In Their Own Words

Monica McClure on “Making Up”

Making Up

I had to approach her as an idea

Not yet contoured

Where she might have shrunk I picked up

Eyebrow pencils

And made her submit

Her face under my forearm

So what if my mother was more shadow

Than shade

What I see in her face, I wonder,

Does it show?

The under-eye crash diet of the soul

A mouth hiding from a voice

What if my tools dispense light

I cocked my chin to move closer

And I noticed she held her breath

The more petrified the mother

The more she fears her daughter

I would rather create something new

Out of us

But I am also being mineralized

Rapidly over ages

I have a threadbare vocabulary

A stagnant nature

Like a pond that has seen better days

So heavy in my blood

Murky and parasitic

I am making up my mother’s face

In my own image,

An act not unlike forgiveness —

pruning, weeding, fondling,

Gloves on, mending wire fences

Someday I’ll have a daughter

But for now, I work with what I have

Her face is diffident

Unforthcoming in a way

I’m too chicken shit to prod

My mother is a receding gale

Thunder in her own weather

The more studied a forecast

The more potent its threat

Off stage ballerinas look like cattle

After a roundup, tired, pulsing

I ran away from my mother

To wear exquisite perfume

And cradle a small dog

I’ve lived like a poet

And worked like a man

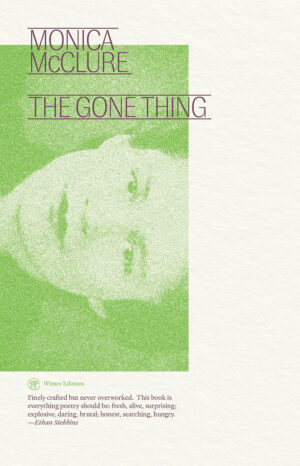

Reprinted from The Gone Thing (Winter Editions, 2023) with permission of the poet. All rights reserved.

On “Making Up”

These days, I think most people learn makeup from strangers online—tutorials abound on YouTube and TikTok for every trend, subculture, and aesthetic. When I was a tween, the options were more limited. I committed to memory the techniques I read about in fashion magazines set out in waiting rooms or on grocery store checkout line racks. (These magazines weren’t permitted to come home with me.) For hands-on learning, my generation relied on people we knew—often our mothers. We presented our faces to be manipulated and enhanced, trusting that they knew best. We let our hands go limp in our laps and hoped for good results. We had to believe that they saw at least an approximate version of what we saw when we looked in the mirror and knew what to do about it. Because back then, the role of makeup in our culture was narrower: to make women more attractive. But that’s another story.

Have you ever done your mother’s makeup? It’s thrilling and tender. Her breathing becomes self-conscious. You’re reintroduced to her unique scent cocktail: her sour-sweet breath, her white floral perfume, the mineraly oil of her scalp. It’s both a role reversal and a presentiment. You come face to face with a probable future in which you care for her body in more essential ways. And your faces are so close.

There’s an obvious power imbalance to this makeup-doing: a teacher-student relationship enacted through physical touch. Grooming is wonderfully erotic yet chaste — one of those encounters where the wholesomeness electrifies it. There’s a template to follow. You’re either the one submitting or the one in charge; with the ultimate goal of making the submissive feel more beautiful. While she’s in control, the makeup artist is accountable and in service to her subject.

I did my mother’s makeup in the same house in front of the same bathroom mirror where I remember receiving early lessons in the art of femininity, and a year later I wrote a poem about it. By then, I was pregnant with a girl and in some ways this made me a young girl again. I felt like I needed to spend time with that girl before leaving her behind to become a mother to my own young girl child. In hindsight, I know it to be wrongheaded. But I had no idea what I was getting into. No idea how many iterations of my girlhood would reemerge in the years to come.

Now there is the relationship with my mother, which has generally been fraught, and the resolution I suspected had occurred in this exchange where I was in charge and she was submitting, thus the double entendre “Making Up." Mothers loom so large. It’s good to be reminded whenever possible that they were once girls, teens, and young pregnant women who themselves had much to learn. Playing the mother role to my mother in this moment smoothed a wrinkle between us. But now that I was to be a mother, writing poems inside a transforming body, new pores were opening up and being filled with old angry grievances. They were the complaints of a hurt child, unadorned and exposed.

I think deep down we expect impossible things from our mothers. We want their whole world because once their bodies were literally our entire world. As a child I was frustrated by anything unknowable about my mother, as if she owed me full access to her interior life. And like a rejected lover I sensed she wasn’t equally curious about me and I resented that. Though maybe she was and I was just as impenetrable to her, or maybe I failed to recognize her interest, immersed as I was in the innocent narcissism of childhood.

Still, it’s unfathomable to think that I grew in her body and drank milk from her breasts and was cradled and bathed by her. And I’m sure someday my daughter will feel the same alienation. Or perhaps not. Maybe some daughters feel a primordial comfort approaching oneness with their mother’s bodies. I don’t know.

I’ve always had a tendency to warp everyone around me into subject matter, which can insert an analytical distance that makes spontaneous affection feel awkward. Grooming is a way around this. So is caring for sick people. Now that I’m older I have an expanded view of grooming. It’s not something you learn once; it’s a process that changes along with our bodies. Makeup, then, is an adaptive tool and an optimistic act. You make the most of what you’ve got. Doing your makeup (Is this particular diction, “doing” the common vernacular for “applying” makeup?) confirms that what you’ve got is worthy of your attention. By doing my mother’s makeup, I was deciding that despite her “flaws” and mine, the ugly years between us, our relationship was still worthy of attention.

Sometimes our most hidden feelings can only become aesthetic choices; and not poems or art. Mine became both. My mother and I have led very different lives and this has made us strange to each other. That summer, I sat her in a chair to repair. I took part in the ancient salon chair ritual. The art of care. Can an etymologist explain why these words rhyme? I think one gift of age if you do it right is you learn to lovingly integrate things that are indifferent to you—like nature and strangers—as well as all that is unfair. There are times when we must love our mother as a concept, see what’s really there, before we can lay our relationship bare.