to be a poem. There is some way of coming at it that only poetry requires, and that I think can be taught.

Mr. Auden used to say that poetry was "memorable speech," and, considering that that's only two words, it's not bad. The notion that something can be remembered, ought to be remembered, and will be remembered, and what are the reasons for that, what are the properties that a text or a document must have in order that it be remembered; I think that has something to do with poetry.

Obviously, a lot of prose is memorable speech, too, and indeed the difference between poetry and prose is not so clear. Mallarme used to say "prose doesn't exist: there is poetry, and there is the alphabet." And, in a sense, if you look closely enough at any prose, it breaks down into something that requires the same kind of attention that reading poetry does. Especially when the prose is great prose, or grandprose.

PB: Along those lines, what do you think the line has to offer that the sentence does not?

RH: They are not to be separated. It is what William James used to call a "double-barreled proposition," that two notions cannot be identified with each other, but they can't be separated. They are not the same thing, but they're not separable things. There are lines that are not sentences or even parts of sentences, but they are implied sentences—like "Shantih shantih shantih ," at the end of "The Wasteland." But I think lines are very crucial to most poetry, most poetry that I'm interested in, and I like to address that. About sentences: I love sentences and although sentences are the thing one likes to talk about in prose, I think there are moments in poetry when the sentence, too, is a character and one feels that it's speaking as a sentence through the text. It sets up certain expectations. That makes me happy sometimes, content, to feel that the sentence is working its way through the line.

PB: Is it your sense that people read poetry? That they like it?

RH: No. They can be induced to like it, or they can discover that they like it. I think many people like verse, and they discover that they can enjoy it, that they can be entertained or pleased by versification, and they enjoy it when it's not foolish or dreary. They can be seduced by verse, but I think most people don't like poetry, and they don't want to be told that they're going to now be exposed to it. But that situation can be modified; there are a lot of prejudicial attitudes toward different types of writing that can be altered.

I think also it is a question of how attention is directed. We can learn to like a lot of things that we don't think we like or know anything about. Learning is uncomfortable, and there But I do think that many people who say they don't like poetry like the things that poetry can do, they just don't know that it's poetry that's doing them.

PB: In your translation work, is there a credo that you can, if you had to, submit all ambiguities to?

RH: No, it varies with the text. There are no single rules that apply invariably, but there are certainly emphases. One seeks on the one hand accuracy and on the other some sort of music, and sometimes they can even come together. Sometimes one thing is sacrificed and sometimes the other. I think most people don't really like to be obliged to consider the ins and outs of translation, and it isboring. That famous phrase "the beautiful ones aren't faithful and the faithful ones aren't beautiful" is a standard canard offered to dismiss the whole process, and yet everything ultimately must be translated, and in fact, everything does invariably get translated, not necessarily right away, sometimes fifty years later or hundreds of years later, but it is a necessary part of mental life, and it must be flexible, because the texts vary so much. What one has as a translator is probably the same as what one has as a writer, and I think that's probably why most translators have had some kind of experience as writers and even as poets. Many poets do translating probably because they can apply some of the same creative principles that they do when they're writing their own things.

PB: Do you look for the next project or does it find you? Has this changed over time?

RH: Now remember I'm a veteran and I've been writing and been being asked to write for many years, so I can pretty well count on material coming my way. Although in the question of translating I like to choose and if possible to suggest things that I would like to translate and to find a publisher who's interested. Even that has happened quite attractively in the last ten or fifteen years. But at the beginning when I was making my living as a translator I had to take up anything I could get; I was happy to get whatever I could, and as a consequence translated some wretched things, but one learns a lot from translating bad books.

PB: Are yougoing to keep a poem in your pocket on Tuesday? (The first day of National Poetry Month.)

RH: As you know I have a considerable reputation as perhaps the only person in America who disapproves of National Poetry Month. And I have spoken so much and so arduously and so hostiley about it that, of course, it would be foolish of me to attend to it at all. I'm an acknowledged enemy of National Poetry Month because what happens to the other eleven? I'm not interested in that idea of ghettoizing poetry to the point where it is only to be attended to in that month, on those subway placards.

PB: What's left to do?

RH: Well, I just feel that I'm at the beginning because I know what I'm doing and I'm now eager to do the things that I know to do and there's a lot on my plate, both in translations and new poems and to some extent prose. Finally, at my age, a publisher is doing a big volume of essays that will come out next year. It's called A Paper Trail. It's a lot of the things I've written about photography and painting and other arts as well as poetry and literature, a great deal of stuff, it's a big long book, four hundred pages. I'm very happy to get that done, it's work that has accumulated over the decades and it will be followed by a sort of memoir which will be in prose, about the first twenty-five years, which is I think what is always of interest in the memoir. The rest is just literary history. That's what's to do.

