In Their Own Words

Christian Schlegel's “Peter” and “St. Peter's Hymn”

St. Peter's Hymn

My God! my living God—I am ill-shod

for want of sense and means, though callous-footed I, for you,

will beat dead-low ten acres' land with but a switch and rood,

and ay, this too:

I'll scrip your lessons plain upon the dew.

My brother! brother shy—I'll curse the fiend

hard by in hideous mirth (O carefree sin) awaiting you.

Your word persevers, boldened by its mystery, and he is spleen

though seeming true.

And hurls he all to darkness save the simple few.

My lord! my lord at last—the chime will call

me to my knees, my grave, to paradisiac light, and you—.

My days are toys and trifles—I have fallen—I will fall

as triflers do.

King, if my inmost heart be mine, will you that heart perfect in

you

and me with love surpassing me imbue?

Peter

Thou readiest thyself in grace more grace to see,

may he be praised, and holy love betimes

will shew the fear thou cached. Thou grip'st that key

without a faith in doubt and with a rime

of dirt beneath thy thumbnail, red and beige, the right.

Some signs give way to signs unmarked nearer the light.

On "St. Peter's Hymn" and "Peter"

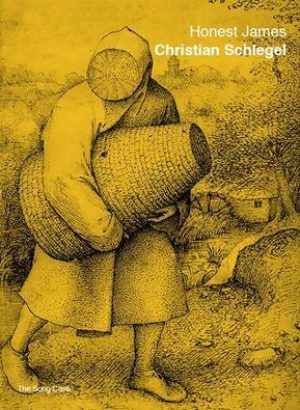

It's funny: now that I look at Honest James, and imagine myself back into the poems' different inceptions, I have trouble separating fact from fiction. Or: is it all fiction? Could I tell many plausible-sounding stories about the composition of each? I think so—and I was chatting about that, just today, with my friend Andy, on the phone. Both in Part I, a loose sequence of lyrics, and in the Goethe section (Part II), I've tried to join a remembered, or misremembered, ephemeral trail from something outside myself (an artwork or historical event) to something inside myself (a dream, an affect).

I studied German in college, and adored it . . . the deciphering of gigantic books . . . but more than that, I loved the existence of those books behind a haze of half-knowing, since my German was never great and is now quite withered and bizarre, I think. That half- or quarter-knowing helped me negotiate a deep anxiety during the MFA: that I've got no ideas, no good ideas, and certainly no new ones. I have discovered that this anxiety is, itself, an old idea.

I'm slowly figuring out that I do have the persistence of my misprisions. Chances are, I can be wrong, or some mixture of approximately allusive and autobiographical, in my poetry, in a "Chris Schlegel" way. So examples from German literature, and other non-English literatures, present an opportunity for individualized wrongness. (I must say, though: I remember a professor of mine, in college, distinguishing between novel and unoriginal incorrectness, implying that one can mess up exactly as others have. It remains a possibility.)

I'll talk, briefly, about two poems in the book, "Peter" and "St. Peter's Hymn," both of which take up my favorite character in the Gospels. My father and brother are named Peter, so, first, there's an immediate, significant association for me—I love them and my mother, Nancy, more than anything. But I wouldn't say either is "about" my father and/or my brother. Instead, the poems carry in them the framework of that devotion.

I could go on and on about my religious beliefs . . . I am, pretty profoundly, an utterly secular, progressive Lutheran . . . and I don't think it's coy to argue that those beliefs, however they're manifest, are apposite the poems. For me, Peter is the great character of the Gospels not because he's a perfect vessel for Christ's message, but because, as I've understood him—remembered and misremembered him—he's a perfectly human, fallible, complex, and therefore complete vessel. I hesitate to write more about Peter or the Bible, because of my propensity to turn passages to my own ends. As above: I read joyfully, and I'm a meddlesome reader.

"Peter" and "St. Peter's Hymn" are archaisms, attempted amalgams of poetries from hundreds of years ago . . . and I think they contain, and nurture, a love for people in my life, who are real to me and present. I can't vouch for the effects of the book, or of these two poems, but I hope their relation to my life is undone, or challenged, by their relation to other books. And I hope their predication on those books demonstrates that a person, Chris Schlegel, was involved in, or at least aware of, their production.