Q & A: American Poetry

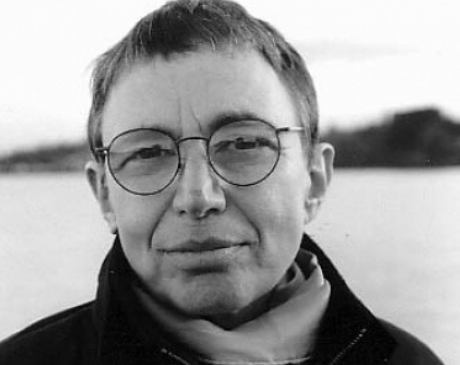

Q & A American Poetry: Marilyn Hacker

What's American About American Form?

It is, to me, an obvious remark that all poems are "formal": the writer's decision to arrange a piece of writing on a page with line and stanza breaks which do not correspond to the page's margins creates an implicit and fertile tension, a counterpoint, between the rhythm and pacing of the poem's syntactic structure and that of the visual (and aural, metric) structure created by the poem's typographic setting—a tension which seizes the eye, but can also be heard, often enough, when the poem is read out loud. A line in a poem which ends with the verb "lies," with the following line beginning, say, "beneath the surface," cannot avoid suggesting both meanings of that verb. Alternatively, a poem with a strong accentual meter (whether or not it is one to be found in manuals of prosody) can be "heard" as a poem even if it is printed out as prose, and the interplay between meter and syntax will be perceptible, as W.E.B. DuBois and Hayden Carruth have both proved to readers.

But that's one take on what is "poetry" about "form," or what is "poetry" tout court, not what's "American." American poets writing in English, whether they be from the United States or Canada, stand at an intersection of many formal traditions, including the indigenous poetries of Native Americans, the call-and-response forms enslaved Africans brought with them to this continent, which they married to English ballad and hymn forms to create both spirituals and the blues, the continual proximity of Latin American poetry, and, of course, the variegated English language prosodic tradition and its antitheses which came to this continent with the English settlers. That tradition did not remain purely "English" or British for long, as is witnessed by the career of Phillis Wheatley, the brilliant child from Senegal, who was writing verse in forms she learned from reading Alexander Pope and Thomas Gray six years after she was taken from a slave ship in Boston, not speaking a word of English, her age—six or seven—determined by the fact that she was losing her milk teeth. The significance of Wheatley's adoption of English meter can bear much discussion—but so can the fact that the rhythms of John Milton's verse and prose informed the cadences of African American religious rhetoric through the early decades of this century, and can be heard echoing in pulpits today. One thing Wheatley's brief and tragic career signally exemplifies is that few American poets stand in the same relationship to the prosodic and other traditions of English verse as even the most politically or artistically radical British writers. All of us who are not Native Americans are immigrants, or the granddaughters or great-great-grandsons of immigrants, likely to have ancestors who, like Phillis Wheatley or Olaudah Equiano, if under less duress, adopted English out of necessity. Many American poets grew up with the echoes and cadences of another language as background to their English. Just as, at least in New York, the quintessential American foods are pizza and the bagel, and the quintessential American music is jazz, the quintessential American locution is ein bissel Yiddish y un poco Latino, and sounds a bit ebonic on the phone. The sonnet on the base of the Statue of Liberty was written by a young Jew of Portuguese descent, Emma Lazarus. It's not surprising that John Berryman had a blackface double, Mr. Bones, in his "Dream Songs," that Elizabeth Bishop wrote a suite of "Songs for a Colored Singer" in honor of Billie Holiday; nor that Gwendolyn Brooks adopted the persona of the white Mississippi housewife whose complaint led to the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till—and gave her the same destructive romantic illusions as the black teenage protagonist of her domestic W.W. II mock-epic, "The Anniad." As Toni Morrison has pointed out, the constant presence of a racialized Other, sometimes a racial alter ego, is deep-rooted in American writing. But it is, I think, rooted in the American language as well. Along with the metrical/ syntactical tension which characterizes any poetry, American poetry is distinguished by another tension, between the mestizo American language and the written poetic traditions it inherited more from the English than from any of its other tributaries.

