Tributes

Mary Ann Caws on Pierre Reverdy

Preface from Pierre Reverdy, a selection of his poetry edited by Mary Ann Caws and translated by John Ashbery, Dan Bellm, Mary Ann Caws, Lydia Davis, Marilyn Hacker, Richard Howard, Geoffrey O'Brien, Frank O'Hara, Ron Padgett, Mark Polizzotti, Kenneth Rexroth, Richard Sieburth, Patricia Terry, and Rosanna Warren, published by NYRB/Poets.

Why Reverdy?

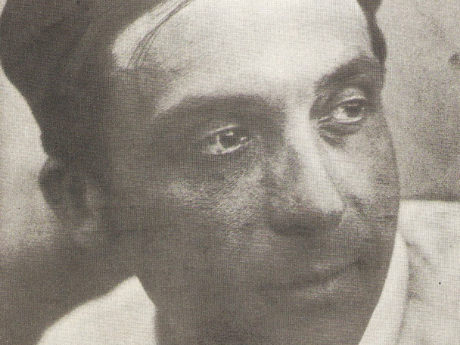

Pierre Reverdy is among the greatest of modern French poets, and certainly among the most elusive. His work is at once impersonal and intimate, crystalline and opaque, simple to the point of austerity. The landscape of his poetry is both instantly recognizable and, devoid of local specificity, imbued with an otherworldly strangeness. He is "a secret poet for secret readers," as Octavio Paz once described him, insisting on the necessity of parsing the silence, the empty spaces between what seems visible in the lines of his poems. Each feels like a fragment of a universe, and yet whole.

A single moment has a singular potential. "Just for Now," in O'Hara's translation, lays the stress on that:

Life, it's simple it's great

The clear sun rings a sweet noise

[…]

Listen, I'm not crazy

I'm laughing at the foot of the stairway

Before the great wide open door

In the espaliered sunshine

And my arms are stretched towards you

This day that I love you

It's today that I love you

The poet himself adamantly refused to have any chronology attached to his poems, or any biographical details intruding on them. He is said to have prayed, "Let me never be well-known." Nevertheless, Reverdy was a fixture of Montmartre bohemia and, for a few years during the heyday of his magazine Nord-Sud in 1917-18, at the vortex of the Parisian avant-garde. He was called the "greatest poet of his generation" by André Breton, who borrowed from Reverdy's famous essay on the image in his Surrealist Manifesto of 1924: in the image, the two elements brought together to explode in a conflagration were more exciting the more distant they were from each other. Later, when that particular enthusiasm had died down for Breton, he used to quip that he himself could indeed be boring, but that Reverdy was "even more boring than me."

Reverdy the Cubist

There was nothing boring about the texture of Reverdy's early work and its distinctive crenellated shape and experimental form. His early poems have earned him the reputation of being a cubist poet. Reverdy worked alongside painters for his entire life, and his close association with Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris is largely responsible for that label. In particular, Reverdy's close collaboration with Juan Gris lay at the origin of the poems of Au Soleil du plafond (Sun on the Ceiling), published in 1955, but first begun in 1916 or 1917. Each poem refers to one of the Spanish painter's still lifes, and the collaboration only ended with the death of Gris in 1927.

Several of Reverdy's most characteristic poems have been gathered in this volume, translated and retranslated by various hands. Together, they constitute a kind of cubist still life, perceptible from many angles at once: "From 1910 to 1914 I learned the cubist lesson," he said. Reverdy's long poem "Carrés" ["Squares"] exemplifies this on a large scale. Here is its first cube-shape, typical of his early poetry at its most sardonic:

The shameful mask hid his teeth. Another eye

saw they were false. Where is this happening?

And when? He's alone, weeping, in spite of his

pride sustaining him, and he's getting ugly. Since

it's rained, said the other one said, there's spit

on my shoes. I've grown pale and wicked. And

he kissed the mask which bit him as it sneered. [tr. by MAC]

Little by little Reverdy's poetry grew still darker. As if to consecrate his break with his worldly life in Paris—which included an intense liaison with Coco Chanel—Reverdy set fire to a bundle of his papers on a Left Bank street corner in 1926, before choosing "voluntary exile" in the monastery town of Solesmes, with his wife Henriette Charlotte Bureau, a seamstress by trade.

