In Their Own Words

Jackson Mac Low: Lines–Letters–Words

Jackson Mac Low was born in Chicago in 1922. He is best known as a poet, but he was also a seminal and influential figure in the avant-garde visual arts, performance, theater, film, dance, and music worlds beginning in the 1950s. He influenced and was associated with a wide range of movements, including the New York Fluxus movement, and he collaborated with artists, poets, and institutions throughout his career, most notably The Living Theater (Judith Malina and Julian Beck), Judson Dance Theater (Trisha Brown and Merce Cunningham), David Antin, John Cage, Simone Forti, Allan Kaprow, Meredith Monk, Jerome Rothenberg, Tui St. George Tucker, Yoko Ono, Diane Wakoski, and La Monte Young.

I first met Jackson in 1990, when he was the Regents' Lecturer at the University of California San Diego, where I was an undergraduate studying philosophy and poetry. At that time, I was part a group of poets and performers that had founded) 39, a magazine/chapbook that published chance-generated texts, concrete and Xerox poetry, group-written poems, and collaborations between writers, musicians, artists, and filmmakers. His "quasi-intentional" or "diastic" methods for composing poems—which almost always consisted of a transformational system for choosing word fragments or whole words from charts or source texts—called into question issues of authorship, control, and authenticity. At first glance, his poems are jarring and seemingly impossible to decipher, but upon closer reading of accompanying descriptive texts that painstakingly describe the conditions and processes of composition, a reader can begin to understand the deeper structures that hold these works together. For me, Jackson's poems were courageous, extreme, difficult, and revolutionary, and they opened the door to work outside traditional subjective, expressive, and emotive confines of poetry.

Being able to hear Jackson, his wife and collaborator Anne Tardos, and musician Charlie Morrow read and perform live during his residency on campus was a profound experience. Jackson's guest lectures in Jerome Rothenberg's experimental poetry class provided a second important and lasting impression. Jackson first talked to us about how his own pacifist-anarchist-Buddhist philosophy influenced his work. This was the first time that I encountered an artist who self-identified as an anarchist, a position that allowed for "getting out of the way" in order to permit other people to make their own decisions while reading or performing within the framework of his texts. Jackson then conscripted us into learning how to read and perform some of his "Simultaneities," which included Drawing-Asymmetries, Gathas, and Vocabulary works. We spent several hours with Jackson going over his very specific performance instructions for each type of work, and then we were given typewritten or hand-drawn works to enact. Things progressed slowly. Jackson was not happy with our first attempts. Because we were not listening to one another, what resulted was a cacophony of spoken letters, phonemes, and words. He asked us to think about the spaces between the letters, the visual layout of the poem, to hear the ambient noise outside of our classroom, and finally to be present and aware of all other performers. Probably by the fourth or fifth time we tried to perform the works, we began to understand and develop strategies for group reading that both followed his rules and allowed us more agency to produce increasingly interesting and interactive results.

Since my early interactions with Jackson at UCSD he has remained a significant and influential cultural figure for me. About two years ago, I decided to reach out to Anne Tardos to see if I could visit her, look at Jackson's archive, and discuss the possibility of organizing a show for The Drawing Center. I was specifically interested in his early drawings, collages, and hand-drawn performance scores like the Drawing-Asymmetries, Gathas, and Vocabulary works, which had been documented by Steve Clay in the 2005 Granary Books publication Doings: Assorted Performance Pieces 1955–2002. I wanted to explore in more depth how drawing influenced his thinking. Over the past fifteen years, I noticed some of Jackson's works were included in visual art exhibitions, indicating a growing interest in his work beyond the confines of the poetry world.[1] Anne graciously allowed me to see some of the drawings in the many archival boxes that Jackson left behind in the loft on North Moore Street in Tribeca after his death—what a treasure trove they turned out to be!

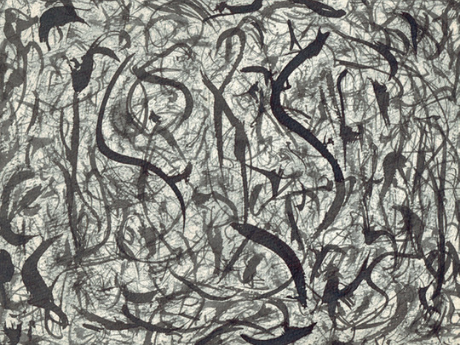

Jackson began drawing in his early teens and continued to create visual work throughout his life. The earliest abstract automatic drawings in this exhibition were created between 1947 and 1953 with gestural ink brushstrokes in sketchbooks or on single sheets of paper. Jackson's indebtedness to artists like Jean Arp, André Breton, Salvador Dalí, André Masson, and Joa Miró, all of whom pioneered Surrealist automatic drawings in the 1920s, is clear. His early drawings, with their loopy lines and non-representational forms, were explorations into the use of chance and non-systematic compositional techniques; he had already been studying D.T. Suzuki's writings on Zen and Kegon Buddhism in the early 1940s, and was familiar with practices and methods to release the mind from conscious influence. In 1948, Jackson attended a John Cage concert of Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano at Columbia University. This composition was chance-derived and used Cage's prepared pianos to further remove the creation and performance of the work from the systematic rules and tunings of Western music. Jackson was intrigued by Cage's methods, and surely hearing his music inspired him to continue explorations with drawing into similar territory.

