New American Poets

New American Poets: Ashley Capps

What Constitues a Proper Planet

I decided to drive to the beach, where I sat in the sand and dug a large hole.

There was a tiny translucent crab with eyes like my mother

and such a specific inner life I tossed it fast back into the tide.

The sop I scooped out made a kind of wall which slid in on itself if my pace slackened.

I had to dig quicker. I dug frantic. Kids appeared with plastic buckets, little shovels—

I wanted to ask them not to collapse it, but they hung back, a cautious tribe.

Till at last, one poked me with a stick, and asked why I was doing that.

And I said, "To keep the ocean out." And then they all joined in.

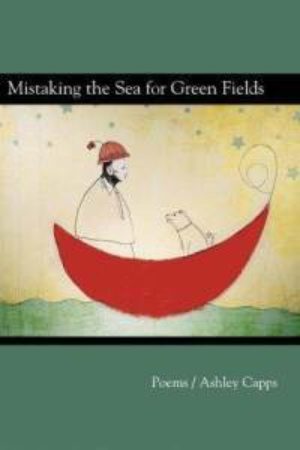

From Mistaking the Sea for Green Fields, with the permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Introduction to the work of Ashley Capps

Oni Buchanan

The poetry of Ashley Capps confronts the cruelty and ugliness of the world, and is urgently concerned with how to contain the information one has witnessed and simultaneously not lose oneself – one's identity or capacity to love – to its horror, how to avoid being pummeled into complacency and blankness by the knowledge: "I found out they'd been grinding chickens up behind my house. // Spent egg hens, / throwing them into the woodchipper live by the thousands, / cheaper than the slaughterhouse. // What do you think I did when I found that out. // You may touch me now, I am tame." This existential battle plays out in the lives of every inhabitant of Capps's poems, whose existences occur on the verge of suicide or in the deep clutches of self-destruction. The odds are against fulfillment – "A few out of ten thousand silver balloons / make it to the sea" – and the work pace needs to be breakneck just to maintain the remote possibility of escape ("The sop I scooped out...slid in on itself if my pace slackened").

The lives in Mistaking the Sea for Green Fields are choked with claustrophobia, lack of option, lack of direction, and the book is saturated with the distinct feeling of being buried alive. The speaker herself is awarded a prize for stillness, an honor for which all of her classmates were vying: "I myself in eighth grade won a contest for least visible movement. // The prize was to be a human mannequin for Sears." The predicament of too many lives cramped in a space of limited resource is encapsulated in her poem "Bottleneck," in which Capps writes: "All the trees / stuck under the old train bridge / since last May's flood won't budge. / That shit aint going nowhere / without dynamite, he says, and spits." Any evidence of transit – a way out – seems to go through or above the locale without stopping. The train tracks serve only as the location where, on countless occasions, generation after generation, "someone's sister los[es] it early." A huge orange hot air balloon leaves the speaker behind: "It came so low a minute ago, / I thought it would land. / I thought, Finally. / Then it filled like a giant lung and flew away." Meanwhile, the individual people of the landscape are deserted to their "gravity-strapped," domesticated lives. In their driveways, they "feel [their] heart[s] deflate a little, turn / back to the groceries softening in their paper bags."

While their peers and family members succumb to the atrocities that surround them, the survivors have to figure out a way to continue, without becoming "too attuned / to this darkness, too absorbent / of it." The speaker courageously searches for proof of a self and the self's capacity of something larger, setting out with her telescope to find "Proof I was more / than the seasonal ragbag detritus / choking the rooftop gutters." Poetry is the avenue of escape for this speaker, the literally life-saving highway out of town: "with you, I back-float / the massy and heretofore unnavigable childhood / algal blooms, where no fish swam."

