New American Poets

New American Poets: Orlando White

Square Lips

1.

Open

the book's

mouth.

Flip through

each tongue:

ink breath.

2.

Read.

Eyes with four equal sides

are required.

3.

Stop.

A sentence:

a dark smile,

and its letters:

black teeth.

4.

Continue reading.

But don't

smile back.

Or else

the verb

and subject

will eat you.

All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

Introduction to the work of Orlando White

Kazim Ali

We have secret names and secret names for things sometimes. Neither is my first name actually "Kazim" nor my last name actually "Ali." Documents, legal instruments of a state which is man-made not intrinsic, do not tell the truth of our lives. Naming has more ancient roots, routes that lead us from truth to truth. Stein knew it, wanting to clean words of all their associations so they became viscerally real again. So does Orlando White, performing careful excavation on language and letters and the physical body as he does in Bone Light.

In the opening prose piece "To See Letters" White describes how language, the actual letters of the alphabet became physical to him through his first experiences learning how to spell, how to write with pencil on paper. As opposed to his mother, who allows young Orlando to circle random letters in her word search puzzles, the stepfather calls the young boy by his middle name and actually strikes him in frustration and anger when the child does not learn: "When David hit me in the head, I saw stars in the shape of the Alphabet." These letters, born from violence continue to have actual plastic and physical existence in the book of poems that follows.

Skull. Ink. Zero. Bone. Calcium. Skeleton. Paper. Period. Letter. Teeth. Bleach. Skin. Comma. Pen. Fingerprint. Rib. Noun. Socket. Milk.

Write. Dip. Press. Smear. Dissolve. Erase. Shake. Evaporate. Boil. Condense. Place. Suck. Pour. Fade.

Nouns and verbs and recur and weave themselves through this series of poems. It doesn't feel like a book length poem because the formal strategies and physical textures of the poems are so radically different from one another—formal couplets, fractured stanzas, open field composition—neither does it really feel like a "poetic sequence" because the emotional reach of the various poems, within their narrow and constrained vocabulary, is similarly diverse; some are stark and oracular, others funny, sly, wry. It is as if White is continuously evoking language as a living human object, like the text that flies free of books, soaking, caressing, or throttling the readers around it.

"Language, a complete structure/within the white coffin of paper. If you shake it/and listen, it will move, rattle like bones on the page," writes White. In this way, his language takes an active role, perhaps sinister, but the major feeling that emerges throughout the poems is that we must learn how language engages, transforms and controls us in order to then have the freedom to move in and out of it. "When you are naked,//you are unwritten," he says,

But, language likes to dress us up.

Position us

Next to one another,

so we exist as characters.

White's romance with language and the alphabet is not at all merely with recipient meaning, but also with its physical qualities, both inside the mouth and on the page. A particularly affecting series of love poems in the second half of the book traces the relationship on the page within the script of the alphabet of the lowercase letters "i" and "j." These same letters decorate the endpapers of the book.

By the end of the book, when White's initial encounter with language is retold, the striking fist of the parent figure is replaced by a pen similarly transmuted to a gun:

[…] But he finds me,

unwritten in the depths of the page. He lifts

the barrel of his pen, center on my forehead,

pulls the trigger. Through hair, skin, bone.

I feel the weight of ink enter my forehead.

the darkness takes up the white spaces

of my skull, I let him fill me with words.

Bone Light is smart, inventive, distressing, musical, disorienting, sublime. Orlando White is a poet deeply concerned with the living thriving hiving world and all the languages and sign-structures that create our understanding of it. If his intent and approach is that of phenomenology his execution is pure punk. Like Stein, like Dan Beachy-Quick, like Leslie Scalapino, when you read these poems what you are reading is a mind at active work and engagement with building blocks of reality. It's primally intense and yes, viscerally beautiful.

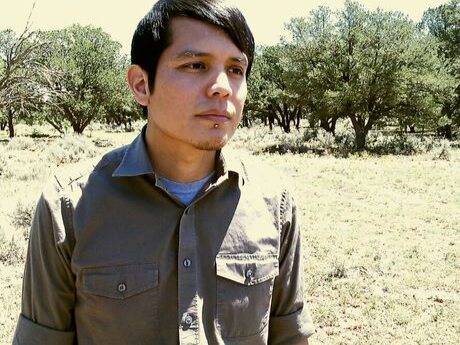

Statement

Orlando White

The poems in Bone Light received their energy from the idea of the caesura and composition by field. When I first heard of the caesura I thought, "A pause between language?" At the time I was also coming to understand syntax by omitting the period, comma, and semi-colon. Suddenly, through the use of the caesura I re-imagined punctuation as blank spaces. I conceptualized sets of words through the interposition of white space. I began to see that the rhythm and cadence of the line are determined by that space as well; the space invokes and animates silence. I recall reading "Maximus to Gloucester, Letter 27 [withheld]" by Charles Olson and being inspired by the poem's line breaks and the spacing of language. The poem begins in prose-like narrative:

I come back to the geography of it,

the land falling off to the left

where my father shot his scabby golf

and the rest of us played baseball

into the summer darkness until no flies

could be seen and we came home

to our various piazzas where the women

buzzed

After the first three stanzas, it unexpectedly shifts to abstract couplets:

This, is no bare incoming

of novel abstract form, this

is no welter or the form

of those events, this,

Then toward the end, its form suddenly discharges:

I have this sense,

that I am one

with my skin

Plus this—plus this:

that forever the geography

which leans in

on me I compell

backwards I compell Gloucester

to yield, to

change

Polis

is this

The poem on the page becomes a field of action. Its enjambments are organic and each one is accentual. Its punctuation feels ephemeral as phrases open up. Inspired by Robert Creeley, Olson wrote FORM IS NEVER MORE THAN AN EXTENSION OF CONTENT and I accede—in the moment a poem is written form occurs as a natural construct of the subject. And then, a poet becomes exempt from fixed structures to initiate a deep sense of imaginative form. POEMPATHY