New American Poets

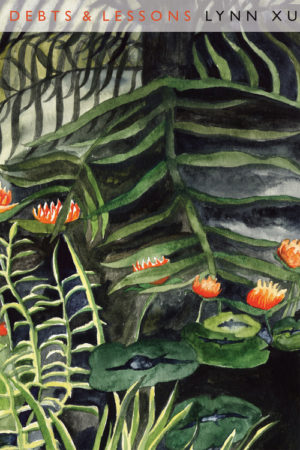

New American Poets: Lynn Xu

Lullaby

For Hart Crane

Are these pillars or are these waves

Slicing my cheeks like scuds of wheat

Eyelid by eyelid dividing me

O thou O hear

These thornless stalks of air

There is no time to lose

No keeping more obscene

No do not shout like that

Upon the sunlit limits of the night

Blindly pass

No work of words

Survey the senate of our minds

All rights reserved. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

Introduction to the work of Lynn Xu

Cathy Park Hong

When I read a collection, I listen for—to borrow Roland Barthes' term—a lyrical punctum which can be defined as a poem that uses prosody and word play to prick the surface of language and flood the reader with an irreducible spectrum of feelings that is as uncanny as it is instantaneous. This perhaps is a desired affect for any lyric poem and the most memorable and difficult poets such as Hopkins, Celan, Lorca, and Berryman (poets who Lynn Xu commemorates in her book) conjure this sonorous affect through a violent restructuring of language. Xu also strikes this tuning fork in her astonishing debut Debts & Lesson. While her poems are more restrained and subtler than the dramatic techniques employed by her poetic inspirations, Xu also crafts her lines so that they sing in a third language that always appears to stand on the threshold between languages, the threshold between the conscious and unconscious, and the threshold between the living and the dead.

Debts and Lesson begins with Say You will Die For Me that's impassioned lover's avowal but also a meditation on lyric's making: "All language is therefore a language of prayer. Held in the dark, without sleep." Here, I'm reminded of Susan Stewart's (Xu also mentions Stewart as an influence in an interview) observation that the poem "brings light into the inarticulate world that is the night of pre-consciousness and suffering." This first poem begins with the title's incantation and ends with "I am not asking for you to die for me. Say you will die for me." Such a pronouncement could be read as a romantic, whimsical demand for complete commitment but it's also Orphic in its utterance. Only through the lover's effacement, his banishment to the underworld, can his presence exist in the poem. The lyric must be predicated on the absence of the lover in the way the prayer is predicated on the absence of God.

Xu's poetry presents itself in center-justified margins; she uses radical enjambments and contorted syntax to create a music that's so incredibly compressed that even the hiccups of other languages feel seamlessly woven into her music (excepting the swaths of Chinese characters in "Night Falls.") Her verse carries a quiet global reach, especially in her series "Lullabies." Each poem is a dedication to an influence like the aforementioned poets. But they're not just homages or emulations but more collaborations in the tradition of Jack Spicer's experiments with Lorca. Here's a sampling:

For Osip Mandelstam

By shade of palm-slash

And by blood drying on the wind illusion

And I parted ways

I went to the dogs barking

Like women in the street

I touched them drank from them

They did not notice me

In "Lullabies," each poem is a palimpsest threaded with the dedicated poet's style, shaped by echoes of the poet's imagistic and prosodic gestures as well as a silence marked by shifting margins and use of white space. This excerpt could take place in Mandelstam's own transparent Petropolis and he could be his own shade. Each poem is a lullaby singing these poets to sleep, gently guiding them back to the underworld. The question is why the lullaby? Clearly theses lullabies are a young poet's apprenticeship and indebtedness to her predecessors. Is it a sly tease where the young poet is silencing the mentors to sleep so she can come into being? Or is she singing lullabies as an expression of repute and aid to writing? It is sleep, or the sensuous world of dreaming, that intravenously feeds a poet's inspiration. While Lynn Xu's lyric is consciously culled from poetic traditions, she has also developed a voice that is sui generis.

Statement

Lynn Xu

Several mirrors and revolving doors away, some blue planet shades into our sky. Intoxicated by this, as if by its own clairvoyance, the poem displays its plastic powers—fluoresces and, over time, decays. Still a transient and delicate substance, language nevertheless secures for us a strong interior, sharpness against our natural world. Of course, its occult successes in this regard must meet an equal measure of unsuccess: such that the leafy dark in the Courbet retain its phatic life, and the crisscross of rubble in Egypt not beautiful to the point of transparency or terror. Sometimes, a poem is made to furnish restlessness. Here, no longer romantic about its romanticism, the poem enters a satanic phase: dissatisfaction. Only fraudulence seems to make claims for truth, severe posturing, repetition, pain. The poem begins to take illusion seriously. It is not reflective, but lends passage to the unknown, generating visions, seizure, or deeper sleep. Technology develops to record the spectre of idea. Since we cannot face ourselves, self-denial acquires punishing power, pales in tempo, and draws sensation down. Not poorer for it, somehow, a fuller face appears. Do you hear it? The solitary body in the idleness of a painterly storm. This hallucination that something could be heard, beyond the vicissitudes of meaning. Today it is still not clear what the poem wants. Determination to give poetry the highest value . . . renders the poet absurd. And yet, for whatever reason, a certain density remains . . . a hesitation which refuses to toss this brightness to the wind.