There are other things that continue: the poems continue, the translations overwhelm me. The horrible thing about translations is of course that publishers have schedules and they need certain texts—they say—at certain times and you don't have them ready. It's very hard.

PB: What do you tell them?

RH: Well, I have a series of excuses, some good and some merely pathetic, and I also try more now to arrange for escapes and extensions ahead of time knowing that they'll be needed. Translation, while being something of an art is an artisanship, as well. You are to some degree in the hands of a larger undertaking that is not just you, but the author, the publisher... whereas with poetry you deliver the material when you've got it.

PB: Many poets seem to take a good long time between books.

RH: Yes, it depends if you're on good terms with your muse. There are poets who write all the time and who write well. I was thinking of Merwin, who is so steady a writer, and the work is just wonderful. I think that's what you want. There's no reason why you shouldn't be able to write all the time and well without that sense of merely waiting in between, but it's hard to get on those terms with your sources. There are many reasons to be deterred or dissuaded. For me, being around people who are writing and who want to write or are interested in writing, even if it's only in their own writing— like students—is a very useful circumstance and I find it very exciting.

And one other thing: in the class of ten or twelve, there have always been three sometimes four who are genuinely inspired and dedicated and the work is so remarkable and so interesting, it's like what happens in psychoanalysis with transference between the analyst and the patient. I think the same thing happens with the poetry teacher and the poets who are working with him. You get a certain kind of energy and vitality from the contact that the student is making with her own gift. I am not worried or discouraged by having to teach. On the contrary, it's precisely the time that isn't off, that I spend with other writers, that has been very helpful to me, very exciting, especially with the gifted students.

PB: It's my observation that you turn your attention to the positive aspects of a situation.

RH: Yes, I try to. Mr. Auden, again, who was a powerful influence on me, was very sure that criticism was appreciation. When I first met him, I had just finished five brilliant slashing reviews for Poetry magazine, and he summoned me and said, "Richard, this will never do, you're committing spiritual suicide." I took it to heart and I've really never written an attack since—maybe once or twice, something about Harold Brodkey. I won't review books that I hate.

PB: I've mentioned this before but the incident indicates how influence works its way through the mind. I'd read your poem, "Another Language," from your book, Misgivings, several years before meeting you. I liked it very much. Several years after meeting you, I wrote a poem "Vertigo." A few years after writing it, I looked at your book again and was able to see the influence, but at the time I'd had no recollection. The poems are quite different from one another, and yet... I like this example because it seems to show the difference between influence and imitation.

RH: Well, it's reading. When you really read something, you can allow it to enter you and become you, and it's thrilling. There's a realm, not the unconscious exactly, because it's verbal... Those things that you read that touch you, that shape you, you then can give back. Sometimes there are figures that are very powerful like Auden or Stevens, and you feel you have to write their poems until you can get free of them. It has happened to a number of people. It happened with Yeats and Roethke. Those late Roethke poems are all in the meters and voice of W. B. Yeats. That's a sort of terrible thing for us and it was terrible for him. In a sense, one really hopes to be taken over by the material you read; it gives you everything. It also is something that has to be transcended. But it's just wonderful when you know it's happening and you feel you're in the hands of something else. Influence, though, is deeper than imitation, and unmoderated. You can't control it in the same way.

PB: It seems you've at least met, if not known, every poet who's lived in your lifetime. Ever met a happy one?

RH: Oh there are many happy poets, and I'm one of them. I want to say that, first of all. Because I've been an editor for so long, a lot of poems come to me that I must read, and then very often because I live in New York one encounters these people, so, yes, I guess I've met an awful lot of poets, and I like to. But I don't think they strike me as less happy than anyone else that I know. On the contrary, I enjoy poets very much and I enjoy what I think of as their felicity, rather than their misery. I hope, I think that's right.

I'm interested that you ask the question, but I certainly think poets as capable of happiness and as likely to find it as anyone else that I know.

PB: I apologize for asking this but, if you had to, who is your favorite writer?

RH: It's a terrible question, of course. Two prose writers— Montaigne and Proust, two French writers; there are many English writers that I love as much, but those are the ones that seem to act upon me—and maybe five poets. And I've learned that I must have some of the ones that are considered the greatest ones. That's something that one comes to later. Milton—now—I couldn't have said that twenty-five years ago, I wouldn't have believed it.

In the book before Talking Cures, the poems about Milton's daughters, "Family Values," I was thinking about him and those girls and him being afraid that he never would finish this thing that he was doing—dictating to them, if he ever did, as he had described. I'm not so sure he regularly dictated to his daughters; I made it up. It was exciting to do it because I realized that I was really talking about this whole body of energies that meant the most to me.

But there are contemporary poets like Stevens and Auden that mean the world to me and I couldn't do without them. I don't like the idea of limiting myself at all.

Originally published in Crossroads, Fall 2003.