Interviews

Interview with Jill Bialosky

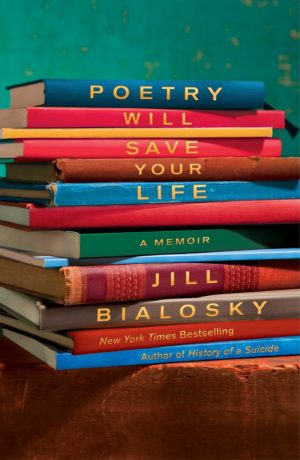

Jill Bialosky is the author of four books of poetry, most recently The Players, as well as three critically acclaimed novels and the New York Times bestselling memoir, History of a Suicide: My Sister's Unfinished Life. She has lived for many years in Manhattan, where she is Executive Editor and Vice President of W. W. Norton.

In creating Poetry Will Save Your Life, Bialosky has applied these many facets of her own life. The book gathers fifty-one of her favorite poems in an anthology of both classic and contemporary work. For Bialosky each poem is a stepping off point for her engaged commentary, ranging from the analytic to the intimate. She shows that a poem is more than homework, more than an object to be scrutinized. A poem can be a deeply personal document that also possesses an important social purpose and wide relevance. Poetry Will Save Your Life is unique in recent publishing—a genuine hybrid, part literary discussion, part memoir, written for a general audience.

* * *

DB: It's a treat, Jill. to talk about your new book Poetry Will Save Your Life: A Memoir. Can poetry really save lives? I think about William Carlos Williams' statement that, while a poem may not give us the day's news, people die "miserably every day for lack of what is found there."

So what is found there in poetry? What is found there that saves lives?

JB: Many readers have asked me this question based on the title of the book. Can poetry literally save lives? It depends on what aspect of a life we're talking about. And obviously, there's is a bit of tongue and cheek and playfulness in the title. I'm referring to our inner lives and the way in which consciousness and identity is fortified. If one is dying from a chronic condition, poetry could not save that person (though there have been scientific studies on the healing benefits of poetry and many hospitals include poems on their walls and bulletin boards), but perhaps a poem may allow for shared solace or acknowledgment of mortality. I think of a poem as its maker whispering in the ear of the reader. Read this poem. See if it makes sense to you. See if it touches on your experience. Revel in the mind of the poet and the way language and imagination can shape experience and create its own reality. Literature and poetry impact consciousness and the way in which we continue to probe, invent and stretch intelligence and imagination. Critics would balk if I considered poetry a form of mindful gymnastics. But why not. It's elastic. It stretches our thought process. It invites nuance and encourages non-literal thinking. A good poem awakens. Allows us to think or feel something we may have not known how to articulate unless we read it in a poem. It also allows us to dwell or marvel at what we've taken for granted or forgotten, the smallest details, to renew our sense of awe and wonder, to see the world strangely, to look again at the magic of the natural world, for instance. It's interesting to consider the ways in which sturdiness and stability in character is formed. If we consider the self as continually in flux than yes, poetry builds resilience. Political poetry, poetry of social concern and conscience, politically engaged poetry has the power to be a voice of resistance, engagement, and revolution. I've heard political poetry described as a poem that is self consciously written inside history, so to speak. So yes, I do think poetry can have a tremendous impact on personhood, culture and society.

DB: What was the biggest surprise for you as you gathered poems and wrote your commentary for Poetry Will Save Your Life?

JB: I recognized how poetry has informed my thinking and emerging selfhood, my abilities to be open to the many different levels of reality we inhabit. If you are a thinky person like I am, and the mind is constantly alive and making connections, poetry is a steady balm. Poems can be companions when we're suffering, grieving, longing for something that isn't quite possible. Even a line of poetry, here I am thinking of Hopkins' "the mind has cliffs of fall," is filled with endless possibly for thought and consideration. If I had another life to lead—meaning more time—I might consider shaping a course or curriculum where poetry would be a thread throughout the educational process. A poem can allow the mind to be aware of many possibilities that exist all at once, in Keatsian terms, to live without an endpoint, in uncertainty, without answer. On another level, I realized collecting and thinking about the poems in Poetry Will Save Your Life how the individual voice of a poet shapes the poem and that the poem cannot be separate from the poet writing it and yet anyone can enter it. Poetry is basically a humane art. An art that is without prejudice or exclusion. We forget that.

