In Their Own Words

Sydney Lea's “Abattoir Time”

Abattoir Time

The widower pushed the tailgate shut and fell.

The two sounds –click and thud– seemed synchrony,

As if one in fact were function of the other.

The red calf, bound for veal in the pickup's bed,

Looked rearward over his shoulder. No one there.

A ginger-hackled rooster, framed by the door

Of the loft, screamed loudly, sun igniting him

To noontime flame. He sent six hens in a dash

For cover under bush and sill, as though

His love-assault might be a thing far worse

Than the farmer felt – or rather did not feel,

The death so quick and commotionless his livestock

Didn't notice. Everything once had purpose

Here, and meaning, and might still have, if only

He'd stayed to read them. Now a skinny cloud

Rode unremarked on a breeze above the barn,

Unsafe and leaning. His horse, a spavined relic

From other ages, whickered behind the house,

All canted too, its paint mere scattered flakes.

Meaning and purpose had blurred in recent years

But the farmer kept right after them no matter.

Who'd free the weanling now, who lead him to slaughter?

All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

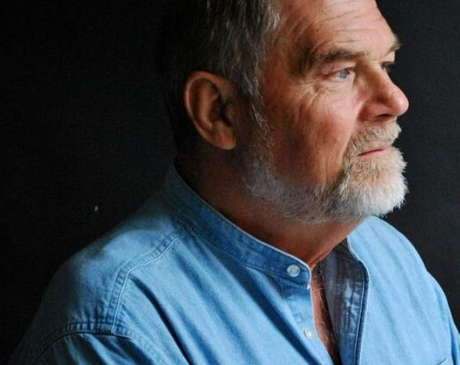

On "Abattoir Time"

It's funny how poems tend to get generated in my mind. They never begin with what, in my teaching days, students called "ideas." Rather, they begin with some sensory recall, more often than not auditory. This can be the sound, say, of a certain woodpecker on a very still spring morning; a snatch from an old Monk tune; or, as in this case, a small chunk of conversation that has lodged itself in mind, whether or not I knew it had.

A few months back, someone told me that a local Vermont farmer – one whom I didn't know well and one who, like all small farmers in the era of agribusiness, had been struggling to keep his place going – had just dropped dead while closing the gate of his pickup on a veal calf.

I somehow instantly imagined the click of the gate and the thud of the man's body when it fell.

And then my mind unaccountably shot back some fifty years to a Pennsylvania farmer whom I knew a lot better. He had lost his wife and, age supervening, had been finding the relentless labor of farm life more and more taxing. He said to me, a man not yet twenty, "This place used to have a meaning and a purpose." The click and thud instantly married that remark, and I fused the two countrymen into one. I had only to fill in the physical details of the north country farmhouse and farmyard to finish the poem. Whatever its merit, it was all but given to me.