Tributes

David Gewanter on Thom Gunn

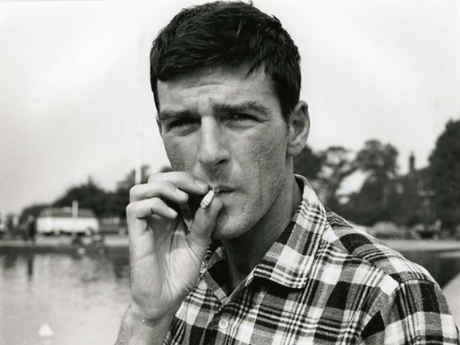

Thom Gunn was always polite, delighted at raucous jokes and banter, kept his silence at times but had a loud, boisterous laugh. He wore cowboy shirts, pointy boots, a big chain for his wallet, and a little earring. The shirts were always pressed. There was some massive tattoo on his forearm, you'd see a bit of it, and never more. Might have been a frog. Charming, withholding, fastidious, producing savage and concise poems that would shock and delight, he became a cult figure amongst the writers-manque at Berkeley, several of whom like me came to Berkeley to study with him, and then were allowed only to take one course, and then, as he said, "it's time to move on—you've gotten what you can from me." He taught only one semester a year, sharing an office and alternating days with Ishmael Reed. There were few books on the shelf; he only came to teach.

For many years he was wary of graduate students. After your one course you could show him poems, on which he would write in tiny, very antique penmanship. If you wrote to him, he'd answer on a postcard filled with tiny writing. He always spoke directly on poems, was rigorous on grammar and basic meaning on a level few essayists could sustain, while also allowing for sudden, strangely ontological- druggy explorations of identity and experience. He delighted in precise, economical expression; he liked Ben Jonson...but also Robert Duncan.

His vocal reading style was learned from F.R. Leavis, and his sense of "argument" in a poem was developed with Yvor Winters. Neither of these critics are now much known or taught, and, in fact, Gunn's training from Cambridge and Stanford, where the Renaissance lyric seemed as contemporary as Basil Bunting, and where poems stood as the first proving ground for ideas, is no longer available to most contemporary poets. A world of poetic knowledge and potential has disappeared with him. He sought human truths, and never flinched from uncomfortable ones he found, or sought. However polite, he demanded that poems not use cheap tricks, or take advantage of human stories for aesthetic effects; he disputed poems that "scored points" off of people's problems. He hated the confessional poem, said "Who wants to learn about Lowell's furniture?" But after 40 years of silence he wrote an astonishing, autobiographical poem of his mother's suicide, by inhalation of gas, when he was a teenager ("The Gas Poker").

His modesty and self-control were enormous, and unequalled, perhaps in any major poet in memory: he held his most stunning book, The Man With Night Sweats, in his drawer for ten years because he didn't want to be without poems once his book came out. When he finally published it, he had two more manuscripts finished. The book contains the greatest elegiac sequence since Thomas Hardy's Poems of 1912-13. When in conversation with Wendy Lesser, his great friend and editor, Gunn mentioned that he was surprised to hear of the reoccurring figure of "hugging" in the book. The generosity of those poems drew from a source below the creative imagination, and below the ego and its demands for recognition and reciprocity. When Gunn received a MacArthur Fellowship, he wrote the radically satiric "Troubador" lyrics about Jeffrey Dahmer.

There was some sense that his moderate workday habits were "balanced," if that's the word, but he led an entirely wild night-life, one that poked holes in—or simply stabbed—the lineaments of bourgeois life. He never owned a car, and joked that he earned "less than the salary of a bus driver," which, in fact, he might have known because, whatever was happening at Berkeley, he would leave to catch the 5:10 p.m. "F" bus to the City, where his roommates were cooking dinner, or it was his night to cook. Handsome, thin, with a twinkly gaze, he was an attractive Matterhorn to women, whom he didn't attend to much. He would tell you, "I've dyed my hair to look younger—I think it's not vanity if I tell you I've done it."

When I first hoped to write poetry I sent him some poems, terrible poems, and asked him what to do. He was the first contemporary poet I read with feeling—I was living in London—and when I later lived in San Francisco, and realized that he was teaching at Berkeley, I wrote him. His postcard, written in that ancient hand, suggested the following: "Read all the plays and poems of Shakespeare. Read the entire Norton Anthology of Poetry. And read Pound's ABC of Reading. That should get you started." A task I'm still following.

It was said that his audience was splintered. There were those who loved the formal rigor, those who appreciated the nobility and candor of gay life expressed, those who loved the radical sense of vision and experience from California, and those who wanted more from the best formalist in English, the true successor/extinguisher to T.S. Eliot, whom Thom met when he first published with Faber. All these audiences are now united in being separated from him. Because of their honesty, self-governance, and earned discoveries, because they reach so deeply in poetics, and in the self, his poems will be read and admired long after the works of more popular contemporary poets are forgotten.

Originally published in Crossroads, Fall 2004.