DB: You spoke earlier of the whisper of poetry—the maker whispering in our ear. It's a voice I want to hear when I read about poetry, too, the voice of a guide and good companion. I hear it throughout Poetry Will Save Your Life.

You say you fell in love with poetry in fourth grade. Was it the teacher, Miss Hudson, or was it the poem, Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken"?

JB: I wonder if it was a combination of both. Miss Hudson was one of those few teachers that left an impression. A friend I grew up with read the opening portion of my book and wrote to me that she too remembers Miss Hudson reading our class "The Road Not Taken." Over time that experience, hearing the poem read, and finding my own way in it, was a poem I kept returning to, thinking about, when as a young person we begin to think of who we are in the world and over time my thinking of the poem changed as my own thinking matured. I could have written about Elizabeth Bishop's "In the Waiting Room," a poem that may have touched me in some way at that particular time, but I hadn't come across it then. What I admire about the Frost poem is how one can read it in many ways. It's not a poem that closes down. It keeps opening and unwinding like those roads. And at a crossroad in our own lives we remember it. Perhaps that's why it has become iconic. And why I chose to write about it and my experience with it in the opening section.

DB: I understand that. The Frost poem rewards rereading. Its mysteries deepen even as its story clarifies. Frost's poem is so clear that children love it, and it's so bottomless we continue to love it into adulthood.

Kids do love poetry, don't they?—the music, the rhymes, the incantation of rhythm. So what happens when they turn away from it? Am I right to think this turning away often happens in junior high or high school? Are we teaching poetry wrong?

JB: I'm not sure. If I were a teacher of poetry I would choose poems to teach that I hoped would have an impact on the classroom and on the students' lives. When I wrote into the concept for Poetry Will Save Your Life, I remembered the poems, nursey rhymes, jingles, prayers and psalms that marked my childhood; for instance, "Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star," or "The Swing," and "My Shadow" by Stevenson. And the famous bedtime prayer, "Now I lay Me Down to Sleep." Then I didn't think of them as Poetry with a capital P. But when I began to put this book together it occurred to me that poetry had followed me long before I knew about it and I wanted to make that connection in the memoir. I remember my son one day came home from elementary school and shared with me Mark Strand's poem "Pot Roast" about the speaker eating pot roast and remembering his mother's pot roast and those last lines: "The meat of memory./ The meat of no change./I raise my fork in praise, /and I eat." Did he understand the nuances and complexities of that poem? I'm not sure, but I think it delighted him to find a commonality in a poem. A poem can be about Pot Roast! The language of the poem changes as we change throughout history. On the other hand, my son also came home from ninth grade with the assignment to memorize lines from Chaucer's "Canterbury Tales" in Middle English. Did he understand completely what he was memorizing? I'm not sure. But I do think he enjoyed the rhythmic sound and challenge of the language and its historical significance in English. I wrote Poetry Will Save Your Life with a reader in mind who may not have connected with poetry and the hope of drawing that reader in. It's not meant to be a handbook to the art or to encompass all the art can do and say. And because I am not an academic, it was not written to be an academic book though some poets who have read it have told me that they'd like to teach from it.

DB: I think your last point is what strikes me most. There are professional academics who may find your discussions too plain or just too personal. Those old New Critics wanted to hyper-analyze a poem as though it were a lifeless artifact; and the poststructuralists often foreclose any public discussion of literature by their own jargon and critical techniques. These things tend to shut down the prospects of pleasure and usefulness.

Here's what I mean. No academic scholar would dare say about a James Wright poem that it "shimmies down the page"! But that's a great description of Wright's dynamic sense of line in "A Blessing." In the short paragraph you write about his poem, you clarify Wright's pastoral story about horses in a field even as you engage with the narrator's internal feelings. You make the deep connection between the nature poem and the love poem. And you arrive at your discussion of Wright's poem through a personal story of the summer before you went to college, "hang[ing] out in the barn."

