Red, White, & Blue

Eileen Myles

An American Poem

I was born in Boston in

1949. I never wanted

this fact to be known, in

fact I've spent the better

half of my adult life

trying to sweep my early

years under the carpet

and have a life that

was clearly just mine

and independent of

the historic fate of

my family. Can you

imagine what it was

like to be one of them,

to be built like them,

to talk like them

to have the benefits

of being born into such

a wealthy and powerful

American family. I went

to the best schools,

had all kinds of tutors

and trainers, traveled

widely, met the famous,

the controversial, and

the not-so-admirable

and I knew from

a very early age that

if there were ever any

possibility of escaping

the collective fate of this famous

Boston family I would

take that route and

I have. I hopped

on an Amtrak to New

York in the early

'70s and I guess

you could say

my hidden years

began. I thought

Well I'll be a poet

.What could be more

foolish and obscure.

I became a lesbian.

Every woman in my

family looks like

a dyke but it's really

stepping off the flag

when you become one.

While holding this ignominious

pose I have seen and

I have learned and

I am beginning to think

there is no escaping

history. A woman I

am currently having

an affair with said

you know you look

like a Kennedy. I felt

the blood rising in my

cheeks. People have

always laughed at

my Boston accent

confusing "large" for

"lodge," "party"

for "potty." But

when this unsuspecting

woman invoked for

the first time my

family name

I knew the jig

was up. Yes, I am,

I am a Kennedy.

My attempts to remain

obscure have not served

me well. Starting as

a humble poet I

quickly climbed to the

top of my profession

assuming a position of

leadership and honor.

It is right that a

woman should call

me out now. Yes,

I am a Kennedy.

And I await

your orders.

You are the New Americans.

The homeless are wandering

the streets of our nation's

greatest city. Homeless

men with AIDS are among

them. Is that right?

That there are no homes

for the homeless, that

there is no free medical

help for these men. And women.

That they get the message

—as they are dying—

that this is not their home?

And how are your

teeth today? Can

you afford to fix them?

How high is your rent?

If art is the highest

and most honest form

of communication of

our times and the young

artist is no longer able

to move here to speak

to her time…Yes, I could,

but that was 15 years ago

and remember—as I must

I am a Kennedy.

Shouldn't we all be Kennedys?

This nation's greatest city

is home of the business-

man and home of the

rich artist. People with

beautiful teeth who are not

on the streets. What shall

we do about this dilemma?

Listen, I have been educated.

I have learned about Western

Civilization. Do you know

what the message of Western

Civilization is? I am alone.

Am I alone tonight?

I don't think so. Am I

the only one with bleeding gums

tonight. Am I the only

homosexual in this room

tonight. Am I the only

one whose friends have

died, are dying now.

And my art can't

be supported until it is

gigantic, bigger than

everyone else's, confirming

the audience's feeling that they are

alone. That they alone

are good, deserved

to buy the tickets

to see this Art.

Are working,

are healthy, should

survive, and are

normal. Are you

normal tonight? Everyone

here, are we all normal.

It is not normal for

me to be a Kennedy.

But I am no longer

ashamed, no longer

alone. I am not

alone tonight because

we are all Kennedys.

And I am your President.

Eileen Myles, "An American Poem" from Not Me, published by Semiotext(e). Copyright © 1991 by Eileen Myles. Reprinted by permission of Eileen Myles.

Do you value the examination of the political in poetry? If so, what experience(s) taught you its importance?

I think I learned from observing, when I was young, the impact of my friend Allen Ginsberg that poetry both propelled a poet to a unique kind of prominence by virally charging the culture around him/her by the skill of their assertion of not even necessarily "the political" but by describing in their work (and their life) what was urgent to him or her and through that finding out pretty quickly how supremely political that action was and is. I didn't think I had access to the political in my own work for quite a while. It was there but it wasn't really a force. When I did write such a poem, when the poem and myself began to stand in a new world because of the action of the poem I saw the power of language like I never had before. And I only wanted to repeat the experience. I think poetry is always political but when you've really stepped in it you know it because the world moves around you in a way.

If you write about politics frequently, what issues, difficulties, advantages and disadvantages do you negotiate? Which poets do you draw on when conducting such negotiations?

