Tributes

A Painter Among Poets: Trevor Winkfield

Trevor Winkfield is a painter, writer, and translator. Winkfield was born in Leeds, England, in 1944, and has lived in New York since 1969. He exhibits his paintings at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York. He is the editor and translator of Raymond Roussel's How I Wrote Certain of My Books and Other Writings (Exact Change, revised edition 2005) and has worked collaboratively on books with the poets John Ashbery, Kenward Elmslie, Barbara Guest, Harry Mathews, Ron Padgett, and John Yau, among others.

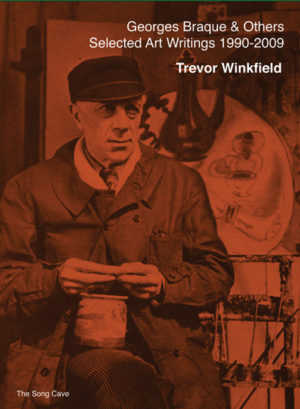

His art writings—including essays on John Graham, Jasper Johns, Gerald Murphy, Florine Stettheimer, and Vermeer—were recently published as Georges Braque and Others: The Selected Art Writings of Trevor Winkfield, 1990–2009 (The Song Cave, 2014).

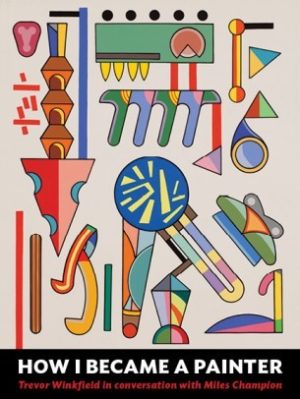

Below is an excerpt of an interview with the poet Miles Champion, from the book How I Became a Painter (Pressed Wafer, 2014). Champion's latest collection, How to Laugh, is due out from Adventures in Poetry.

* * *

Miles Champion: If Foyles [bookstore] led you to Ashbery, wasn't Better Books responsible for your first encounter with the other poets of the New York School, thanks to your finding a copy of Locus Solus—the magazine edited by Harry Mathews, not the novel by Raymond Roussel—there?

Trevor Winkfield: Yes, it was just after I'd witnessed another of their basement performances: the Fluxus artist Robin Page, who at that point had started lecturing at my old college in Leeds (he was a chum of Patrick Hughes, who was also teaching there by then, which goes to show just how rapidly things were changing in the mid-'60s), was down in the basement hacking his way through the concrete floor with a pickax, trying to dig a hole all the way to Australia! He dug quite an impressive pit, around two feet deep, before collapsing. Collapse of stout party (for such he was) followed by riotous applause. On my way out, upstairs, I noticed a small green journal by the name of Locus Solus, and knowing this to be the title of a Roussel novel, I picked it up. It turned out to be the famous collaboration issue, and it proved to be my first real immersion in New York School poetry. It was so elegantly printed—plain, even—that I felt compelled to go home and wash my hands before reading it. After that, I wrote to Harry Mathews to get the remaining issues, and since he replied from the British Embassy in Cambodia, I naturally assumed (like everyone else) that he was in the CIA (it was, after all, the height of the Vietnam War).

Miles Champion: Did you write to Ashbery as well?

Trevor Winkfield: Only one letter—I wrote asking him which Roussel book I should read first. And that was that, until I met him in the flesh when I visited New York in 1969. He turned out to be very nice, very approachable, interested in "second-tier" artists and writers, as I was. And he was quite shy . . . though not as shy as myself at the time (I was twenty-five, but only thirteen in social terms). What I liked about John, and all the other New York poets, was their diversity, their linguistic acrobatics—it was immediately obvious that these people enjoyed playing around with words and weren't just interested in bolstering a tradition, though several of them extended traditions. Just like Hopkins—my favorite English poet and the only English poet I could identify with, and who inspired me as an artist, with the exception of Betjeman. Glen Baxter summed up our mutual loathing of contemporary English poetry in one of his inimitable cartoons a few years later. If memory serves me right, it depicts a petrified fellow leaping away from a little book, shrieking, "Another slim volume of modern English poetry!" It was putrid— English poetry, that is—and both Glen and myself felt that most of it could have been written at any time during the past century. Absolutely no sense of the avant-garde. The language was dead. Whereas the New York poets seemed to talk to you and weren't merely consigning words to paper. That was just one of many differences, all in their favor.