Reverdy the Recluse

Increasingly melancholy, increasingly bitter, Reverdy lived as a recluse in Solesmes from 1926 onward, ever more estranged from society, and eventually even from his own faith. The poem "Live Flesh," placed in this edition in three juxtaposed translations, is as raw as Reverdy can be.

When German soldiers were posted in Solesmes, Reverdy, who had made "a pact with silence" and refused to publish anything during the Occupation, wrote the excruciatingly brutal Chant des morts—violent songs of all the dead that had long lain "lodged in his throat," unable to emerge. Published in 1948, with Picasso's slashes of red surrounding Reverdy's distinctive handwriting, they read like a funereal procession. He was certainly not a cubist always, any more than Picasso.

Reverdy and Us

The impact of Reverdy on American poets has been widely noted. During the fifties and sixties, he was translated by Kenneth Rexroth in New World Writing and in a Selected Poems published by New Directions, and by John Ashbery in The Evergreen Review. Frank O'Hara memorably refers to him in his 1964 Lunch Poems:

My heart is in my

pocket, it is

"Poems by Pierre Reverdy"

—and then goes on, in the same upbeat tone, to link his name to two other avant-garde writers:

everything continues to be possible

René Char, Pierre Reverdy, Samuel Beckett it is possible isn't it

I love Reverdy for saying yes, though I don't believe it

John Ashbery (who also translated his novella Haunted House) spoke for the New York School as a whole: "Reverdy succeeds in giving back to things their true name, in abolishing the eternal dead weight of Symbolism and allegory so excessive in Eliot, Pound, Yeats, and Joyce."

Along with long-time Reverdy devotees John Ashbery, Frank O'Hara, Ron Padgett, Kenneth Rexroth, Patricia Terry, and Rosanna Warren, this volume also includes versions by some of the most respected American translators from the French—Dan Belm, Lydia Davis, Marilyn Hacker, Richard Howard, Geoffrey O'Brien, Mark Polizzotti, and Richard Sieburth —who were all invited to participate in this salute to Pierre Reverdy. From the very outset, this was a project conceived as a joint venture. Each translator was given a number of suggestions as to possible poems, chosen by the editor to represent the wide range of Reverdy's work, from early to late.

Our especial gratitude to Bill Berkson, for passing on to us the unpublished translations by Frank O'Hara, to Etienne-Alain Hubert for having encouraged this project through the time it required, and above all, to François Chapon, President of the Comité Pierre Reverdy of the Fondation Maeght.

* * *

[RETRACTION N.B.: The following erroneous statement appears in the preface to Pierre Reverdy (NYRB/Poets, 2013, ed. Mary Ann Caws, p.xiv): "His lifelong affection for Chanel (despite her collaborationist activities during WWII) would nonetheless be memorialized by the epitaph he wrote for her tomb—which ends, "Before heading toward / The dark road's end / If condemned / If pardoned / Know you are loved."

This formulation was based on the concluding sentence of the epilogue in Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel's Secret War by Hal Vaughan (Knopf, 2012, p. 222): "Before he died at seventy in 1960…Reverdy blessed Chanel in poetry. This determined and dedicated resistance fighter…willed Chanel a final epitaph." His footnote to this sentence on p. 249 reads: "Reverdy poem reprinted in Edmonde Charles-Roux, L'Irrégulière."

However, in fact, as Edmonde Charles-Roux clearly says in L'Irrégulière ou mon itinéraire Chanel (Paris: Editions Grasset, & Fasquelle, 1974, pp. 583-584), the text quoted was simply inscribed in the edition of his collection of poems, Main d'oeuvre, given to Chanel in 1949 by Reverdy, and was in no sense an epitaph. In all future printings of this book, the entire sentence will be excised. M.A.C., September 9, 2013]