In Their Own Words

Kiki Petrosino's “This Woman's Face is Your Future”

This Woman's Face is Your Future

I, too, have hated it. Something off about the teeth. Long & long, I've studied on its shape: dumb as domett. Dulsome as Dallas ditchwater. Lantern-head, I've said. Happy horsebag, too bad to bleed. Just wanna iron shut its mouth from hem to hem. Wanna break the nose down to a hawse-hole. Could I gag it out? Once gagged, I mean, with long dry coughs of hair. Could I shutter it with one quick knot to the nape? Snap it off in my hands? Old blister pack, old zit. In my cabin, I'd snag that thing on the first nail. Keep pulling it down & down by the jaw. Yes, & let them shreds hang lovely in the lamps. Only then would I give up awhile. Put on my sea-gown & rise, beautiful on the dark decks.

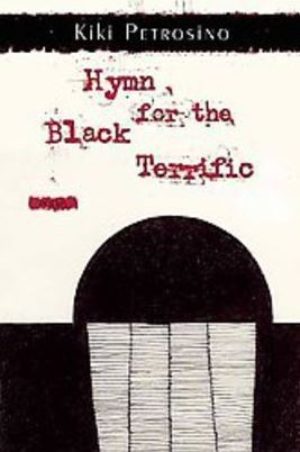

From Hymn for the Black Terrific (Sarabande Books, 2013). All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

On "This Woman's Face is Your Future"

This poem began with its title, which emerged for me in the last few moments of a dream. The whole sentence surfaced at once, like a seashell revealed at low tide. My dream, as I remember, was an anxious one. I had to assemble an object composed of tiny, elaborate parts—screws and gaskets, a loose pile of flat washers that, maliciously, began to disappear when I grasped them. There was a sense of doom about the whole enterprise; somehow I knew that I wasn't going to finish my task. The reason (which I seemed to hear in the voice of a dream-narrator) was fundamentally connected to me, as a person. The sentence, "This woman's face is your future," came to me like a moral from one of Aesop's fables. And in the seconds before the dream faded, I remember feeling a combination of disappointment, resignation, and peace. I decided the dream had been leading up to this idea: I was the thing I had to accept. The tedious construction project that had occupied me for so long was just a distraction from this more important struggle.

Like many American women, I've spent way too much time comparing my face to those of others, and finding myself lacking in fundamental beauty. The self-imposed court trial of my adolescence resulted in a series of head-to-toe guilty verdicts for which I'm still serving my sentence. What's more frightening than a mirror in the morning? Too many of us stand convicted in our own minds, approaching our faces with tweezers, mascara, and a plan: revise, revise, revise. In consideration of this, I borrowed Marianne Moore's opening line from "Poetry" to launch my own exploration. Moore begins by conceding to the reader: "I, too, dislike it," a sentiment that puts her on the reader's "side" by critiquing poetry that flaunts obscurity for fashion's sake. The thirty-eight line version of Moore's poem establishes the ideal shape of her poetics, one that acknowledges the power of language to connect imagination with lived experience. Her "imaginary gardens with real toads in them" embody this ideal. These toads can attain "reality" due to the sheer force of the artist's imagination. For Moore, they are "genuine" because they can live, tangibly, in the garden of a poem without being embellished or distorted by the poet's need to make clever symbols or perform gratuitous rhetorical tricks. In other words, Moore's ideal poet empowers her creations to live toad-lives within her poems; she does not crouch in the garden herself, wearing a toad-mask.

In the mirror, my face appears imperfect. More than that: it appears as an imperfect reflection of the self I mean when I say I. But intellectually, I know that everything I believe about physical beauty is a cultural construction. Even when I'm judging my mirror-image most harshly, I can feel the rubber bands from my judge-mask pressing against the back of my head. I know, too, that the pronoun I doesn't stand in for "the body." So when I say "I" in a poem, I'm just wearing an I-mask. As a poet, there comes a time when you want to break all of these constructions "down to a hawse-hole" and view the shapes inside, however ugly or strange they may be. The questions that occupy the central portion of my poem ("Could I gag it out…. "/ "Could I shutter it…") try to address this impulse to reveal the truth of selfhood, not by revising its definition, but by cutting off the harmful rhetorical vasculature that feeds our collective dysmorphism. For me, this work takes place "in my cabin," the deep interior of my own imagination. Only there, where language collides with experience before emerging as a poem, can the I-mask take a proper shredding.

The poem concludes with my take on a moment from Act V of Hamlet, in which Hamlet, harried by bad dreams, emerges from his own cabin, "scarf'd" in his "sea-gown," to replace the sealed letter ordering his execution with one calling for its carriers, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, to be put to death instead. Writing the second letter doesn't just revise the first. It effectively replaces one future with another, bodying forth "a new commission," as Hamlet explains to Horatio. In Hamlet's case, as in my own, this self-authored future is still deeply imperfect; it is, by nature, subject to deep, often uncomfortable, examination. It's dangerous work. As Moore herself proved when she pared "Poetry" from thirty-eight lines down to four, the artist's impulse to dismantle is so strong that it can sometimes lead us away from truths we've already revealed to ourselves (and to our readers). But for now, I'm pleased when I can feel the "dark decks" of my poems shift under my feet. It means there's still a chance to un-build what I've made, even if I refuse to take it.