Miles Champion: At this point, you were still involved with Ron Hunt and his group in Newcastle. When you parted ways after the second issue of Icteric in late '67, starting your own magazine must have seemed an obvious next step, especially in light of your newfound transatlantic connections.

Trevor Winkfield: Just to backtrack a little, to put one's activities into context (and to make your generation green with envy) . . . It's true that in the mid-'60s nobody had much money, but life was very cheap. I lived extremely well in London on £10 a week, which included my share of a flat (£3), a three-course meal six times a week at a Polish restaurant (seven shillings, tip included) and a trip to the cinema twice a week. Plus sundry extras, excluding holidays. So when Ron Hunt decided not to do a third issue of Icteric, my decision to start my own magazine didn't involve any financial hardship. I found a local printer in Leeds who agreed to produce two hundred copies of a forty-page offset magazine for £60, typesetting and photographs included. I'd already accumulated a certain amount of material for the proposed third issue of Icteric, so all that went in, and then I wrote to people out of the blue for unpublished material. Jasper Johns sent photographs, as did Walter de Maria. I translated some texts by Satie (whose complete writings I was foolishly contemplating collecting at the time). I also published a poem by Giorgio de Chirico—I'd just finished my Royal College thesis on his late paintings, which were incredibly scorned at that time. Harry Mathews sent me his poem "The Scruple Shop," containing the lines:

The young chief pulled her genitals apart with his fingers

Saying to me, "Here, here is something good for you to enter."

which, being a fully paid-up sophisticate by now, I'd read in all innocence (just as I'd looked at Johns's balls). But my mother, who had always been very supportive of her artistic son, demurred, and refrained from buying a copy for my Aunt Gladys.

For me, the writings of both Mathews and Ashbery exemplified a certain ideal that I cleaved to: a perfect fusion of America and Europe that combined the best of both worlds by somehow managing to mix comedy and seriousness seamlessly—no mean feat. Both were translators—I published an Arthur Cravan translation by John in one issue, some of Ungaretti's poems translated by Harry in another. Paul Auster, who was a student at Columbia University when I first met him, sent along a marvelous batch of poems by André du Bouchet ("Who is this wonderful young translator you've discovered?" I remember Harry asking), followed by some by Jacques Dupin. They've remained my favorite "contemporary" French poets ever since, despite their work being written half a century ago. As an editor I really enjoyed—and thought it not untoward—mixing the old with the new. It seemed quite natural. It's how I looked at all art—as one thing, not divided into centuries. In one issue, I put a science fiction story by Charles Cros (who had originally caught my attention as a friend of Rimbaud and the virtual inventor of both color photography and the gramophone) next to Rudy Burckhardt's Moroccan journal, both preceded by Lautréamont's letters and some of Michael Brownstein's prose poems. Alfred Jarry, Francis Jammes, Larry Fagin, Laura Riding, Ron Padgett— it was all the same to me. I wanted an interesting mix, a bit like an egghead's Reader's Digest.

Miles Champion: You named your magazine after a character in Impressions of Africa—I assume Ashbery suggested you commence your reading in Roussel with that book?

Trevor Winkfield: That's right, John recommended Impressions as a good entry point for Roussel. The magazine was named after a professor in that book, a kind of alter ego of myself. I was still undecided as to what to call the magazine even as I was walking across Leeds to deliver the manuscript to the printer. Closet Symbolist that I was, I was thinking of christening it Juillard Papered, but even I realized that was a mite pretentious, so I shortened it to Juillard virtually on the printer's doorstep.

Miles Champion: The editorial address given in the first issue (spring 1968) is Wesley Road, Leeds 12. You decided to move back after leaving the Royal College?