In 1953, Jackson shifted his focus from abstract drawings to drawings that contain fragments of letters and in some cases, full words. Untitled (September 10, 1953), Pie (n.d.), Ape (n.d.), and Hi (n.d.) represent the first time that Jackson's drawing concerns intersected with his radical ideas about poetry and performance. These are the earliest examples of Jackson's drawn performance scores, and it is possible that George Brecht, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Toshi Ichiyanagi, or Allan Kaprow, who were enrolled with Jackson in Cage's experimental composition classes at the New School between 1953 and 1958, helped to realize some of these. We do not have performance instructions for these works, but the rules published in 1961 for performing Drawing-Asymmetries indicate that line thickness and font size are meant to guide duration, silence, intonation, and pitch. These drawings made between 1947 and 1953 are critically important to understanding Jackson's oeuvre. They illuminate Jackson's early developments and were foundational for the deeper philosophical and political ideas that led to his now better-known radical writing methods. It was not until between 1954 and 1955, nearly seven years after Jackson began creating automatic drawing experiments and hand-drawn scores, that he published the 5 biblical poems, the first typed collection of his non-intentional writing and "simultaneity" performance instructions.

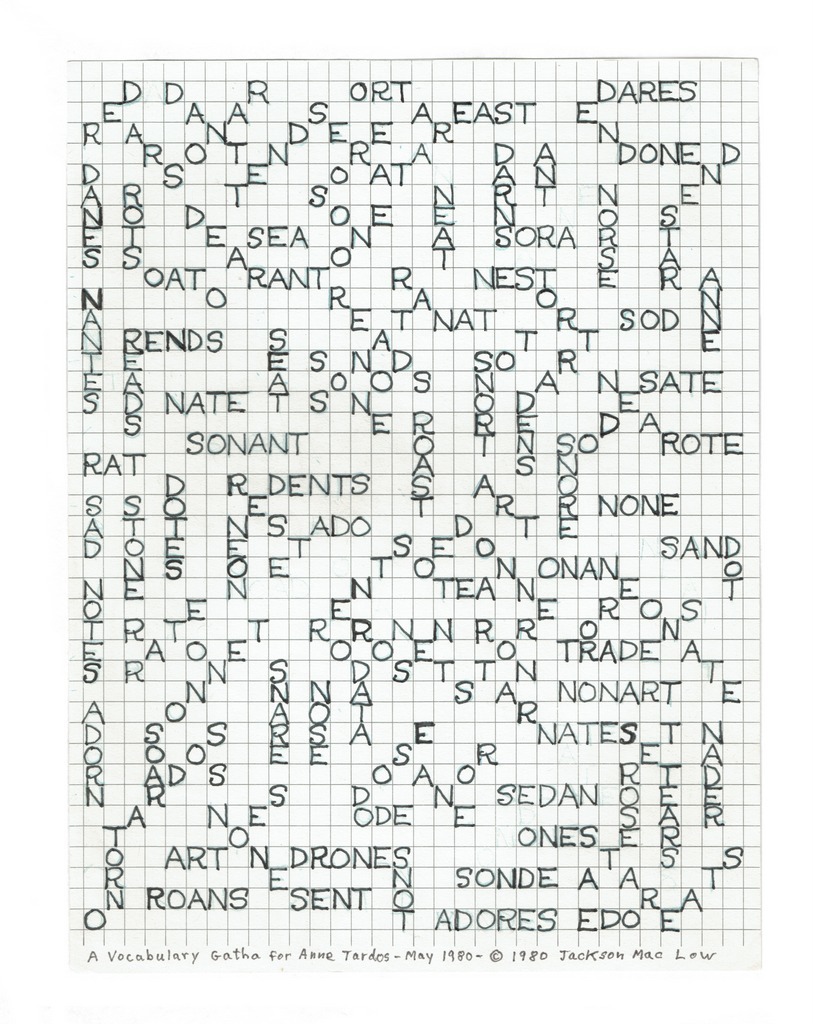

In 1961, Jackson composed the script for Tree*Movie, although the film was not made until a decade later in 1971.[2] I have included the film in this exhibition, because 1961 was another pivotal year for Jackson's visual output. Tree*Movie is a prototype for the static and structural filmmaking later popularized by Hollis Frampton, Paul Sharits, Michael Snow, and Andy Warhol. Tree*Movie brings together Fluxus's preoccupation with imperative actions and Jackson's tendency to merge language with more expansive visual thinking. In 1961, concurrent with the development of the Tree*Movie script, Jackson began to make Drawing-Asymmetries, Gathas, and a drawing entitled Om in a Landscape. For the Drawing-Asymmetries Jackson began by randomly choosing a "generator" word from an existing text and writing this word on a blank sheet of paper. He would then write a series of words, each of which were acrostically connected to the generator word. These haphazardly placed, differently sized, and sometimes distinctly colored and hand-drawn words construct strong visual compositions, which are not representational, but performative.[3] The equally visual Gathas, the Sanskrit word for "verse" or "hymn," consist of individual letters, which are drawn omnidirectionally on graph paper. While Jackson's earliest Gathas were derived from Sanskrit mantras, later Gathas include words sourced from modern texts, such as Kathy Acker's 1978 novel The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula. These drawings are examples of what Jackson described as Buddhist performance scores that "encouraged performers and hearers to give 'bare attention' to the letter-sounds, words etc."[4]

In 1973 Jackson started to make Vocabulary drawings by handwriting proper names in India ink on large sheets of white paper. Jackson would then write any word that came to mind that included one of the letters from the name. In the performance instructions for these works, he included specific rules for musicians and vocalists, adding to the phonetic connotations of each word by positioning them as tonal notations. In The Drawing Center's exhibition, there are several important Vocabulary drawings including A Vocabulary for Peter Innisfree Moore (February 1974–July 1975) and Stephanie Vevers (August 1977). In 1979, Jackson created the Skew Lines drawings, which act as scores for vocalized actions. Each Skew Lines work consists of differently colored, slanted pen lines that span across a white page. According to Tardos, Jackson rarely performed these works, and so they have not been published or seen until now.