JB: I love that James Wright poem. It makes me smile when I remember it. And often when I'm driving in the country and see horses nuzzling one another that last line comes to me: "Suddenly I realize that if I stepped out of my body/I would break into blossom." That's a line that only poetry could discover. It's the idea of "love" as a "breaking into blossom" that gets to me. See any young lovers together and you can feel it happening. I agree that professional academics and New Critics and poststructuralists would be all over this book. Maybe in a way, it is a subversive act on my part, to pair poems with aspects of my own life and to show my own engagement with the form. I've never seen anything like this sort of hybrid and that pleases me. My purpose is not to show how poems are made, but rather their affect and the way in which they touch upon aspects of human engagement. Perhaps newer generations of poets don't think this way. I'm willing to be old-fashioned in defense of an art I care about. Perhaps young poets are schooled to consider poetry as language separate from experience, if you will, the same way in which Bly, Wright, and Kinnell, for instance, put forward the "deep image poem" as a response to Pound and Eliot. We are witnessing a moment of change in poetry. Poets are using the poem and language to claim identity and reshape it. It's an exciting moment.

DB: What enchants me is how easily you move from analysis to personal narrative. Sometimes in a single sentence. Your book is full of poems—fifty-one of them, reaching back to Shakespeare and forward to Li-Young Lee. But this book is also full of Jill Bialosky. Your subtitle, "A Memoir," speaks to this aspect of the book.

Reading a poem for you is a deeply personal thing. I am moved by your bravery in using your own life—how you came to poetry after your father's death, the deep sorrow of your sister's early death, your mother's recent struggles.

That's what I carry forward from Poetry Will Save Your Life. A poem isn't homework. It's a life story—the reader's life.

JB: Yes, as a poet that's what is unique to me about poetry. How close it is at capturing moments and experiences that remain unsaid, that can only be accessed through a poem. A poem is personal in the sense that it is shaped from a poet's psyche. Think about it in Frost's terms. "How way leads on to way." We don't know what will happen next until we put a thought down, and see where that leads, whether it is a fragment, an image, a line of meter. It was freeing to use the self as a throughway and to claim one's own experience, knowing of course that it is always in flux, or shaped by a moment of recollection. I admit that as I wrote further into the memoir I recognized that some readers may not connect to the personal anecdotes but at the same time I also recognized it was the only way I wanted to write about poetry, at least now. And therefore, I claim it as "memoir." I write in my preface that the definition of memoir is a historical account or biography written from personal knowledge or special sources." Poetry Will Save Your Life is a combination. Poems were my sources, so to speak that allowed me to create mythologies of my own personal experiences. I almost said in the preface, or perhaps I did in an earlier version, that the reader might create their own personal map through poems. Writing is essentially a courageous act and I'm interested in creating new ways of connecting poetry to readers. I also enjoy reading poetry criticism, deconstructing poems and thinking about the form's progression over time and its influence and responsibility on a constituency. It's endlessly interesting to me. As an editor, I get myself out of the way when I read a manuscript or a new book of poetry and find the poet's intention. My tastes in poetry are broad, despite the close experiential lens Poetry Will Save Your Life projects. My intention is to open the door to poetry for new readers. Academics and critics, be damned.

DB: Ha! But now I see how your title works. The "salvation" in the title means a number of things. We can rescue ourselves in poetry. We can find those redeeming or life-giving elements. But we can "save" our lives, too, through the memory that poetry helps construct.

JB: Reality and life don't always coalesce, but in a poem that can happen. Writing poems is like writing in a new language, once you discover it. And in essence, it is the same for reading a poem. And once that language becomes a part of you there are many ways in and out of poems. Like novels, some poems are social, political, ecological, deeply personal, and communal, some are written out of love, rage, sadness, joy, some delight in word play entirely. Some are edgier, more puzzling, but you know when a poem is meant for you or speaks to you or an aspect that invites a memory, an emotion, a sense of outrage, awe and communality. I continue to learn from poems. They stretch my thinking and my humanity and empathy. I like how you put it, that we can rescue ourselves in poetry.

DB: So when did you begin to think about writing this book? Which poems came first? And how did you conceive of the structure and the approach here? Who do you imagine as your reader?