But—and this is an instant "but"—almost every verse form associated with English prosody comes from somewhere else—the sonnet from Italy, the sestina from the lingua d'oc, the villanelle from France—even blank verse was introduced in the 16th century by Thomas Wyatt and the Earl of Surrey, from an Italian model. I'm not sure if any form other than Anglo-Saxon accentual verse is truly indigenous. And this is only congruent with the cheerfully mongrel nature of the English language even preceding its American expatriation, including, as it does, words of Anglo-Saxon, Latin, French, Spanish, Arabic, Greek and German origin, seeming surprisingly ready to integrate, if not embrace, neologisms. We do not have an Académie anglaise, still less an Académie américaine, to vote on the acceptance of "knish" or "dreadlocks" or "megabyte" into the dictionary. And that is one thing, in a personal parenthesis, which makes the writing of metered and rhymed poetry in English such a pleasure—the juxtaposition of those Latinate, Anglo-Saxon, and other-flavored words, "chickenshit" and "hematocrit," "morose" and "Mykonos," "contextual" and "transsexual," "marathon" and "maricón," "dental floss" and "meshugass." That kind of juxtaposition is perhaps most flamboyant when it involves rhyme, but it is also characteristic of American poetry in unrhymed forms and freedoms. Perhaps the American romance with technology, only briefly chilled by the enormities of Hiroshima and Auschwitz, has made American poets open to acquiring yet another vocabulary, another set of forms: I think of May Swenson's "shaped" poem describing the physics of wave motion, which also describes, without a word extraneous to the stated subject, sexual excitation and release; of Rafael Campo's sequence "Ten Patients And Another," stretched on the grid of two fixed forms, the sonnet and the patient history every medical student learns painstakingly to take.

American poets seem to have a propensity to invent forms; our very characteristic contentiousness on the subject, going back to Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, is also the sign of an extreme attention. Dickinson's secular transformation of hymnal measures was as deliberate a gesture of prosodic innovation as Whitman's rolling cadences—especially when we remember that Dickinson had Elizabeth Barrett Browning's feminist blank verse epic Aurora Leigh virtually by heart. Her decision to avoid the pentameter and to privilege a "popular" measure may not have been a consciously defiant one, but was nonetheless momentous for the history of American prosody, and perhaps not unrelated to the subversive appropriation of Gospel cadences by enslaved Africans. While literary Modernism in the English language novel had British and Irish sources—James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, Dorothy Richardson—Modernism in poetry had American parentage. (Though upon at least one of the frequent occasions when Ezra Pound campaigned for "breaking the back of the iambic pentameter," his next counsel was to "write Sapphics until they come out of your ears"—that is, to learn to hear a metrical music unfamiliar to American English.) Marianne Moore, that quintessential Modernist, hardly ever wrote a poem which was not "formal"—but the forms were always of her own invention, elaborate fixed syllabic stanzas whose metrically irregular lines were visually marked by placement on the page, and often aurally marked by rhymes, with the rhetorical superstructure of the fable.

On the subject of Modernism, it is important to remember, in a cautionary way, that one of its projects, less laudable in my eyes than "making it new," was to separate poetry from a populist or popular audience, those "women's clubs" Pound scorned, but also factory workers of both sexes, businessmen, farmers, bookkeepers, high school students and their teachers. It's arguable that the lack of critical consideration received by the work of Edna St.Vincent Millay, a decline in "reputation" which began well before her death in 1950, has as much to do with a devaluation of the work of any poet who appealed to a popular audience as with her feminism or use of received forms. In this respect, the work and the aesthetic goals of African American poets from the Harlem Renaissance through the present provide a welcome corrective: their concern seems to have been to bring a linguistically and politically complex poetry to as wide an audience as possible, both within and beyond the black community. The Crisis and Opportunity, where so many of the Harlem Renaissance poets first published, were the journals of the NAACP and the Urban League respectively, and they explicitly served a readership broader than a purely "literary" one. Decades later, this poetic "reach" would continue in the work of writers associated with the Civil Rights movement, the Black Arts movement, the anti-war movement, and the women's liberation movement.

The American poets of the generation preceding my own who continue to mark my own work were—and are—innovators more interested in how formal transformations illuminate and forefront previously unexamined or marginalized aspects of life and language than in preserving or revising poetic form for its own sake: I think of Muriel Rukeyser's incorporation of the legal testimony of strip- miners with silicosis, or of the syntax of a refugee child learning English, into poetry, of Hayden Carruth's demotic Vermont and upstate New York dramatic monologues, his Horatian syllabic meditations drawn on the unforgiving northeastern landscape, of Gwendolyn Brooks' Jacobean syntax limning the portrait of an African American community—the south side of Chicago in the aftermath of World War II—with respect, verbal and sensory virtuosity, and ludic irony.

Americans have, as Robert Pinsky has reminded us, an indefatigable appetite for self-definition. This is a nation with a contradictory past, a past with very different resonances for its different citizens—the African American great-great-grandson of slaves and a man who owned slaves, the Boston Irish bus-driver's daughter applying to Harvard, the Polish Jew whose parents were the sole survivors of their shtetl, the Vermont hardscrabble farmer losing the battle against agribusiness and rural gentrification. It is a culture still engaged in inventing itself, so it is no surprise that such invention should also be a tool, if not the central project, of its poetry.

Published 1999.