Starting in 1977 and continuing until 2004, Jackson also made a series of "name" drawings that Anne calls "Occasional Poems." Jackson began each of these works on a specific occasion, such as the birthday of his daughter (Clarinda) or of his wife (Anne) or to celebrate Valentine's Day or the New Year. These drawings, which take the words of the celebrated event as their basis—Happy Birthday Annie (December 1, 1994) or 1st Name Piece for Clarinda, Happy New Year 1978 (December 31, 1977)—closely resemble Jackson's early works from the late 1940s and early 1950s. They are definitely and purposefully not illegible, due to the palimpsestic iterations of the original statement, which have been repeated and layered on the paper in pen, crayon, or acrylic. Finally, the exhibition closes with a series of thirteen drawings made in 1995; echoing the unsettled system of marks in Mac Low's early works, these drawings were composed by repeatedly handwriting terms that describe natural scenery, creating a ghostly impression with layered graphite marks. It is fascinating to me that in the last decade of his life Jackson's visual work circled back to his earlier prelinguistic explorations with drawing. It is obvious that he continued to feel this was territory that warranted further exploration.

* * *

Brett Littman is the Executive Director of The Drawing Center.

[1] Several of Jackson works were in Jay Sanders and Charles Bernstein's 2001 Poetry Plastique exhibition at Marianne Boesky Gallery. In 2012 Galerie 1900-2000 in Paris organized Jackson Mac Low Collages and Constructions 1958 – 1966. 2013 saw several of Jackson's Drawing-Asymmetries included in The Museum of Modern Art's There Will Never Be Silence: Scoring John Cage's 4'33". Most recently, in 2016, a series of typed poems on index cards (Gitanjali for Iris I – VI) were included in Carte Blanche to Karma: Olympia at Galerie Patrick Seguin in Paris.

[2] "Select a tree* Set up and focus a movie camera so that the tree fills most of the picture. Turn on the camera and leave it on without moving it for any number of hours. If the camera is about to run out of film, substitute a camera with fresh film. The two cameras may be altered in this way any number of times. Sound recording equipment may be turned on simultaneously with the movie cameras. Beginning at any point in the film, any length of it may be projected at a showing.

*for the word "tree,", one may substitute "mountain," "sea," "flower," "lake," etc.January 1961 The Bronx"

[3] "Each of the Drawing-Asymmetries may be performed alone, or with other Drawing-Asymmetries, by a single performer or any number of performers. Each performance begins by reading any word on the drawing in any manner suggested by the way the word is drawn. All possible parameters of reading each word (loudness or softness, pitch changes, etc.) are to be inferred from the word's appearance. Each performer should leave plenty of silence between the words, regulating the amount of silence by the amount of white space and the degree to which the words are crowded together or far apart." Jackson Mac Low, Doings, Assorted Performance Pieces 1955-2002, (New York: Granary Books, 2005), 54.

[4] Jackson Mac Low, Doings, Assorted Performance Pieces 1955-2002, (New York: Granary Books, 2005), 45