In Their Own Words

Emily O’Neill on “it’s too dangerous to tell the truth all at once”

it's too dangerous to tell the truth all at once

people begin with this poem is

& I want to interrupt them

to admit unvarnished

to lick sugar

from your fingertip / to attempt

knowing the rate of failure

how many parking tickets is it worth

to risk saying what you mean & being

heard? I tell the Dad story

where he meets Capote at a bar

& they both stare at some redhead / a cipher

for hunger with no outlet

because even though she dies at the end

she was loved enough / Pacino robbed a bank

over it & that movie cracked a year in half

you know Dad is dead by now & so is Capote

& the friend who bought their drinks & the bar too

but you're still listening / so it's not maudlin

worth mentioning if it pairs

with what else is on offer / me, touching your hand

when I make your change / parking meter running out

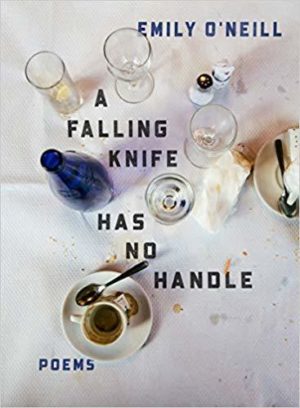

From a falling knife has no handle (YesYes Books, 2018). All rights reserved. Reprinted courtesy of the author.

On "it's too dangerous to tell the truth all at once"

I worked at the same coffee shop for a large portion of my twenties, in the Kendall Square neighborhood of Cambridge, a few minutes' walk from the MIT campus. I hesitate to call this the poorest period of my life, since there are many times I've been poorer than I realized, but I was absolutely struggling to make ends meet. I biked twelve miles a day regardless of weather to avoid the costs of public transit. I ate whatever was on sale at the Rite Aid around the corner from my apartment instead of buying real groceries. I taught adult education classes in downtown Boston not because I wanted to teach, but because the money was the only barrier between me and homelessness. There were months when I would sell the nicest things in my closet or on my bookshelf in order to pay my share of the bills. I loved nice things, but I couldn't afford to have them.

I started writing a falling knifes no handle at that coffee shop by falling in love with one of my regulars. He was a bartender who worked across the river near Boston Common. He lived around the block from my shop and came in almost every day for an espresso and a pour over. Most, if not all, of the poems in the book are letters to him. "it's too dangerous to tell the truth all at once" is a poem about the beginnings of our relationship. When I worked at the coffee shop, I spent all of my free time reading poems, writing poems, and attending poetry readings. He spent all of his free time at bars: either the traditional kind, or my coffee bar. He told me that he thought of the shop as his neighborhood bar; it was hard for him to go to a regular bar and not be distracted by what they stocked and how they made a drink compared with his own bar. Coffee was different because, though he knew what he liked about it, he had no idea how to make it as well as we did.

The title of the poem refers to how I often feel when first getting to know someone. Despite the excitement of connecting with strangers, there are many things about my life that are the wrong kind of exciting and scare people off. I couldn't talk about money or ambition or personal history with this man without feeling too exposed, or like I was imposing on him, my customer, who was maybe only being nice because he was grateful for the caffeine. The first line is an interruption of all the writerly language I was steeped in—this relationship interrupted my single-minded immersion in only maintaining relationships (friendships, romances) with other writers—an interruption that opened the door to talk about something other than writing for once. I don't much care for conversations of craft. How something comes to be is interesting, but intent isn't as important to me as effect.

The effect of getting to know this person was a relationship I'm still involved in. I told him so many stories at the coffee shop that he would often get parking tickets from staying at the counter too long. I didn't find this out until we'd been dating for more than a year.

One of the reasons we bonded, beyond the coffee, was that his mother was terminally ill, and my dad had died a few years earlier. I was still very deep in grief at the time, but telling stories about my dad helped ease that, so I told him a lot of dad stories, especially the ones about my dad in bars. The poem includes one of my favorite bar stories my dad ever told me, one that I still tell people even though I've never been able to fact check it.

In his late teens and early twenties, my dad was best friends with his high school guidance counselor. Max wasn't substantially older than him, only old enough to act as an older brother of sorts, and they did everything together. Max also happened to be gay. As far as I know, my father was not. The two of them traveled into Manhattan together from the New Jersey side of the Hudson River and went to bars. My dad wanted to spend time with his best friend, and Max wanted to spend his time in gay bars, so that's where they drank most of the time. On one of these nights, Max was socializing while my dad hung back, transfixed by the only woman in the room, a stunning redhead surrounded by friends. According to my dad, she was the most beautiful woman he had ever seen. The man sitting next to him noticed how my dad noticed the woman. My dad begged to know who the woman was. It was the summer of 1976, and the stranger asked, "Have you seen the movie Dog Day Afternoon?" My dad enthusiastically confirmed that he had. Everyone had. The stranger laughed and said, "That's the bitch they robbed the bank for." At this point, Max rejoined my dad at the bar and said hello to the stranger. "I see you've met Truman." And my dad said he hadn't, because they hadn't met really, only had their brief exchange. So Max made the introduction. "Truman, this is Sean O'Neill. Sean, this is my friend, Truman Capote."

It helps to think that, like my dad, I know what stories will keep people listening. I trust content more than the scaffolding around it, so I built this poem by layering the events as a kind of collage and held myself back from explaining what they meant to me. From grief, there's always growth. It's important to me to include grief in the story of this relationship, because without it, there would be no story.