In the face of the relentless superficiality, gaudiness, tawdriness, and self-compromise of this world, and despite the betrayals and barbarities committed by its inhabitants, against themselves and one another, Capps's poetry is filled with a deep and nearly desperate love for the people and animals that appear in her work. Much time is spent trying to save the other living beings along with the self, to ensure the conditions needed for metamorphosis. Of course, mistakes are made along the way: the cocoon which the speaker nursed for weeks turned out to be "a used cottonball / The shadow breathing inside was a stain / that belonged to someone." But the urgency of the work to nurture, to transcend, never slackens, and the book ends with the speaker's own industriousness inspiring a group of listless kids at the beach to join her in the endeavor, all of them kneeling down and pitching in with their plastic, dime-store shovels.

Statement

Ashley Capps

Paul Klee used to require his students to draw the same small objects over and over: reflections in a water glass; a small ball of wool; the seemingly endless facets on a suit of armor; a piece of birch bark; a leaf with a network of veins like fine lace. He required that the objects be rendered so precisely they might be "lifted off the page." Klee was no realist painter—most of his work could not even be called descriptive—but meticulous observation, and a state of vigilant attention and receptivity were essential, he believed, to developing the artist's power of perceptive judgment. Perception, for Klee, was revelation, "an insight into the workshop of creation." "Art," he insisted, "does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible."

*

In his essay, "Art As Device," Viktor Shklovsky, like Klee, sees the process of perception as a creative end in itself, and the goal of art not only to facilitate perception, but to rehabilitate it:

"If we begin to unpack the general laws of perception, we will see that as they become habitual, actions become automatic. Thus do all our practical skills retreat into the realm of the unconscious-automatic; whoever remembers the sensation he had holding a pen in his hand or speaking in an alien tongue for the first time, and compares that sensation with the one he experiences while doing it for the ten thousandth time, will agree…So, unheeded, does life fade away. Automatization swallows up things, dress, furniture, one's wife, and the fear of war. And if the whole life of people passes unconsciously, it is as if that life had never been."

Automatization, that deadening of perception that Shklovsky attributes to habituation, is a major effect as well of the alienating modes of modern life and advanced capitalism: mechanization, overstimulation, hyperconsumption, noisification, distraction-addiction…Shklovsky differentiates perception and automatization by distinguishing between seeing and merely recognizing— noting how much of our physical experience occurs at the level of unconscious recognition, rather than at the level of awakened sensation, so that we drift through coffee and traffic and see without seeing, hear without hearing, touch without feeling.

But art, Shklovsky counters, "art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects 'unfamiliar,' to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged."

Shklovsky goes on to discuss this technique of making objects unfamiliar, what he calls "defamiliarization," as the province of poetry and a way of combating automatization. I am encouraged by this idea because I often struggle to feel that writing poetry is a worthwhile endeavor. But if, as Shklovsky posits, recovery of the sensation of life is an aesthetic end, and what art exists for, surely this recovery is also an ethical act in a society whose dominant values rob the spirit, delude the mind, diminish awareness, and deplete the will to change. To see things as they really are—and to show them as they actually exist— is to trouble reductive definitions and pernicious, empty categories that enable harm. "To make the stone stony" is also to make the pig porcine, for example. If I can write a compelling poem that defamiliarizes pigs, reorganizing them into their proper category of highly intelligent, emotionally aware, sentient creatures who desire to live, and to be free of fear and pain, rather than abstracting them into the devitalizing categories of "meat" or "livestock"—then the moral incoherence of eating pigs but protecting dogs becomes more visible, and the disgrace of breeding animals for enslavement and slaughter, when we have food choices that do not depend upon enslavement or slaughter, becomes, perhaps, more clear.

That's just one example of something I think a defamiliarizing poem could do, and of what to me would be a worthwhile poem to write. More generally, wherever I am in my writing right now (and that's always largely a mystery to me), I am focusing on the possibility of poetry to renew perception in myself and in readers; to revivify language; to promote attention and mindfulness; to restore wonder; and to recuperate empathy and a sense of connectedness by scouring from things and experiences the hardened film of familiarity by which they are diminished, and beneath which they are lost to us.

*

"And I always thought: the very simplest words

Must be enough. When I say what things are like

Everyone's heart must be torn to shreds.

That you'll go down if you don't stand up for yourself--

Surely you see that."

—Bertolt Brecht