Not everyone will like it, publish it, reward you. But you will find out very quickly what you're culture is. And it will keep coming as long as you put it out. I draw on everyone. Allen, of course, and Lucille Clifton, and Hart Crane. And James Schuyler. Work that I feel is political is not necessarily work that clocks you over the head with it. I mean I like that too. Amiri Baraka. Judy Grahn. Walt Whitman.

What 'responsibility' does an artist have to artistically engage his or her own politic?

I think you're talking about being responsive. I pray to always be responsive but I often fail. I think it's part of being an organism, this responsiveness. It's not an edict from the outside. People obviously duck shit in their lives and their work but I think by and large people are responsible. We might just not like how they respond. Or what they are responding to.

In 2008, Horace Engdahl, the secretary of the Nobel prize jury, wagged his finger at American writing saying that "[American writers] don't really participate in the big dialogue of literature. […] That ignorance is restraining." What do you think? How have recent American poets engaged with or neglected the so-called 'big dialogue' of literature? Is this 'big dialogue' a political one?

He doesn't know what it's like to be American. We'd like him to tap his friends in the other department to give Bradley Manning the Nobel peace prize. Then he can talk about us. He should help us first. Then he can talk.

Is there room for romantic or rugged individualism in political poetry (as opposed to a capacious perspective of Whitman or other past poets)? If so, where is its place?

Oh I think these two are conflated.The romantic and the capacious. Whitman and the rugged individual. I think there's always a place for everything. It's like looking for an audience. I think of Martin Luther King's line: there is no right time. There's also no right place. So we must move around and find it or else do something else.

Where do you draw the line between poetry and propaganda? What is the purpose of such a line? Should today's poet be concerned with editorial censorship?

I think one person's propaganda is another's poem. it's an impossible line. It's a social one and there's so many societies. I think the purpose of the line is censorship. I think we're tremendously affected by what people don't want to hear. And I think our power is inherently displayed in the choices we make around that. I mean you have to pick your battles. I love to say things about other poets and work I hate and I love to tout the work of those I love - for their work. But sometimes I think, or increasingly that in this climate we have bigger fish to fry. I think post-literary might be the way to go. To be writing for larger worlds with larger struggles. So that infighting and branding and ambition aren't flavoring all your utterances. Propaganda against the proper enemy is probably exactly the poem I'd like to write. But it still might be a very subtle thing. Very quiet and small. I always think of this poem that James Schuyler wrote when Ted Bundy was put to death. He described a tree in a landscape that was struck by lightning and he dropped the line "may god forgive them" in the poem. He said that originally he made it very clear who or what the poem was about but finally he took that out. I think it's a stunningly political poem for merging the fate of a man and a tree. It's monumental political poetry. I don't think I'm just being perverse nor was he.

What are your thoughts on shifts in the state of the political voice in contemporary poetry, from the early modernist to the beat poets and black arts movement, to today? Where are we now? Where are we going?

I think people are hungry to be heard. I think poems are increasingly ads for discontent and should be. We are calling out for help.

Hey and by the way...there is a OWS poetry anthology that needs support in order to get published. Here's the link. Help them!

* * *

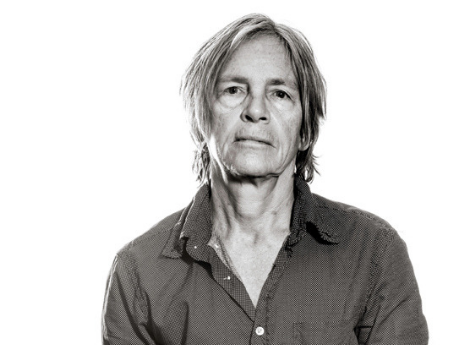

Eileen Myles was born in Cambridge, Mass. in 1949 and moved to New York in 1974 to be a poet. She has published more than twenty collections of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, plays and libretti including Sorry, Tree, Chelsea Girls, Not Me, Skies, The New Fuck You/adventures in lesbian reading, Cool for You, The Importance of Being Iceland: Travel Essays in Art, for which she received a Creative Capital/Warhol Foundation art writers grant, Inferno (A Poet's Novel) which won a Lambda Book Award and most recently Snowflake / different streets (Wave Books, 2012). She's a 2009 recipient of the Shelley Prize from the Poetry Society of America.

Published September 2012