In Their Own Words

Kerri Webster on “Vanitas”

Vanitas

Striated stones returned to the wrong river, blue house

falling into the sun, the systems refusing to be allegory—

when I was fully present I thought presence would

kill me, vines forcing through windows and the soul-

sucking slowing of time when I broke inside. Here

is your weighted blanket, here is your poppy, I know

a woman just waiting for elegy to show up in her brain,

alive only for that, and then she can go. I pretend

form will save us, worry about how much the reiterative

soothes me, stones lined on the sill so my mind

stays still in this realm. Here is the landmass tattooed

on my body, here are the flowers we've planted

to cover up what we've done, creeping myrtle, creeping

phlox, creeping thyme, none of this easy, what with

the man shoving the girl's face into the ground,

what with the world burning down, creeping alyssum

shock-yellowing the yard, sea of stems pinning down

absolutely nothing. Daily I wake inside expiation's

failure, bee brooch pinned to my breast instead of

a cross, testament to the foolishness of placing pleasure

before all we could not bear, our souls the color of

propolis but our monkey hearts marbled with folly.

The way a command can also be a plea: Fuck me,

the imperative our truest tense because who doesn't want

to top from bottom, really, rule and abdicate

all in one breath? I know a widow who didn't make

love for ten years, slow death my mind can't grasp,

glancing then glancing away. The air tastes of sugar and

my hilly body's one hell of a gateway and when I first

saw the statue of the great god Pan, I wanted very much

to mount him, lick that sweet spot where pelvis meets

furry haunch. I gray splendid, I come in palms, and

I would never, ever be a girl again, despite all the years'

terrible knowledge. We move through these long last days

touched, which is to say fingered, which is to say moved,

which is to say mad. The stranger carves a gold tunnel

through the gold book. The river faces up neon, glows and

glows. I set my glasses by the bed, walk the river path.

Show me the gold tunnel. Show me where the gold tunnel goes.

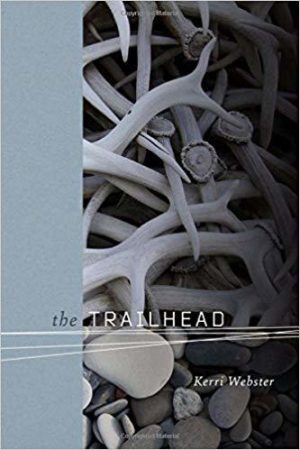

From The Trailhead (Wesleyan, 2018). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Vanitas"

A vanitas isn't a vanitas if it's just the skull; it's the juxtaposition of bone and beauty, often ruinous beauty, that creates the discourse. In "Vanitas," then, many magpied details: a stunning statue of Pan in the St. Louis Art Museum, the weighted blankets used to calm anxious humans, the Idaho tattoo my siblings and I got on our mother's 70th birthday, a bee pin I saw at a pawn shop, a very real twenty-mile river path that runs along the Boise River, and an imagined tunnel I don't yet understand.

There was a moment, it felt like, when everyone was talking about being more fully present as a path to contentment. I'm not advocating oblivion—I've courted it, and it wasn't pretty—but what strikes me when I hear talk of "presence" is that, as "Vanitas" says, "when I was fully present I thought presence would/kill me"—that the times in my life when I've felt most alive have been times of crisis, times of amygdala and adrenal overdrive, times when time itself slowed down to a nearly unendurable crawl—the year cancer ate my mother's body, for example, until morphine released her from presence. I'm wary in general of things that fall under the umbrella of "self-care" because they're so often a function of privilege and, very specifically, a way to get white women to see themselves as monetized projects and spend /schedule selfhood accordingly. To be truly present is an ethical imperative, not a purchased luxury, and it hurts, often to the point of shattering. I'm writing this in a week in which the presence of 2,000 children was reduced to the pinpoint terror of their parents' absence, and many of us made ourselves listen to the audio of their cries. It took me a full day to make myself click on that. "Vanitas" explores the desire to look away, the desire to numb after looking, the desire to lose oneself in desire or beauty, and the cognitive dissonance created at the intersection of moral imperative and human failing.