In Their Own Words

Incantation: a Reading of Paul Verlaine’s “Promenade sentimentale”

Promenade sentimentale / Sentimental Stroll

Le couchant dardait ses rayons suprêmes

Et le vent berçait les nénuphars blêmes;

Les grands nénuphars entre les roseaux,

Tristement luisaient sur les calmes eaux.

Moi j'errais tout seul, promenant ma plaie

Au long de l'étang, parmi la saulaie

Où la brume vague évoquait un grand

Fantôme laiteux se désespérant

Et pleurant avec la voix des sarcelles

Qui se rappelaient en battant des ailes

Parmi la saulaie où j'errais tout seul

Promenant ma plaie; et l'épais linceul

Des ténèbres vint noyer les suprêmes

Rayons du couchant dans ses ondes blêmes

Et des nénuphars, parmi les roseaux,

Des grands nénuphars sur les calmes eaux.

The setting sun cast its final rays

And the breeze rocked the pale water lilies;

Among the reeds, the huge water

Lilies shone sadly on the calm water.

Me, I wandered alone, walking my wound

Through the willow grove, the length of the pond

Where the vague mist conjured up some vast

Despairing milky ghost

With the voice of teals crying

As they called to each other, beating their wings

Through the willow grove where alone I wandered

Walking my wound; and the thick shroud

Of shadows came to drown the final rays

Of the setting sun in their pale waves

And, among the reeds, the water-

Lilies, the huge water lilies on the calm water.

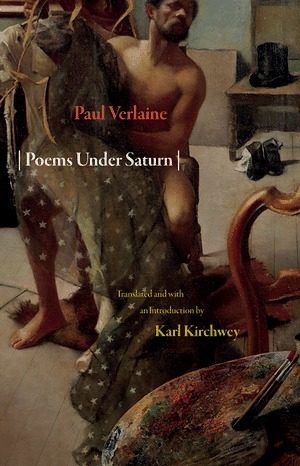

From Poems Under Saturn (Princeton University Press, 2011). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the translator.

On "Promenade sentimentale"

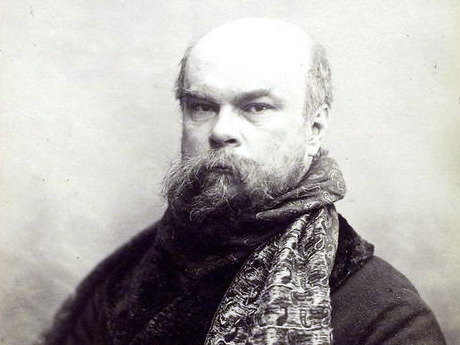

The poem called "Promenade sentimentale" is found in Paul Verlaine's first book, the Poèmes saturniens (1866), in a section called "Paysages tristes" ("Sad Landscapes"). It is a kind of show-piece of sonic effects, in a book full of virtuoso display, both intellectual and technical, on the part of its young author. The poems in this section of the book are almost all focused on a single time of day—dusk, moving into night—and are dedicated to charting a kind of psychological restlessness, mystery, and dis-ease through means both visual and aural. In his Introduction to the Pléiade edition of Verlaine's poems, Jacques Borel speaks of "the musical quality of this art [i.e. Verlaine's]…the magic of a song inseparable from tactile or visual sensations, auditory or olfactory, finally confounded, integrated into the melody through which they are made known to us" (translation mine).

I have translated the title of this poem as "Sentimental Stroll," but at the risk of sounding flippant or dismissive. Perhaps "A Feeling Walk" would be better. The title might suggest lovers walking side by side, but in fact there is only one speaker in this poem, remembering landscape with the kind of vividness that is only accessible to strong emotion, making it a kind of dreamscape too. "Moi j'errais tout seul," the speaker says— "Me, I wandered alone"—but the romantic posture of isolation is undone by the strangeness of the landscape through which the speaker travels, and by the compulsiveness with which the speaker notices things.

Verlaine's ten-syllable lines are rhymed as couplets, but what contributes more to the poem's hypnotic sonic effect is the repetition of certain words and phrases, over the course of what could be considered a sixteen-line sonnet. Thus, in the first line we find the "rayons suprêmes" ("final rays") of the setting sun, which return, enjambed and inverted, across lines 13 and 14, as the "suprêmes/ rayons." The word "nénuphars" ("water lilies") in line two is modified first by the word "blêmes" ("pale"), which makes the rhyme with "suprêmes" in the preceding line, but then recurs in line three, this time modified by "grands" ("large"), creating an incantatory rhythm through repetition. Other words and phrases are repeated, too—"saulaie" ("willow"), "roseaux" ("reeds"), "j'errais tout seul" (if the speaker says it twice, is the effect that of an echo, or of a ghostly double accompanying him?), and "promenant ma plaie" ("flashing my wound," we might say, or, "giving my wound some air, taking it for a walk"). Sometimes adjectives are recombinant with different nouns, in their repetition: it is the water-lillies that are pale, in the second line of the poem, but by the fourteenth line, it is the waves that are ("ondes blêmes"). The last line of the poem ends with a repetition of two adjective-noun phrases from the third and fourth lines: "Des grands nénuphars sur les calmes eaux," but it also follows a line in which water lilies and reeds occur unmodified by any adjectives. My own translation attempts to indicate, by means of enjambment, the unsettled valence of adjectives, in this poem: "And, among the reeds, the water/ Lilies, the huge water lilies on the calm water."

Part of the narrative beauty of this poem is the way it manages to advance in spite of its own obsessions and incantations. The voice keeps circling back to those certain details—the rays of the setting sun, the huge pale water lilies, the calm water, the willows, the fact of wandering alone, the wound that is, presumably, a spiritual or emotional wound, rather than an actual one— and they are ingeniously incorporated into the rhyme scheme. But new details also accumulate, to develop a mood that is both beautiful and stifling. This begins in the fourth line of the poem—the water lilies shine "sadly"—and continues through the "despairing" of the vague ghost-like mist for which the teals seem to ventriloquize, until at last the evening shadows, specifically likened to a burial shroud, drown the final rays of the setting sun. The waxy, deathlike flowers afloat on still waters, in the poem's last line, are a troubling final image, as if perfumed inanition had after all carried the day. We are at last securely under the spell of "the dark and powerful mixture of mystical emotion and sensual ardor that develop in Verlaine" (translation mine), as Paul Valéry once described it.