Old School

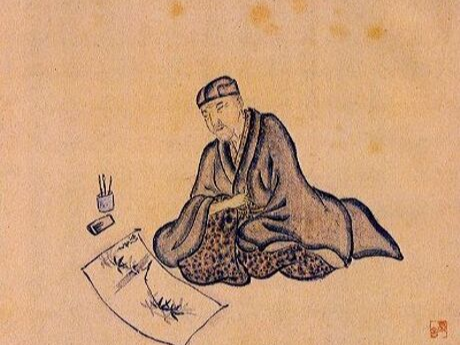

On Basho

REAL FLOWERS:

ON THE MAGICAL REACH OF BASHO

Sometimes the world feels weighty to us, like Atlas' burden, sometimes almost lark-light, unbearably sweet; Basho, the peripatetic 17th century Japanese poet, had a knack for distilling, in terse language, our seemingly contradictory sense of the world as onus and the world as gift.

Two decades ago, I selected lines from Basho as an epigraph to my second volume of poems, Soul Make a Path through Shouting: "Come, /see real flowers/of this painful world." Basho's haiku seemed an apt mirror to "Fleur," my book's penultimate poem, inspired by a passage from Ian MacMillan's Proud Monster, in which a Jewish boy, forced by Nazis to clean pavement stones with his tongue, finds "a tiny flower-shape" in a stone.

As my emotional and imagistic storehouse has expanded with the years, I've returned time and again to Basho's lines, to muse on their passing-through-this-world splendor. I love how the haiku's first word becomes an invitation to follow the poem's speaker, one that's quickly revealed as a chance to bear witness to the proximity of beauty and suffering that the roughhouse world presents to us everyday. There's a whiff of theatrical genius in Basho's gambit, as thrilling as Liza Minelli's kinetic Sally Bowles, beckoning to the audience with her rippling, emerald nails, to "come to the cabaret!" Will we or won't we join the speaker's journey into contradiction and suffering?

What exactly makes a flower real? The flowers in my treasured haiku have come to seem, over time, increasingly human—synonymous with my spiritual heroes, including the student-martyr, Sophie Scholl, and other dauntless young people caught up in the grim vise of World War II, whom I celebrated in my fifth book, The Crossed-Out Swastika.

I recently finished what I've come to refer to as a "fool's journey," in which I challenged myself to travel for weeks, carrying as little as possible, a trip that's made me prize, more than ever, the clear-eyed work and openhearted spirit of wandering Japanese poets like Basho. When I stepped off the train in Rome, once my home, I was greeted with an incredible, profuse aroma of jasmine, mighty enough to antidote my dismay at the massive, ubiquitous graffiti I'd encountered coming in from the city's outskirts—so much of it that I wondered if Rome had devolved into "an empire of spray paint": a reminder, an opportunity, perhaps, not to forget the possible literal flowers in Basho's eight homeopathic words; in the same breath, the world can suggest both a soothing garden and a brutally frank metropolis. It's part of the participatory glory inherent in traditional Japanese poems that Basho's cogent, sparking words can cross time and geography to seem so absolutely pertinent to the Holocaust and human heroism, or to a sweet-scented evening in Rome.