Old School

On George Oppen’s “Of Being Numerous”

"Obsessed, bewildered / By the shipwreck / Of the singular / We have chosen the meaning / Of being numerous."

I was 23 and self-effacing, my hair in a tight bun, when I read these lines, out of George Oppen's Of Being Numerous. I read them on my hour or so ride on the Q train, when I went to teach Brighton Beach community college students who had failed their basic reading and writing exam. That season, in which one of my students left obscene phrases on torn pieces of paper on my desk, I tried to teach poetry to him and the others and sometimes succeeded.

As for how I lived, I was, as Oppen wrote, one of the youngest people living in "the oldest buildings/ Scattered about the city / In the dark rooms / Of the past–and the immigrants, / The black / Rectangular buildings / Of the immigrants. / They are the children of the middle class."

The book Of Being Numerous was published in 1968, and yet there was so much about it that was still true in 1995. I was very young and like a character in Oppen's poem, I lived in a set of different nineteenth century walk-ups in the East Village. One had a hole in the floorboards; cigarette smoke emanated through it from the loud downstairs bar.

For the next two decades after reading "Of Being Numerous," I would hew to the poem's concerns and even personally, though unconsciously, emulate Oppen's path (more on that in a moment). I didn't know in 1995, that from the second I read the book it would influence my life.

Why is this poem so affecting? For starters, "Of Being Numerous," whose forty serial parts are all widely varied in length and subject, is a public poem about cities and ordinary people and their histories. It is more active than purely activist. It is an exemplar of "civic poetry," the movement I've been rabbiting on about lately. As civic poetry, "Of Being Numerous" is not precious or otherworldly but about the stuff of life: money, gender, corporate excess, and injustice. And today, civic poetry is on the rise with the work of poets and publishers like Claudia Rankine, Commune Editions, Anne Boyer, The Offing, et cetera. I try to write this sort of poetry myself.

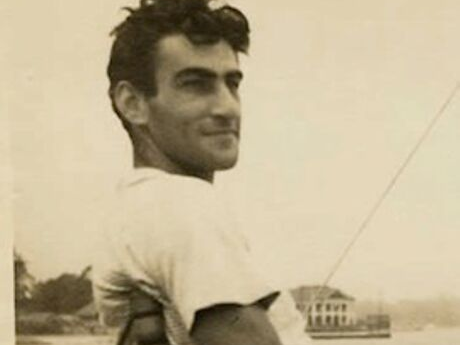

Then there was the effect of Oppen's biography. His life story produced, for me, a wave of narcissistic relief. He was the prodigy in reverse, the un-Keats. He was roughly 60 years old when Of Being Numerous was published. His brilliance came late, as a result, perhaps, of underproduction and delay. The poet famously gave himself over to his activist work—although in some accounts it was more like marriage and child-rearing, which I suppose could be considered just as radical at the time. He left poetry behind for roughly 25 years. He has said of his silence that he "didn't believe in political poetry or poetry as being politically efficacious."

I, too, gave up poetry, to enter the world of journalism. I felt the city and the country to be large enough to get lost in, as I believed Oppen did, so much so that that I wanted out of poetry, to go to interview people. I also gave it up because I felt rejected by the MFA sensibility of the time, so rusticated and pretty; I wanted to write on things that were decidedly not lovely.

Oppen switched off poetry too. This is central to his mythos: that he ostensibly ceased writing poetry entirely. "Clarity in the sense of silence," he writes in "Of Being Numerous."

When Oppen gave up poetry, he was a union organizer. He served in World War II—he was awarded the Purple Heart. He later worked as a carpenter and was a Communist Party member, ultimately moving to Mexico City, to escape a feared FBI investigation into his activities. The grad school narrative is that this work helped him forge his masterpiece, Of Being Numerous, that diving into the mosh pit of humanity without having to write about it ultimately improved his work. It was moving that he could pick it back up after having abandoned it. He avoided it, starved it, ignored it and it was still waiting for him when he returned—a bleakly romantic conceit.

I read the broad negative spaces that surrounded the spare lines of "Of Being Numerous" as an attempt to represent this choice of silence while writing poetry. It seemed to be synthesizing the opposition of quiet refusal and participatory noise.

Oppen's wide-angle vision captured New York City's ensemble cast of millions. His method was journalistic, political, musical, and empathetic. "Of Being Numerous" is very austere and gives off an ambience of phenomenology, like an Agnes Martin painting series. It would be easy for Oppen's poetry to seem valuable simply because its stripped-down, para-philosophical tone makes the reader feel clever without ever being bored or lost.

His previous elegant, cool, Marxian 1935 book Discrete Series was like everyday objects laid out on a pine table in a white room. "Of Being Numerous" was also cool but it was at the same time full of movement: self, humans, scurrying in a field of power and powerlessness at once. I saw it as a great end run around some of the clear pitfalls of minimalism in poetry. Minimalism's central fault is its potential decadence—becoming the poetry equivalent of the Calvin Klein flagship store. Oppen escapes this problem though his poetry's social sympathy, which is also that of the journalist, the social worker, or the field worker.

As he writes, "Phyllis—not neo-classic, / The girl's name is Phyllis / Coming home from her first job / On the bus in the bare civic interior." There is then an analogizing empathy—the New York City public becomes the blazing, horrifying public, linking Phyllis to atrocities in Vietnam and even JFK's assassination. "So small a picture, / A spot of light on the curb, it cannot demean us / It is the air of atrocity, An event as ordinary / As a President." These lines and breaks are still high fashion, with their boutique-y formalist enjambments. Yet the poem remains capacious in its topic and values.

I was a narrow and concentrated person when I first read Of Being Numerous, a grad student hoping to start a "career" in poetics, after all. But I felt I was expanding somehow, as I taught the poem to my students, even when confronted by the young man who preferred swinging on the classroom's Venetian blinds to verse. But I was an Oppen fan, the way other people that year were Pearl Jam or Dr. Dre fans, and as such I believed Oppen had curative properties.

When you're young you are not supposed to know who you are. Yet I knew who I was at 23 better than I do now. I would give up poetry, of course, and I knew when I started reading Of Being Numerous in 1995 that I would have to do that, in order to become someone else, in order to make a living. Twenty years later, I would find both poetry and Of Being Numerous still there, waiting, in all their expansive and cool difficulty.