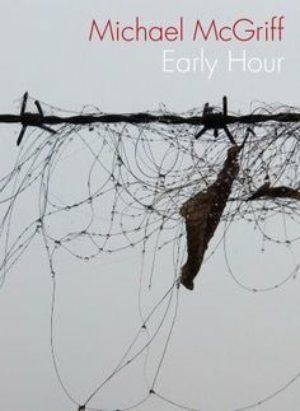

In Their Own Words

Michael McGriff on “Early Hour”

Early Hour

In the early hour.

In the hour of copper.

In the secret minutes

coiled around wooden spools

and scrawled into the sill dust

beneath our open window.

In this room lit up

like the throatlatch

of a horse, like sea-foam

under the breeze of a black moon.

You are asleep, the dog

collapsed between us,

the shadows across your stomach

umber-flecked and swimming

toward some vague memory of blue

that the early hour

has wrung from its hair.

Your breath smells of farriers' hammers,

of April spreading its sheer fabric

among the first blooms

of the dogwoods.

The edge of the floodplain

is a red crescent

and you shimmer

like an ax-head lost in the creek.

When the whereabouts

of the azaleas

become uncertain,

the outline of your face

is sky-written in the black loam

of the thunderheads.

When Cygnus scrapes his iron beak

against the rafters,

when the cathedrals

in each whitecap

cross the river,

when the dog's skull

fills with green light

and a bucket of sparks

empties onto the mantle-dark

shoulders of this early hour,

you become the early hour.

You become water

dressing up as the opposite

of bone and rags,

you become an island

filling with reeds,

the shore wind repeating itself,

the sound of two feathers

crossing one over the other

among threads of dust.

You sail past the dead

with their saffron-yellow teeth,

their gristmill jaws,

and their wings clipped back

to callused nubs.

In this early hour

I hear a rustling

in the dogwoods,

the sound of a table

being set, a deck of cards

sliding across

the crushed lip

of its box.

I hear the rail yard

draw an arrow

to the edge of our country—

and though there are no trains,

a few dogs run mad beside them

through the tall,

impossibly blue grass

as you drift within your body

and into an hour as nameless

as the stone heart of a plum.

From Early Hour (Copper Canyon Press, 2017). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "Early Hour"

In 2014 I encountered a painting in the Portland Art Museum's permanent collection that changed me, Frühe Stunde (Early Hour) by the German Expressionist Karl Hofer. This oil painting depicts two lovers in bed, and it seemed, at first, rather unremarkable. It looked to me like any one of numerous European paintings one might whisk by in a state of museum-fatigue while bounding toward marquee exhibits and brochured galleries. The closer I got to Hofer's painting, however, the more nuanced and striking it became. The male figure in bed (nude, propped up, awake) suddenly took on a sickly aura, and whatever world the female figure next to him (nude and asleep) was about to re-enter when she woke up became one imbued with the suggestion of decay. This painting is a work of tension and suspension, and in many ways anxiety and ecstasy are two of its forces. It insists on multiplicity. It rejects the binary. The figures become an erotic hinterland between the known and the apparitional, the living and the dead. No part of the body is mere detail, no detail mere backdrop. Everything is a conduit for meaning, from the skeletal trees in the deep background to the oddly placed curtains in the foreground to the dog curled up and sleeping at their feet. Nothing is as it should be, yet everything appears organic to its sensual moment. What sharpens Frühe Stunde are its historical markers—it was painted in 1935, in Germany. Through this lens, the canvas becomes deeply ironized and ultimately prophetic; it becomes a suggestion of future horrors.

Hofer's works would go on to be derided by the Nazis and showcased in the Reich's so-called Degenerate Art exhibit in Munich in 1937. He would paint in secret throughout the war. The fact that I am alive and can be a witness to his art changed me in a way that no other art experience has. I'm grateful to those hands that kept this work safe, sacred, and alive.

My poem "Early Hour" begins a book-length meditation on the intersection of the erotic, the surreal, and the images of place. Hofer empowered me to triangulate my sense of Eros with my penchant for the surreal and with my fear that our modern world is teetering on the edge of something abject and sinister.

With Neo Nazi marchers recently on the University of Virginia campus chanting "blood and soil"—the very ethos behind the 1937 Generative Art exhibit—and with a President structuring his rhetoric into nuanced endorsements of white supremacy and militant nationalism, Hofer's work continues to inspire and threaten. It threatens those who believe art should serve as an iron wing of the state. It gives power and a voice to those of us who have committed our lives to individual expression, be it a time of peace or violence.