Tributes

Carl Phillips on Thom Gunn

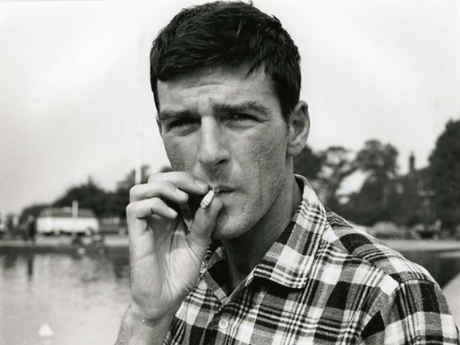

Though I'd long loved his poems, and I'd shaken his hand after one of his readings, I didn't actually meet and get to know Thom until 2000, when he spent two weeks in St. Louis as a visiting poet at Washington University. In that brief period, though, Thom's example—an odd mix of American waywardness and English decorum—both challenged and refreshed my notions not only of what it can mean to be a poet but of how to be fully alive to the world as a human being. When I try to point to specific incidents that had this effect, it doesn't work entirely. His excitement at going downtown and being shown the abandoned and gutted warehouses that make for one of the seedier parts of the Mississippi's banks? The calm with which, when I'd arrived to pick him up one morning, he asked if I'd look at the back of his head, since he'd been a bit drunk the night before, had tried to take his boots off while standing, and had fallen backwards, cutting his head on a coffee-table? His joy, first at having found an antique tip tray for his partner Mike, and the joy right after, when my partner Doug gave him a quick lesson in the art of haggling for a better price? Or his look? Or what in anyone else would be called a look, but with Thom had nothing to do with that, as far as I could tell? The leather and levis, the tattoos—these weren't about affect, it seemed to me, as he sat there addressing my prosody seminar, discussing his passage, via syllabics, into free verse, no less professorial for what he was wearing, and so much more passionate—and compassionate—than many a professor I've encountered.

He had just turned 70 that year. I kept having to try to believe that—not just because he was so fit, but because he had the spirit of any 19-year-old, if it's possible to have that spirit, minus the inexperience, minus the innocence. Thom's visit reminded me of the importance of risk, or maybe more of how wisdom and experience shouldn't be allowed to compromise taking chances, if one is to keep growing. I think that's why he continued to surprise with each new book, even as he maintained a signature style and sensibility. And I think his changes as a poet had everything to do with his constantly surprising and challenging himself as an individual—that is, he wrote as he had to and because he had to, without a careerist regard for audience; again, the life seems to have been lived in the same way, free of the by now predictable steps that most writers take from writing program to publication to university. As a poet with tenure at a university myself, I especially appreciated and learned from Thom about the seductiveness of security, the dangers in that, the need to be open to change rather than hiding in what's fixed, the need not to confuse fixity with safety or, indeed, with what might be best for the life of the self, safe or not.

There are countless types of friendship. One of the rarest, I find, is the one that springs from a relatively brief encounter and yet has permanent resonance. That's how it turns out to have been with Thom. I don't even know if he thought about me much, if at all, after that visit—we exchanged a letter or two, Doug and I sent him some cranberries from Cape Cod. But reciprocity isn't the point with this kind of friendship. On the morning that I read of Thom's death, I was shaken in a way that hasn't happened to me before, and it took me a while to figure it out. I hadn't lost anyone I'd loved before. And now I had.

Originally published in Crossroads, Fall 2004.