Trevor Winkfield: Basically it was a good mailing address—my parents' house. I was moving around, traveling. After leaving the Royal College in May '67, I traveled to Paris with Ron Hunt and his family to meet Harry Mathews, then motored south with them, my intention being to seek a job with George Brecht and Robert Filliou at their Fluxus store in Nice. Sheer lunacy! I hopped on the express train once I reached Rodez (suitably the town where Artaud had been incarcerated in an asylum) and was back in Paris overnight. I'd never been out of England before, and it felt like it.

Miles Champion: Juillard must, in anyone's estimation, figure in the top rank of mimeographed publications of the period—as one of the great "little magazines." The high quality and eclecticism of its content is all the more impressive, given the rate at which the issues were produced. Were you doing anything else at the time? Where was your £10 a week coming from?

Trevor Winkfield: I'm very flattered by your estimation. Alas, small magazines are only missed when they're no longer being published—much like the posthumous reputations of certain artists. There weren't that many issues of Juillard—nine issues spread over five years comes out to roughly two per year. Still, I did gather all the materials myself, which had the benefit of putting me in pen-pal contact with a lot of fascinating people, many of whom became close friends when I moved to the States in October '69. In England, the magazine was greeted with the usual tepid indifference (and you know how tepid the indifference can be), whereas Americans sent lots of fan mail. Ron Padgett responded almost immediately, and repeatedly. Likewise James Schuyler and Larry Fagin. Bill Zavatsky, too. I thought, "I must move to America!" This was due also to the fact that the tiny bit of money I was earning, traveling the length and breadth of England giving lectures on de Chirico, Bernard Buffet and Roussel, had begun to dry up. It was the writing on the wall—England was imploding. Nobody had any fresh ideas. Financial disaster was just around the corner, so I fled.

Miles Champion: I thought you published the first six issues before you left for the States, which would have made Juillard a quarterly rather than biannual publication, at least for the first eighteen months of its existence?

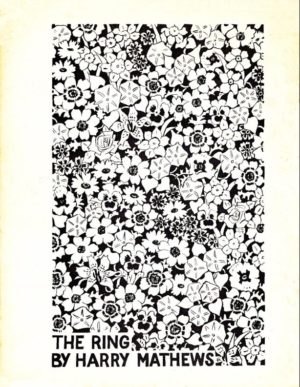

Trevor Winkfield: Of the nine issues, five were published in England—numbers 2 and 4 were mimeographed supplements to numbers 1 and 3, and number 5 was the first mimeographed issue per se (I moved over to mimeo due to lack of money). Bibliographical snots quivered irately, but everyone else loved the new format. One particular supplement, which I mimeoed at Paul Hammond's flat, broke the machine, so only thirty-nine copies were printed. Otherwise, it was always a run of two hundred copies, and even those were hard to dispose of. Around a third were given away. Poets in particular refused to pay, a character defect that hasn't ameliorated subsequently. Then in 1970 I produced the first and only Juillard Edition, Harry Mathews's The Ring, which Joe Brainard supplied a floral cover for.

I'd loved Harry's poems since being a student in London, even traipsing to various dusty (and ill-lit) research libraries to copy them out by hand. The horrors of the pre-Xerox era! Harry's poems are totally unlike anyone else's, and they'd been lying around for fifteen years without anyone having the gumption to ask Harry if he'd like them collected and published.

Miles Champion: You mentioned earlier that, "Larry Fagin, Laura Riding, Ron Padgett—it was all the same to me." I believe Ms. Riding herself wasn't quite so caught up in the giddy pluralism of the times?

Trevor Winkfield: Yes, Ms. Riding was, as expected, a prickly character, which is why I never approached her for permission to publish her poem— "The Map of Places"—in the first place. Sure enough, a month after publication, I received a handwritten envelope from her. I knew it would contain threats of a legal nature, so I gently steamed it open, read and replaced the threatening letter, resealed the envelope very carefully and scribbled "Not known at this address, try . . ." several times in various inks and hands across the front. I never heard from her again. She must have used an international web of spies to track down my poor little magazine.