JB: The book unfolded in an organic way. It originally was to be a short anthology of the poems that were essential, poems that enrich, a short book of poems that were accessible and touched on life experience and would allow readers who don't normally take their coffee with poetry a chance to think of a poem in a different way. And then I recognized that if I were to choose poems to put in a book I needed to say why these poems, and so I thought that I would create a blueprint of sorts of poems that were crucial in my own coming of age. And once I began this journey I couldn't stop. I found it more interesting, especially since the choice of poems for me were primarily experiential poems. To get back to your question, I was not thinking of a poetry audience for this book, but more for the general reader and young adult interested in becoming acquainted with poetry through a different lens. In this case, the lens is my own mythmaking of aspects of my life and how they relate to certain poems. I've read many books about poetry, some that are books geared toward prosody, others toward teaching poetry, but I haven't seen a book like mine, a sort of hybrid of poetry and memoir, that engages with poetry on an intimate personal level.

DB: I bet you had lists and lists of poems to include. The poems here share some characteristics. They tend to be short—from Gwendolyn Brooks' ten-line "We Real Cool" to Adrienne Rich's "Diving into the Wreck" at ninety-four lines. They tend to be story-driven. They tend to be clearer than obtuse or scholarly.

Are these your favorites? Did you leave out any favorites?

JB: As I began this enterprise, there were many poems I wanted to include and many different poetic voices I wanted to share. I stayed on course with what I set out to do, to choose poems that were somehow fundamental to me at a crucial moment in my own life. Or poems I discovered later that brought that experience alive again for me. I decided to not include any poets that had a birthdate after my own. The book was not meant to be inclusive. As I began the project I recognized that I could write a mammoth book if I wanted to choose many more poems, but the idea was to engage with an audience newer to poetry and hence I wanted a short book. I would however, invite every reader to make their own blueprint through poems. I recognize that this idea may bewilder poetry critics or poetry theorists but that isn't my audience. What are the poems you put on your bulletin board or refrigerator? What poems are the ones that make you nod? Or remember?

DB: Adrienne Rich's poem, "Diving into the Wreck," speaks to a particularly important subject for you, doesn't it? Your representation of women poets is timely and important. You even introduced me to a couple of women poets I didn't know! The sisters, Jane and Ann Taylor. Is it notable that we all know their very famous poem that begins "Twinkle, twinkle, little star," but not their names?

Can you say more about the role of women here—in your life but also in the art?

JB: You know, I'm not sure that gender is finally at the heart of it. Adrienne Rich and the poem I chose to include of hers, "Diving into the Wreck" is a landmark poem. It created a pathway for women to authenticate their own experiences into poems and as Eavan Boland would say, to claim their experiences as an act of inclusion; to write their experiences into poetry. Her first selected we published at Norton is called Outside History. There are other poems and poets who were influential, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, Muriel Rukeyser, for instance. In my selection, I stayed true to my intention. It just so happens that poems by Sylvia Plath, Emily Dickinson, Louise Bogan, Eavan Boland, Louise Gluck, were companions throughout my coming of age and I can trace the ways in which my own thinking responded to those poems. I can't tell you how many times I read Louise Bogan's volume, The Blue Estuaries and how lucky I was to come across Louise Gluck's The House on Marshland, which was the first book of hers I read, and then later each of her books became deeply personal to me. I enjoy returning to my own poetry library and remembering all the volumes that were crucial to me as a young poet. I'm sure you share the same experience. I loved finding out that Jane and Ann Taylor wrote the poem that would become legendary for all children! What young American does not know "Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star." It's a simple poem but also quite complex. That's a monumental find.

DB: I feel that way about your whole book, Jill. It's a wonderful find. So, thank you taking time to talk about Poetry Will Save Your Life.

As it goes out into the world now, into the hands of readers, what is your biggest hope? What do you aspire for this book?

JB: We all lead public lives but within those public lives we finally live inside ourselves. Everyone is fighting a battle we know nothing about. I'd like for a reader to read one of the poems in the book and say, oh yeah, that reminds me of this experience, let me think about that moment again. Why do I feel sad today, or lonely? Or ecstatic? Let me reread the poem. Let me be quiet and let the words settle in. Let me be seduced by the music and rhythm of the poem. What does that last line mean, "my body would break into blossom" [Wright] or "I'm Nobody, Who are You?" [Dickinson]—let me find companionship and humor there, too. Or open the book to the section "Terror" and read the poem "Try and Praise the Mutilated World," [Zagajewski] and remember when terrorism was in our midst and remind ourselves that we are not inured to forces of evil. Or come across that wonderful line in Plath's "Nick and the Candlestick," "oh love, how did you get here," and connect to that beautiful miracle of a new born child. Wouldn't that be lovely.