Poetry & Environmental Justice

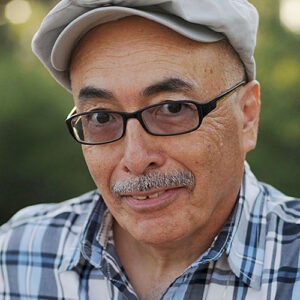

Anaïs Duplan on “Let us gather in a flourishing way” by Juan Felipe Herrera

Let us gather in a flourishing way

Let us gather in a flourishing way

with sunluz grains abriendo los cantos

que cargamos cada día

en el young pasto nuestro cuerpo

para regalar y dar feliz perlas pearls

of corn flowing árboles de vida en las cuatro esquinas

let us gather in a flourishing way

contentos llenos de fuerza to vida

giving nacimientos to fragrant ríos

dulces frescos verdes turquoise strong

carne de nuestros hijos rainbows

let us gather in a flourishing way

en la luz y en la carne of our heart to toil

tranquilos in fields of blossoms

juntos to stretch los brazos

tranquilos with the rain en la mañana

temprana estrella on our forehead

cielo de calor and wisdom to meet us

where we toil siempre

in the garden of our struggle and joy

let us offer our hearts a saludar our águila rising

freedom

a celebrar woven brazos branches ramas

piedras nopales plumas piercing bursting

figs and aguacates

ripe mariposa fields and mares claros

of our face

to breathe todos en el camino blessing

seeds to give to grow maiztlán

en las manos de nuestro amor

“[Let Us Gather in a Flourishing Way]” from Half of the World in Light: New and Selected Poems by Juan Felipe Herrera. Copyright © 2008 Juan Felipe Herrera. Reprinted by permission of the University of Arizona Press.

On The Importance of Psychomagic, Gathering, and Poetry

In [Let us gather in a flourishing way], Juan Felipe Herrera imagines both “struggle and joy” as a sort of garden. He invites us to see that struggle and joy come from the same source, this garden, where he then invites us to gather. Or even, to flourish.

The lack of punctuation in the poem causes each individual word to start to act as an object in this myriad collection of things. The poem quickly becomes a dense gathering of objects, people, food, and nurturing. So too, the refrain, “Let us gather in a flourishing way” challenges me to imagine what flourishing looks like. I’m invited to add my own vision to the many images that Herrera strikes up vibrantly, as he does, for example, in the line “carne de nuestros hijos rainbows.”

That the poem is written in Spanish and English speaks to a kind of abundance that goes beyond a single language. I love the line breaks in this poem, how Herrera keeps his lines close and short, to emphasize the bilingual music he builds. Because of its music, this is the kind of poem that wants to be orated. It wants to be heard again and again.

In hearing the poem recently, again and again, I was reminded of a guided meditation where the teacher noted that, because there are almost eight billion people in the world, no internal experience truly belongs just to one person. Every feeling state is shared across those billions of individuals. With that in mind, the ideas of abundance and gathering, given the last year we’ve just had, aren’t so far-fetched.

Reading this poem, I find myself asking, how do we sustain abundance across time? These times specifically? How can one exist in a place of nurturance given a global pandemic and the detriment it’s caused to our communities’ physical and mental health? How do you find a place of abundance when there’s so much cause for strife, given racial inequality and the deterioration of our planet?

Herrera’s choice of the word “flourishing” speaks directly to this illusive idea of sustainability, both personal and environmental. The flora, fauna, and food of this poem stand for the ability to imagine oneself loved and resplendent. I relish the call to gather “contentos,” the call to gather bodies, flesh, family, and even rainbows—a very gay image, I might add. These are all images that bring joy and it takes courage to write a poem like this. It’s much easier to be critical, to see our world in a negative light.

I imagine being a creative leader who sees the positive and yet, at the same time, doesn’t fall prey to “silver linings.” Positive leadership is not a negation of what is bad about where we are; it’s not about not seeing the negative, but rather about focusing and harnessing the power of a movement around the act of celebration. Movements that aren’t built on joy don’t last. We should aim to hold the “struggle and joy” jointly, to highlight celebration alongside pain. Justice movements aren’t just about social or environmental outcomes, but about trying to instill a new, more nuanced way of being with (and seeing) what is.

In movement-building, there’s a deep desire to feel understood. To this, there are two possible responses: first, the negatively-oriented work of striving to feel understood by those who don’t already understand and second, the work of empowering those who already do understand. This poem takes the latter route. For instance, [Let us gather in a flourishing way] welcomes Spanish-speakers to feel seen and understood. The problem of translation (i.e. how to bring one complex set of meanings into another language) disappears here. Rather than engage in translation, Herrera enjoys speaking to those who already understand, share a cultural background. The poem gathers joy in that shared place. In shared joy, there’s shared power.

¹ Recently my girlfriend lent me Alejandro Jodorowsky’s book, Psychomagic: The Transformative Power of Shamanic Psychotherapy. Before reading it, I was admittedly skeptical about more esoteric practices but I was quickly sold on the importance of engaging the psychology in a sort of magic meaning-making to bring about individual and group healing. I highly recommend the book.